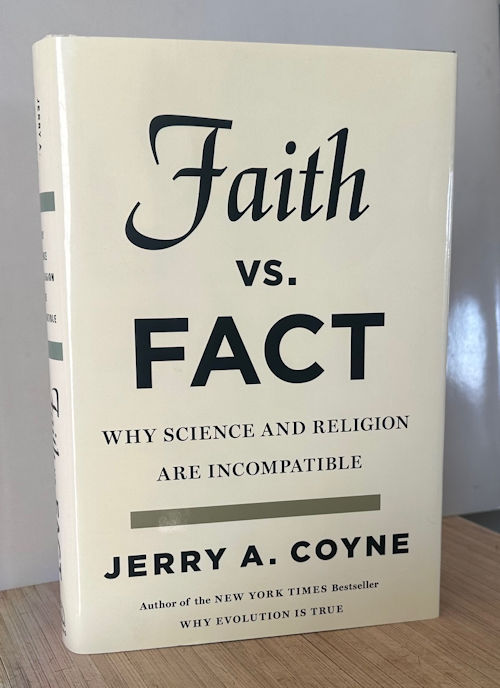

Subtitled “Why Science and Religion are Incompatible”

(Viking, May 2015, xxii + 311pp, including 46pp of acknowledgements, notes, references,and index)

(Earlier: post 1)

Summary: Chapter 2: What’s Incompatible?

This chapter considers science, religion, their incompatibility, and their conflicts of method, outcome, and philosophy.

Science is “a method for understanding how the universe (matter, our bodies and behavior, the cosmos, and so on) actually works.” Scientists are subject to confirmation bias just like everyone else, but the scientific toolset is designed to correct errors. Scientific truth is always provisional, it can change; in a sense scientists can prove a theory wrong, but never right. Still, fields like evolution have so much evidence they are taken as true, especially since it’s easy to imagine evidence that would overturn it (none of which has been found). Science must incorporate falsifiability, and be open to alternative explanations. If something is wrong, it will be found out quickly. That’s why it’s silly to think that evolutionists conspire to prop up a theory they know to be wrong. On the contrary, anyone who did overturn it would gain instant fame. Science requires replication of results; it involves parsimony; it lives with uncertainty. It’s the same everywhere in the world.

Religion is, to choose a common definition: “Action of conduct indicating belief in, obedience to, and reverence for a god, gods, or similar superhuman power; the performance of religious rites or observances.” Characteristics include theism, a moral system, and the idea that God interacts directly with you in a personal relationship. Author considers issues about whether religion looks for truth (it *claims* truth), how most believers believe in a literal (not metaphorical) god; that religions make many empirical claims (but different ones from religion to religion); that many take these claims literally while some (the accommodations) insist some are to be read metaphorically (but how do you tell which ones?); how most people simply reject facts that conflict with their faith; how evolution in particular is a big problem for such people; and how many are religious not for the truth claims but because for them religion is a community (and are in fact quite ignorant of the details of their doctrines).

The incompatibility of science and religion involve their different methods for getting knowledge about reality, their different ways of assessing the reliability of that knowledge; and their different conclusions about the universe.

Conflicts of Method include evidence on the one hand and revelation, authority, and dogma on the other. Science relies on principle of falsifiability, while religion resorts to apologetics. Religion cherry-picks its truths, turns scientific necessities into theological virtues, and fabricates answers to hard or insoluble questions. Religion hijacks the evolved human tendency to be trustworthy when young. Your religion is mostly an accident of your birth. If there is ‘one true religion’, as a matter of chance, it’s likely not yours.

Conflicts of Outcome: why don’t the methods of faith correspond to the results of the methods of science? There seems to be no verified facts about reality that came from scripture or revelation that was later confirmed by science.

Conflict of Philosophy: Science doesn’t presume naturalism; it’s a conclusion arising from the success of science to explain things without resorting to supernatural explanations. If certain supernatural claims were true, e.g. about the efficacy of prayer, science would detect evidence of those effects. It never does. The provisional conclusion of science is that no supernatural powers or entities exist. This is ‘philosophical naturalism.’

Comments

On one level this discussion is obvious and straightforward, if not to the religious (as I alluded to yesterday); but there’s another level that this book and others like it don’t explore. Which involves: *Why* are people attracted to supernatural explanations? About which a book could be written. And second, how, I think, that to a large degree it doesn’t matter to most people so much what’s **true** about the universe, as that one shares a philosophy and a submission to a particular doctrine with one’s family and community – as a bolster against other tribes.

Raw Notes. There are lots of good bits from these 70 pages of the book that my summary above doesn’t do justice to.

\

Ch2, What’s Incompatible?

Quote from Natalie Angier about the Ph.D. who wrestles powerpoints by day and reads internally contradictory holy books by night and think both are convincing.

How author learned about science: by being thrust into Harvard where everyone argued, trying to pick holes in every argument, finding problems. Not personal attacks, but a kind of quality control…

What Is Science?

Not just an activity, or a set of provisional facts. Science is “a method for understanding how the universe (matter, our bodies and behavior, the cosmos, and so on) actually works.” (p28.7) A set of tools.

Feynman: The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool. P28b

Scientists like everyone else are subject to confirmation bias.

Author equates truth and fact (p29b); scientific truth isn’t absolute, but can change. Big examples: geocentrism, N rays.

In a sense scientists can prove a theory wrong, but never right. Still fields like evolution have so much evidence they are taken as true, especially since it’s easy to imagine evidence that would overturn it (none of which has been found).

What are the components of the scientific toolkit? The common one is ‘hypothesis, test, confirm’. But it’s not always like that. You have to gather facts before you can form a hypothesis. And some topics don’t allow tests, but observations—cosmology. And along with predictions, theories can make ‘retrodictions’, making sense of previously known facts. And science is quantitative.

And science incorporates the idea of falsifiability; there must always be a way of showing a theory to be wrong. While the faithful make up excuses for, e.g. ‘God will not be tested.’

Scientists also ask, are the alternative explanations? Could something have gone wrong? If there is, it will be found out quickly. This is why it’s silly to think that evolutionists conspire to prop up a theory they know to be wrong. On the contrary, anyone who did overturn it would gain instant fame… p35

Science also involves replication of results.

And science entails parsimony, the idea that the simplest explanation for something is usually best.

And science lives with uncertainty. We don’t know how life began. Scientists live with it; Feynman quote p38.

There is also the international character of science, its collectivity. Science is the same everywhere in the world. (The Bible has a scientific test about which god is real, Baal or Yahweh, p39m).

Broadly speaking science is any endeavor that uses the tools of reason, observation, and experiment, including historians, biblical scholars, car mechanics. Story about Stephen Jay Gould encountering a plumber, p40-41, using logical means to find a leak in a very scientific manner, but also claiming to be a staunch creationist.

What Is Religion?

There are many definitions, but author chooses a common one that corresponds to the three Abrahamic faiths: “Action of conduct indicating belief in, obedience to, and reverence for a god, gods, or similar superhuman power; the performance of religious rites or observances.”

Three characteristics: theism, that god interacts with the world; embrace of a moral system (laid out for obedience by that god); and the idea that God interacts directly with you in a personal relationship. We’ll focus on the empirical claims made by religions, whether they are the claims of the church, of theologians, or of regular believers.

Does religion look for truth?

It seems obvious that religion assumes the existence of God; but some theologians minimize this, claiming religion is more about morals or building a community. Examples of Francis Spufford and Reza Aslan (p44t), who reduce holy books to collections of metaphors – in contrast of course to the vast majority of ordinary believers.

In contrast, the Bible makes empirical claims about god – examples with comments from Richard Swinburne and Mikael Stenmark. And John Polkinghorne, who emphasized the need for an empirical grounding of faith. Ian Barbour. Francis Collins.

Existence Claims: Is There a God?

Belief in gods is universal and strong. Surveys—93% in Indonesia, 4% in Japan. In the US, 70%. Most of these believe in an involved and intervening god. Many are quite literal. More intellectual believers have more nebulous and impersonal descriptions – Richard Swinburne, Alvin Plantinga – a spirit or force about whom we can say little. But most believers are very specific about his attributes.

Other Empirical Claims of Religion

Long list from the Nicene Creed of specific claims. A monotheistic God, but in three parts; the creation of the universe; his son, born of a virgin, sacrificed to redeem believers from sin, and so on. Heaven and hell.

Of course these conflict with the claims of other faiths – Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, who don’t recognize Jesus as the Messiah. Etc etc.

Again, polls show literalism of these claims is widespread. P51. Especially in the US, but in Britain too – Julian Baggini thought otherwise, did his own poll, and changed his mind. P52. Muslims are especially pious and literalistic – about God and Muhammad, about how the Quran should be read literally, word for word, p53m.

Accommodationists typically attribute religious violence as due to politics or social dysfunction, an idea which simply extends the claim that religions don’t involve truth claims about the universe. Pinker vs Wieseltier.

Is Scripture Literal or Allegorical?

A recurrent theme is theology is that as science has disproved scriptural claims, these claims have morphed into being mere allegories. Liberal believers say things like, the Bible is not a textbook of science. Some claim the idea of literalism is a recent phenomenon. Andrew Sullivan, claiming that no one with a brain can think the story of Adam and Eve is meant literally. Yet Catholicism has insisted on it. Other references of same. Aquinas discussing Saint Augustine. Augustine was a literalist about many things since refuted by science: the young earth, creation, Noah and his Ark.

And if you do claim that certain parts of the Bible are to be read metaphorically – how do you tell which parts are metaphorical and which are meant to be real? “This is particularly difficult for Christians, because the historical evidence for Jesus—that is, for a real person around whom the myth accreted—is thin. And evidence for Jesus as the son of God is unconvincing, resting solely on the assertions of the Bible and interpretations of people writing decades after the events described in the Gospels.” P59t

And most people, according to surveys, would simply reject facts if they conflicted with their faith.

Evolution: The Biggest Problem

The clearest example of religion’s resistance to science is evolution—which has implications that “are distressing to many believers”. Polls show evolution is rejected by believers. “Yet when it comes to evolution, many Americans remain in the Bronze Age.” P60.2 It’s not an artifact of ignorance of evidence – look at all the science popularizers like Dawkins, Sagan, etc etc. Americans deny evolution because of religion. Many religious people say things like “Nothing could make me give up my beliefs.”

Can You Have Faith Without Truth Claims?

Many, maybe most, people are religious not because of arguments about God and scripture, but because for them religion is a community, about feelings and emotions. Surveys have shown many religious people are in fact quite ignorant of the details of their doctrines. (p61b). Jonathan Haidt sees religious communality as primary.

But would they remain religious if claims about Jesus or Joseph Smith were undermined? We do know that many who abandon religion do so because of losing belief in its doctrines. P62m.

Theologians downplay empirical claims – except when talking to ‘regular’ believers. Example Alvin Plantinga.

The Incompatibility

Not logical, or practical; rather, “mutually intolerant” p64m. Author claims science and religion are *in*compatible because they have 1) different methods for getting knowledge about reality; 2) different ways of assessing the reliability of that knowledge; and 3) arrive at different conclusions about the universe.

Religious ‘knowledge’ not only conflicts with scientific knowledge, but also knowledge from other religions.

Gould’s idea they are complementary fails on two counts.

Issues of methodology can be summarized by asking “How would I know if I was wrong?”

Conflicts of Method

Science relies on evidence, and can imagine evidence that would prove a truth wrong; religion relies of revelation, authority, and dogma. Some religious claims are untestable because they occurred in the past, but science can point out the absence of evidence for such claims. Religion relies on confirmation bias, starting with one was taught in childhood, then accepting only those facts that support those prejudices. ‘Apologetics’ work to defend religion against counter-arguments.

Faith

Faith is the confident belief in something for which there is insufficient evidence to persuade all reasonable people of that belief. Also dictionary definition p67m Faith is routinely regarded as a virtue; doubting Thomas. Fideism is the idea that faith is hostile to reason. It is taken as a virtue to have faith in things that are absurd. Even today, the Pope denigrates curiosity. Martin Luther said reason was the enemy of faith. Believers sometimes accuse scientists of having ‘faith’, as if this makes both just as bad as the other; more on this in chapter 4.

Authority as the Arbiter of Truth

Church dogmas or theologians are the arbiters of religious truth; science has no equivalents. No texts or scientists are regarded as inerrant. They have confidence in some authorities, because they have earned that trust.

Some religious dogma has been settled *by vote* over the centuries – examples among Catholics p71. Such changes don’t come from new information, but from secular currents in society. Hell is now seen as ‘separation from God’, not an underground barbecue. Mormons changed their policy on blacks.

Falsifiability.

Religion would welcome evidence if it validated their claims; but when evidence doesn’t support their claims, they usually result to apologetics. E.g. resurrection of Jesus; William Lane Craig states that nothing could shake his belief. Justin Thacker. These statements are irrational. Karl Giberson, about how some claims are unfalsifiable. Needless to say, this is not how science works.

Cherry-picking your truths from scripture or authority

Critics of atheists claim that the Bible isn’t a book of science. Yet many believers think the Bible does give us facts. But to think parts of the Bible are mere parable begs the question of how to decide which parts are which; by implication, the literalists are more intellectually honest. We can’t know what the Bible’s authors meant when they wrote it; most of it reads as if relating literal truths. That’s how many people read it, and Quran. Any story in the Bible can be literal or a metaphor; take your pick. In practice, the things that science has falsified tend to become metaphors…

Turning Scientific Necessities into Theological Virtues

Some apologists will claim theology is made better once science has ‘corrected’ parts of scripture. Evolution makes life so much more interesting!

Fabricating Answers to Hard or Insoluble Questions

Why is God hidden? They have answers for that too, though they make little sense and depend on wordplay. Some simply reject the need for evidence. Immortality? Natural evil.

Applying Different Standards…

Truth claims of Scientology, Mormonism, Christian Science. Most believers reject these, but only because these three religions are fairly new. People don’t react to their own religions the same way because they were indoctrinated through family and friends. “Religion has hijacked the evolved tendency…” p83.8 Your religion is mostly an accident of your birth, and as an adult you have are emotionally invested in its truth, and so subject to confirmation bias.

More examples of various religious claims. There are a dozen ‘major’ religions, but thousands of branches. Religions are just incompatible with science, they’re incompatible with each other.

There might be one true religion, but as a matter of chance, it’s likely not yours. Don’t you care if you’re following the right one? John Loftus and the ‘outside test for faith’ p86t. [[ Comment I had here moved above in this post. ]]

The various scientific disciplines share the same form and toolkit of science.

Scientific Truth is Progressive and Cumulative; Theological ‘Truth’ Isn’t.

Scientific progress is apparent and common across the world. Theology changes, but doesn’t advance. Hell is reconfigured as ‘separation from God’. The C Church eliminates its list of banned books. And morality advanced, as society advances.

But religion hasn’t come any closer to understanding the divine; whether gods exist; whether there is one or many, and so on. There are fundamentalists and apophatic theologians…. Changes in theology are driven by science or changes in secular culture. Religious morality is usually one step behind secular morality (p88.7)

Yet there are apologists who claim all this as a virtue; that theology hasn’t changed means it’s reached its goal of perceiving truth better than science has – J.P. Moreland, p89m.

Conflicts of Outcome

If the methods of faith were reliable, the results should correspond to the results of the methods of science. But they don’t. Disproved claims of religion include many scientific claims, as well as historic claims (no evidence for the exodus of Israelites from Egypt, or of the miracles surrounding the Resurrection).

If such ‘natural truths’ cannot be verified, why credit the harder-to-test ‘divine truths’?

Author has challenged anyone to give him a single verified fact about reality that came from scripture or revelation that was later confirmed by science.

Conflicts of Philosophy

The issue is whether gods are even a realistic possibility.

Naturalism is not a premise of science; it’s a conclusion arising from the success of science to explain things without resorting to supernatural explanations.

In fact, scientists like Newton did invoke supernatural explanations, e.g. God. It was later scientists who developed explanations that did not require those – famous anecdote about Laplace p92.

There are some who claim science can *only* be about what is not supernatural – Lewontin p93t – but in principle science is open the confirming supernatural events, e.g. studies about the efficacy of prayer (or of ESP, etc.). There *could* be evidence from such studies – but there is not. Thus the provisional conclusion of science is that supernatural powers or entities do not exist; an attitude called ‘philosophical naturalism’. [provisional: see 95b]