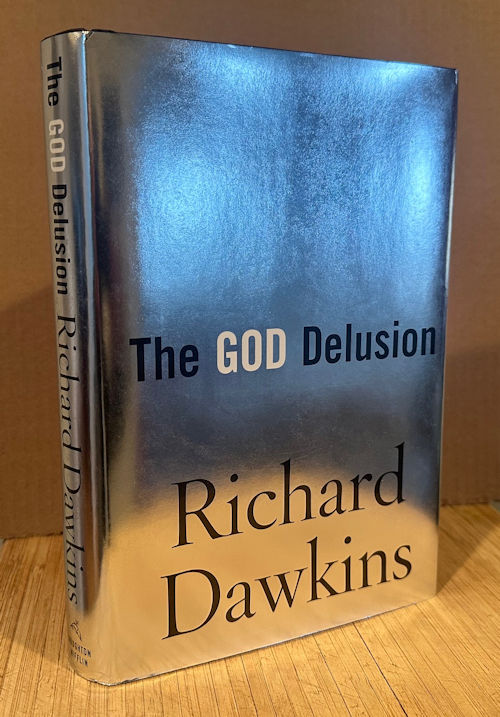

(Houghton Mifflin, Oct. 2006, 406pp, including 26pp of appendix, books cited, notes, and index)

(Post 1; Post 2; Post 3; Post 4)

*

Here are notes on the final four chapters. Glosses follow in the next post.

*

Ch 7, The ‘Good’ Book and the Changing Moral Zeitgeist, p235

So are scriptures the source of morals? They might be so directly, via rules like the Ten Commandments, or indirectly, by setting examples. Either way, the Bible is just weird, as would be expected of a “cobbled-together anthology of disjointed documents…” (p237). That zealots hold it up as the source of morals indicates they haven’t read it, or don’t understand it.

P237, The Old Testament. Noah—God was so upset with humanity he drowned the lot of them, except for one family. Such stories aren’t taken literally anymore? But that’s the point [[ Pinker makes this point too, in ANGELS ]] —if we pick and choose which stories to take literally, then scripture isn’t the basis for what we believe is moral. Anyway many *do* take it literally, just as some believe the recent tsunami was the result of particular sins. They consider innocent victims of such disasters to be collateral damage. “You’d think an omnipotent god would have a more targeted approach…”

In the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, the men of Sodom demand access to male angels so they can sodomize them—and Lot turns over his daughters to them instead. What morality is that? Later Lot’s wife is turned into a pillar of salt—for looking back. Then Lot’s daughters get him drunk to have sex with him. Similar odd and gruesome stories come in Judges. Abraham, founder of the three great religions, passed his wife off as his sister, who then became part of the pharaoh’s harem. Later he was perfectly prepared to sacrifice his son. If not literal, what metaphorical messages are these stories supposed to convey? What kind of God would require Jephthah to sacrifice his daughter?

God’s rage over rival gods resembles sexual jealousy of the worst kind. (And why were people of that era so ready to cheat?) A golden calf was sin enough for a slaughter and plague. Later God incited Moses into slaughtering the Midianites—except for the virgin women, to keep for his own tribe. For some reason, Baal was a favorite among rival gods.

Again, you can’t claim the Bible as the source of morality—there’s some extra unspoken criteria for deciding which parts are ‘symbolic’ and which are literal. Have biblical advocates actually read it? See Leviticus 20 for a gruesome list of what the Bible actually says merits the death penalty (p248). The 10 commandments apparently rank the gravest sins as worshipping the wrong gods and making graven images. The famous Weinberg quote 249.7

P250, Is the New Testament any better?. So what about the NT? Is it any better? Jesus was certainly an improvement—but that’s the point: he didn’t derive *his* morals from scripture. Plus, his family values were dodgy.

Some teachings are no better than in the OT: the doctrine of ‘atonement’ for original sin, which condemns everyone for the sins of remote ancestors. And it adds a gruesome sado-masochism: that God incarnated himself as a man in order to be tortured and killed, in this ‘atonement’, including for all future sins! Why couldn’t God simply forgive our sins, without all the torture? And condemning Jews to be forever known as ‘Jesus-killers’? It’s all barking mad, relying on a Jewish doctrine of blood for atonement. Who was god trying to impress?

Another unpalatable aspect of the NT is that teachings such as ‘love thy neighbor’ applied only to the in-group—i.e. other Jews. [[ Again, as long understood. ]]

P254, Love Thy Neighbour. As an example with Southern Baptists counting the number of Alabamans in Hell—including of course everyone not in a church congregation—people always assume that they themselves will be among the ‘saved’; rapture sites are further examples. John Hartung has shown that Biblical injunction not to kill etc applied only to other Jews; there’s no proscription against killing ‘heathen’. Hartung presented a story to Israeli schoolchildren, who remarkably supported a massacre on the grounds that Arabs were ‘unclean’ or that God had promised them the land. But change the story to some ‘General Lin’ in a remote Chinese kingdom, and the reaction reverses. I.e., religion justifies things we wouldn’t otherwise condone. Hartung shows that Jesus supported the same ‘in-group’ morality as in the OT. It’s no different than attitudes of other ancient works, except the Bible is still accepted as a guide to morality. (258m)

Similar attitudes appear in hymns or prayers thanking God for not making one a heathen, or a woman.

In practice religious conflicts aren’t over religion per se, but are defined by the labels used for each side—Protestants vs Catholics, etc.; the same in India (Salman Rushie quote). The in/out-grouping is similar to the way football fans separate themselves, except that religion 1) labels children, 2) segregates schools, and 3) has taboos against ‘marrying out’. ‘Mixed marriages’ are frequently regarded in shame. Studies show in-group marriage is common among Christians, but especially so among Jews, whose rabbis often refuse to officiate over ‘mixed’ marriages.

P262, The Moral Zeitgeist. Then where do we get our ideas of right and wrong? Except for groups like the Taliban and the American Christian equivalent, most people, religious or not, subscribe to the same set of vaguely liberal principles—don’t hurt others, freedom of speech, paying taxes, etc. Examples of ‘New Ten Commandments’ (p263, source in footnote 103) show various attempts to capture such values; author would include things about indoctrinating children and valuing a timescale longer than your own. (Author mentions many such examples can be found, just google ‘new ten commandments’.)

The world has moved on since biblical times—slavery was abolished in the 19th century, women have the right to vote almost universally, though it was widely denied as late as 1920. Racism was common until the early 20th century, blacks and other ‘unwashed’ assumed to be inferior to whites. Even Thomas Huxley and Abraham Lincoln did not believe in ‘equality’ of the races. The Zeitgeist moves on. Our attitudes about animals have changed—at one time dodos were killed merely for sport, as was ‘game’ in Africa. The way attitudes about racy books—not to mention that women or servants might read them too. Attitudes about the Iraq war show diminishing approval for warlike actions. Even the evil of Hitler is modest by the standards of the ancients. Derogatory terms for racial groups are no longer commonly used, nor would scholars typify entire groups. Even H.G. Wells wondered what to do with the ‘inferior’ races.

So why has this change occurred? Not because of religion; in spite of it. [[ I would suggest it’s simply the greater interconnectivity of the world, both physically and virtually—no one grows up experiencing only their own little tribe. We grow up more knowledgeable and enlightened. This trend is ultimately what ‘liberal’ means, and why ‘conservatives’ tend to be 50 years behind the times – even though they’d seem shockingly progressive by the times of 100 years ago. ]] It happens gradually, through personal connections and editorials and new laws. It’s not steady but jagged (note jibe at US government in early 2000s, p271). Charismatic leaders play a role. Education—especially biological science, to overcome the idea that women and other races weren’t ‘fully human’. Beyond that author will not speculate—but the zeitgeist does move, and not because of religion. [[ At the same time—taking a page from sf stories of post-apocalypse—I suspect that a global catastrophe would certainly destroy this progressive zeitgeist and restore the biases and prejudices of human nature, back on the tribal level. There’s no entirely escaping the legacy of our evolutionary past. ]]

P272, What about Hitler and Stalin? Weren’t They Atheists?. Both clearly were evil men, but people who ask this presume that they were evil *because* they were atheists (which is dubious in Hitler’s case), which doesn’t follow at all. What matters is, does atheism systematically influence people to do bad things? There’s no evidence of this.

Stalin was atheist, and derided religion; Hitler never renounced his upbringing in the Catholic church, and statements later in life indicate a nominal belief. He alluded to the Jewish blame for death on the cross; he gave speeches about his duty as a Christian. OTOH he made virulently anti-Christian statements in his Table Talk. Or maybe Hitler was just opportunistic and cynical. In any event all the evil carried out in his name was done by soldiers, et al, who presumably were Christian. Hitler never stopped speaking of ‘providence’ (and the ‘will of God’ p277).

In any event, no one ever fought a war over atheism. Sam Harris quote.

Ch 8, What’s Wrong with Religion? Why Be So Hostile? p279

(Opens with George Carlin quote)

Author doesn’t engage in confrontation; formal debates are not a way to get at the truth (as example description suggests). Still, author has gained a reputation for pugnacity; even friends who agree with him wonder why be so hostile, just dismiss it like astrology and crystal energy.

Well, such ‘hostility’ is limited to words, not wars (the author isn’t about to bomb anybody). And it doesn’t mean author is a ‘fundamentalist’ atheist, analogous to being a Bible Belt fundamentalist.

P282, Fundamentalism and the Subversion of Science. The difference is that the religious fundamentalist believes in the truth of a holy book, and evidence to the contrary must be thrown out. A scientist believes a book because of the evidence it presents, and when evidence changes, the books change.

But isn’t belief in evidence a kind of fundamentalist faith? No more so in science than anything else. We don’t dismiss evidence in a murder trial by philosophical evasion or relativistic pleas. Nor is author’s passion for evolution a kind of fundamentalism—it’s an enthusiasm, and a frustration that others don’t see it or won’t because of their holy books. Scientists do change their beliefs when evidence changes—example of belief about Golgi apparatus.

And author is hostile to religion because it subverts science—it says not to change your minds. A sad example is geologist Kurt Wise (at Bryan College in TN), who agonized over the conflict between science and his religious upbringing until he abruptly decided to give up the former. He explicitly rejects evidence because the Bible requires a young earth. It is like 1984, 2+2=5.

P286, The Dark Side of Absolutism. Despite the optimistic idea that the zeitgeist is changing (see previous chapter) there are many who don’t accept it, who are still absolutist, e.g. as in Pakistan and Afghanistan where people can be sentenced to death for insulting the prophet or converting away from Islam. The constitution of the ‘liberal’ Afghanistan still contains that penalty. Examples p287.

Blasphemy laws still exist in Britain. And in the US websites depict the ‘American Taliban’ with extremist quotes from Ann Coulter et al, p288.

P289, Faith and Homosexuality. The Taliban executes homosexuals, and even Britain had laws against homosexuality as late as 1967. Alan Turing committed suicide…

Similarly the ‘American Taliban’ includes Jesse Helms, Pat Robertson, Fred Phelps, et al, who denounce homosexuals and forbid their rights once the Christian majority ‘takes control’… as always faith-based moralizers care passionately about what other people do or think even in private.

P291, Faith and the Sanctity of Human Life. Typically the religious faithful consider embryos fully human and therefore abortion is murder. Oddly, many are less concerned about taking adult life—i.e. the death penalty, highest since 1976 in Texas, home state of GW Bush, who once (according to a report by Tucker Carlson) mocked a death row inmate pleading for her life. Mother Teresa said the greatest destroyer of peace is abortion(!). And Randall Terry pledges to execute abortion providers, and to conquer the country for the 10 commandments. This is Christian fascism.

A utilitarian view might focus on relative suffering, but slippery-slope arguments can be applied to abortion, and to euthanasia—if you allow certain cases, you invite erosion of standards until absurd cases are allowed—and justify absolutist stands that way. But religious foes of abortion don’t bother; an embryo is a person, that’s that. Despite inconsistency with standards for in vitro fertilization…

Fanatics can’t distinguish between killing a handful of cells and killing a full-grown abortion doctor, and proudly target the latter with high-minded moral purpose. In an interview one such defended his actions by dismissing laws as simply ‘made-up’ by men; like Muslim militants, who claim allegiance only to holy law. Another, Paul Hill, was executed in 2003 for one such crime, predicting he would become a martyr. Some called him a psychopath; author doesn’t think so, just poisoned by religious faith. By non-absolutist standards, great suffering was brought about by the killing of the doctor, whereas suffering of an embryo is nonexistent or disputable (e.g. no more than an embryonic cow or lamb). Non-absolutists would be more concerned about relative suffering, or what constitutes a human, or whether an embryo can suffer.

P298, The Great Beethoven Fallacy. But isn’t the point the *potential* of the embryo? A frequent anecdote is about a pregnant mother with four (or nine) previous children, many of whom were blind or deaf, whose father had syphilis, etc.—if her child were aborted, it would have murdered Beethoven.

The anecdote isn’t even true—it’s an inflated urban legend—but is fallacious anyway. One might as well have murdered Beethoven by refusing to have intercourse in the first place. What about the abortion that could have murdered Hitler? But 43 religious sites quote the anecdote, none noticing the fallacy. Every sperm is sacred, as Monty Python sang. Anyway the presumption is that only *human* life counts, when, given evolution, it’s impossible to draw any firm line between ourselves and other animals.

P301, How ‘Moderation’ in Faith Fosters Fanaticism. Other absolutists include the theocracies of Saudi Arabia, which oppress women, or the American ‘rapture’ Christians who seem to *want* a nuclear holocaust in order to bring on the Second Coming. (The changing moral zeitgeist of the previous chapter has left them by.) But even ‘moderates’ promote the climate in which such extremists flourish. The 2005 London bombings are explained only by religious faith; they and Osama bin Laden *actually believe* what they say (quoting Sam Harris again). But reports and governments sidestep this point, blaming politics or ‘terror’ or ‘evil’. But the ‘terrorists’ aren’t psychotic; they perceive themselves righteous. A NYr article quotes a Palestinian terrorist about his eagerness to become a martyr (long quote). They have no doubts; they really believe it.

Bertrand Russell quote 306: “Many people would sooner die than think. In fact they do.”

If religious faith is to be respected per se, why not respect Osama bin Laden’s? This is why author warns against faith of any kind, not just extremist faith. Religious leaders apologize for extremist ‘perversion’ of faith, but what is the standard for faith in the first place?

Moderate Islam is a myth; some pick and choose from the Koran to justify what they want, or use the latest verses, but the peaceful verses are near the beginning.

What’s especially pernicious in any religion is teaching children that faith is a virtue….

Ch 9, Childhood, Abuse, and the Escape from Religion,

In 1858 a Jewish child was seized from his parents by officials in Bologna, Italy, and put into custody of the state to be raised as a Catholic—all because a Catholic nursemaid had once ‘baptized’ the child, who thus was considered by religious standards to *be* Catholic. The church allows anyone to baptize anyone (p312)—it just takes water and a few words.

To the religious mind, such a ritual takes precedence over any ordinary considerations, e.g. parental concern. Further, church officials in such cases sincerely believe they’re doing the right thing. (It’s obvious to them their religion is superior to any other.) And third, religious people just know, without evidence, that the religion of their birth is the one true religion, and all others are in error. Martyrs would rather die than convert (even the Jewish child’s parents declined to be baptized if only to retrieve their son). Fourth, it’s presumptuous to think that a child can have any religious belief at all, at that age; yet this presumption is unquestioned even today.

P315, Physical and Mental Abuse. This isn’t about sexual abuse, though we do live in a time of hysteria over pedophilia… despite evident cases of manufactured memories, etc., cases such as the Christian Brothers and the nuns in Irish girls’ schools. Author would suggest that bad as those are, it’s not as bad as the psychological damage caused by being raised in the church. Being molested can be icky, believing in hell can be traumatizing.

Unfortunately what’s mainstream in the US often seems extreme to the rest of the world—never mind those who really want to turn America into a Christian theocracy. (As in the Left Behind computer game.) One church leader creates ‘Hell Houses’ to scare kids about what might happen to them after they die, the optimum age for attendance being 12. Of course, church leaders always believe they will be among the saved. Note that Dawkins did a TV documentary in Britain, The Root of All Evil, after which some viewers contacted him about pursuing counseling. Some tell of the trauma of what they believed, and the difficulty in giving up a community and family along with a belief system, or relationships that break up. Example Jill Mytton, p322, and what she was told to believe about hellfire and damnation. Julia Sweeney ends her play “Letting Go of God” with that realization, and the reactions of her parents. Even some priests (e.g. Dan Barker) give up belief but are unable to tell anyone, caught up in social and professional obligations…

P325, In Defence of Children. Nicholas Humphrey argued an exception to freedom of speech—children have a right not to have their minds addled with nonsense. Yet, who decides what’s nonsense? Author thinks it’s more important to teach how to think, than what to think. Example of Inca girl sent as a sacrifice; should we revel in her experience because her culture believed in her sacrifice? Shouldn’t we defer to standards of the time? Author thinks we *can* blame the elders for foisting such beliefs on an innocent girl. What about female circumcision? An allowable cultural practice? Yet no adult woman who missed it volunteers later in life…

How about allowing the Amish to raise children their own way? Cf Humphrey on cultural diversity, 329m. The price of maintaining such cultural diversity and practices is…the lives of children. Shouldn’t children have something to say in the matter? A Supreme Court decision in 1972 favored parents who wanted to remove their children from school—in the name of preserving the Amish community and religion (and avoiding modernity). In contrast, adults don’t volunteer to become Amish, and the children had no practical choice. It’s condescending to allow it… see 331t

P331, An Educational Scandal. In Britain the funding of a school that taught biblical creationism was justified (by Tony Blair) on the grounds of ‘diversity’. The head of that church, like others, made various scientifically illiterate remarks. A lecture on a UK website about teaching biblical science—removed but cached and later refound—proudly endorses the Bible as the source of scientific knowledge—and it’s by a science teacher. Protests, endorsed by scientists and theologians, were dismissed by the government. In a later radio interview, the school seemed unaware of what that science teacher had actually endorsed…

P337, Consciousness-Raising Again. Author cites newspaper photo in which children of various faiths portrayed the nativity scene as grotesque. The ‘brights’ explicitly insist that children must make their own decision to join or not. Shouldn’t all faiths do the same? Author would like to ‘consciousness-raise’ by not calling children after their parents’ religions—anymore than children are called liberal or conservative.

A case could be made to teach comparative religion—children would become aware they are mutually incompatible. Of course the faithful are uncomfortable with pointing this out, because it undermines their position about their own religion’s superiority.

P340, Religious Education as Part of Literary Culture. It’s remarkable as far back as 1954 how ignorant many Christians and Catholics are about their own Bible. The English Bible *should* be taught as literature, just like the Greek and Roman myths. P341 a list of phrases from the Bible (two pages worth!). PG Wodehouse, Shakespeare, presumably literature of other languages, rely on allusions to holy books. They can still be appreciated without believing in supernatural beliefs.

Ch 10, A Much Needed Gap?, p345

Title refers to jest “this book fills a much needed gap” – a solecism, but at times repeated seriously. So, does religion fill such a gap? Is there a god-shaped gap in the brain?

Religion has been thought to fill four roles in human life: explanation, exhortation, consolation, and inspiration. This chapter deals with the latter two.

P347, Binker. Binker is the imaginary friend of Christopher Robin – long quote from AA Milne. Author didn’t have one, but apparently many children do have ‘imaginary friends’ they really do believe exist. Perhaps this is a basis for understanding theistic belief in adults? Another story about a girl’s ‘little purple man’ who gave her advice on her career…. Has religion evolved as a gradual postponement of the age when children give up their Binkers?

Or the reverse? Julian Jayne’s bicameral mind. Evelyn Waugh. The ‘second voice’ was really inside their heads. Are gods the result of Binkers, or vice versa? Perhaps both result from the same psychological predisposition.

P352, Consolation. Must acknowledge the role of consolation; if you remove God, what’s in its place? Of course, religion’s power to console doesn’t make it true, even if it were demonstrably necessary to human psychological well-being. Yet some resent attacks on faith anyway. Maybe truth is less important than human feelings. Dennett distinguishes between ‘belief’ and ‘belief in belief’.

Still, author does not concede premise—i.e., there’s no evidence atheists are more depressed than the faithful. What are claims of religion to offer consolation? There is consolation through direct physical contact, and also consolation through new information or perspectives, e.g. the idea that by the time an old man is ready to die, the child he once was already died long ago, by growing up, 354.2. (Thus, reasons not to fear death.) Many people do claim consolation after physical disasters, or in the face of terminal illness. But of course, false beliefs (e.g. in a cure) can be just as consoling.

If 95% of people really believe they’ll survive after death, shouldn’t they be looking forward to it? Why do friends weep? Why opposition to assisted suicide, etc.? Perhaps religious people don’t *really* believe in life after death. Or perhaps they fear merely the process of dying—since unlike animals, humans are not allowed to be anesthetized to death. And it’s the religious who oppose assisted suicide, etc., while atheists support it…

Oddly, according to one nurse’s report, it’s the religious who most fear dying—which sort of contradicts the premise of consolation. The Catholic church has its ‘purgatory’, a sort of Ellis Island waiting room, for which ‘indulgences’ were once sold by the church in a scam rivaling any; later various schemes of prayer served the equivalent, as at the New College of Oxford…

(359b) Author fascinated by the ‘evidence’ of purgatory—simply that since we pray for the dead, it must exist, or the praying would make no sense.

This mirrors the common claim for consolation—if there were no God, life would be pointless, etc. Therefore. Well, maybe life *is* pointless. Circular reasoning. And presumptuous to believe that something, e.g. God, must exist merely to provide *you* with meaning. An infantile attitude, like looking for someone to blame every time one gets hurt. (“There is something infantile…” 360.6)

The adult view is that life is as meaningful as we make it.

P360, Inspiration. This is a matter of personal taste, perhaps, so the argument is rhetorical rather than logical. We should feel lucky to be alive at this moment in time, considering all the possible people who could be alive; that we are makes life precious; it’s an insult to think it dull or boring. (Q 361m) How to fill the gap? Science is one way—the ability of our minds, shaped by evolution for basic survival, to create a much greater model of the world, results including art and science. One final picture…

The Mother of All Burkas. A burka is the sack-like garment enclosing a woman except for a slit to see through. A sad sight. The light we see with our eyes ranges over a spectrum that, on the scale of an inch-wide slit, leaves out miles and miles of wavelengths that we can’t perceive. Science widens that window. Telescopes and cameras reveal more of the spectrum. Our imaginations fail trying to understand things outside a range of sizes—thus quantum ranges are a mystery to us, as are speeds approaching light. Common sense lets us down. Thus Haldane’s remark about the universe being queerer than we *can* imagine. Douglas Adams and others played up this strangeness for laughs. Quantum theory seems as ‘true’ as anything we know, but it’s really weird. Both the ‘many worlds’ interpretation and the ‘Copenhagen’ interpretation (the cat isn’t alive *or* dead until you look) seem contrary to human intuition. (cf Deutsch 365m) Science in general violates common sense—e.g. elementary probabilities… Science *can* be explained; nevertheless, our existence is somehow surprising. What would the world look like if it were revolving? (367m)

Our brains evolved in this ‘Middle World’, which is why only experiences in this range seem intuitive. ‘Solid’ in this range isn’t really solid at the molecular scale. Why can’t General Stumblebine walk through the wall? We even find Galileo’s simple experiments non-intuitive—because we don’t live in a vacuum. We tend to think matter is more ‘real’ than electromagnetic waves. A person is more like a wave—the child you remember had none of the atoms that make you up now. ‘Reality’ depends on what the brain needs to survive. What we experience is just a model of the world, appropriate to the way we live in it. Monkeys experience a 3-d world of tree branches; a water boatman, a 2-d world of the water surface. Bats and swallows would have similar models, despite variations in senses used (echoes vs light). Dogs sense different fatty acids that are different molecular lengths. Colours are perceptions independent of wavelengths. Science opens the window. There may be no limits to understanding.

*