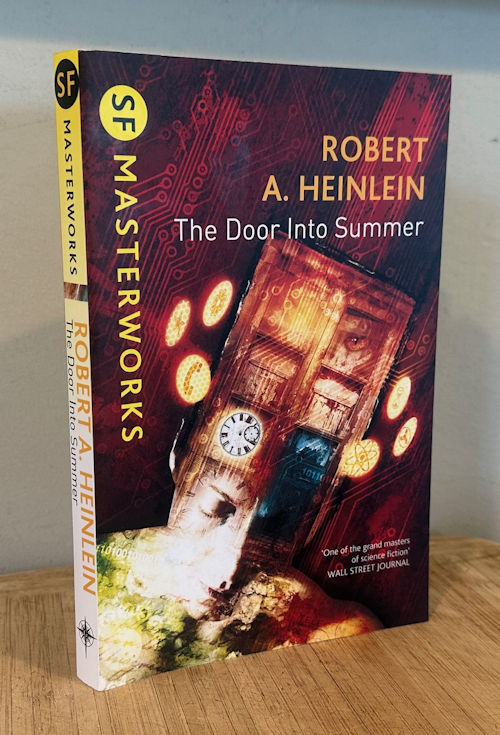

(First published 1957. Edition here: Orion/Gollancz/SF Masterworks 2003, 178pp, with an introduction by Stephen Baxter)

I’m no expert on Robert A. Heinlein — I still haven’t read Farah Mendlesohn’s book about him — but I have read *almost* all his books at least once (excepting one or two at the very end), and over the past decade have been working my way back through the bulk of them for a second (or third) time.

I tend to think of the 30 or so novels in four groups. The early novellas and novels were mostly part of his “Future History” sequence that also included at least half (I think) of his short fiction. That’s 1940s and early 1950s. Second are the dozen “juveniles” published one a year beginning 1947, with a couple later ones some readers do not consider part of this group. Third are the ambitious books like STARSHIP TROOPERS (which some consider a juvenile) and STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND and THE MOON IS A HARSH MISTRESS and maybe TIME ENOUGH FOR LOVE, and then the increasingly self-indulgent books that followed. And not quite fitting any of these groups are three singletons published in the 1950s: THE PUPPET MASTERS, an alien invasion story; DOUBLE STAR, a political story that’s arguably barely science fiction; and this one, THE DOOR INTO SUMMER, a time travel romp about household robots, friendship and betrayal, and a cat named Pete.

The book was famously inspired by one of Heinlein’s own cats, when he lived in Colorado. During the winter this cat would want out, but rejected any door leading to the snow outside. It would check another door, and another.

The book begins in 1970 — 13 years in this book’s future — as an inventor of household robots named Dan Davis, for Daniel Boone Davis, contemplates revenge against two people he thought were friends and investors but who have in fact cheated him out of his business. And/or, escape into the future, via suspended animation, to a time when he could live off his investments. He tries the former and gets shanghaied into the latter, losing his cat Pete, and waking up in 2000 — 43 years in the book’s future — in a changed Los Angeles. He has new technology to learn. His old company, Hired Girl, is still in business, and he gets a job there. He finds out what happened to the couple who cheated him, and also to a young girl he knew (in a fatherly way, ahem) back in 1970.

How to fix everything? (Spoilers.) Why, time travel! A secret even in 2000. But Dan tracks down the inventor of time travel and essentially tricks him into a demonstration using himself — in order to go back to 1970, where he tracks down the girl, manages to rescue his cat, and… well there are a couple final twists.

\

This is the sort of book where you can sense the author making it up as he went along. Heinlein indulges in some fun speculation, mostly about household robots, the product of Dan’s lone genius style brilliance. Imagining how robots actually work is hand-wavey; where Asimov resorted to “positronics” (his invented counterpart to electronics), Heinlein alludes to “Thorsen memory tubes,” one tube for each task a robot learns, and leaves it at that. On the other hand, Heinlein knows a lot about how things work in society, in this case concerning running a business, issuing stocks, and so on, in far greater detail than I can begin to summarize.

The plot is too clever by half. Where would the story have gone had not time travel abruptly surfaced half-way through? And while Heinlein stages some clever scenes near the end as Dan returns to witness his own abduction (and rescues his cat), it’s only in the very final pages does he speculate how time travel “works,” i.e. how could there have been two of him? Are there multiple realities, alternate timelines? He doesn’t really know.

\

Notes.

Heinlein lived in LA for a while (one of his famous early stories, “And He Built a Crooked House,” was set in Laurel Canyon), and you can tell from the street names he drops, e.g. the corner of Sepulveda and Ventura.

There’s a reference in 1970 to a “licensed semanticist” (10.4) and this is a reminder that General Semantics was an intellectual fad in the 1950s, of interest to science fiction fans (and the editor John W. Campbell) not long after they lost interest in Dianetics.

I thought it odd how the characters are casually “jumping” from city to town all over the western US. LA, Riverside, Big Bear, Denver, and so on. Presumably an indication of how fast travel would be in 2000.

And there are a couple places where Heinlein sneers at people who would sneer at progress. Page 149, Dan compares the wonders of 2000 to the realities of his past:

I wish that those precious esthetes who sneer at progress and prattle about the superior beauties of the past could have been with me — dishes that let food get chilled, shirts that had to be laundered, bathroom mirrors that steamed up when you needed them, runny noses, dirt underfoot and dirt in you lungs…

And p177 he wonders how he would use time travel.

‘Back’ is for emergencies; the future is better than the past. Despite the crape-hangers, romanticists, and anti-intellectual, the world steadily grows better because the human mind, applying itself to environment, makes it better. With hands… with tools… with horse sense and science and engineering.

(Ellipses in original.)