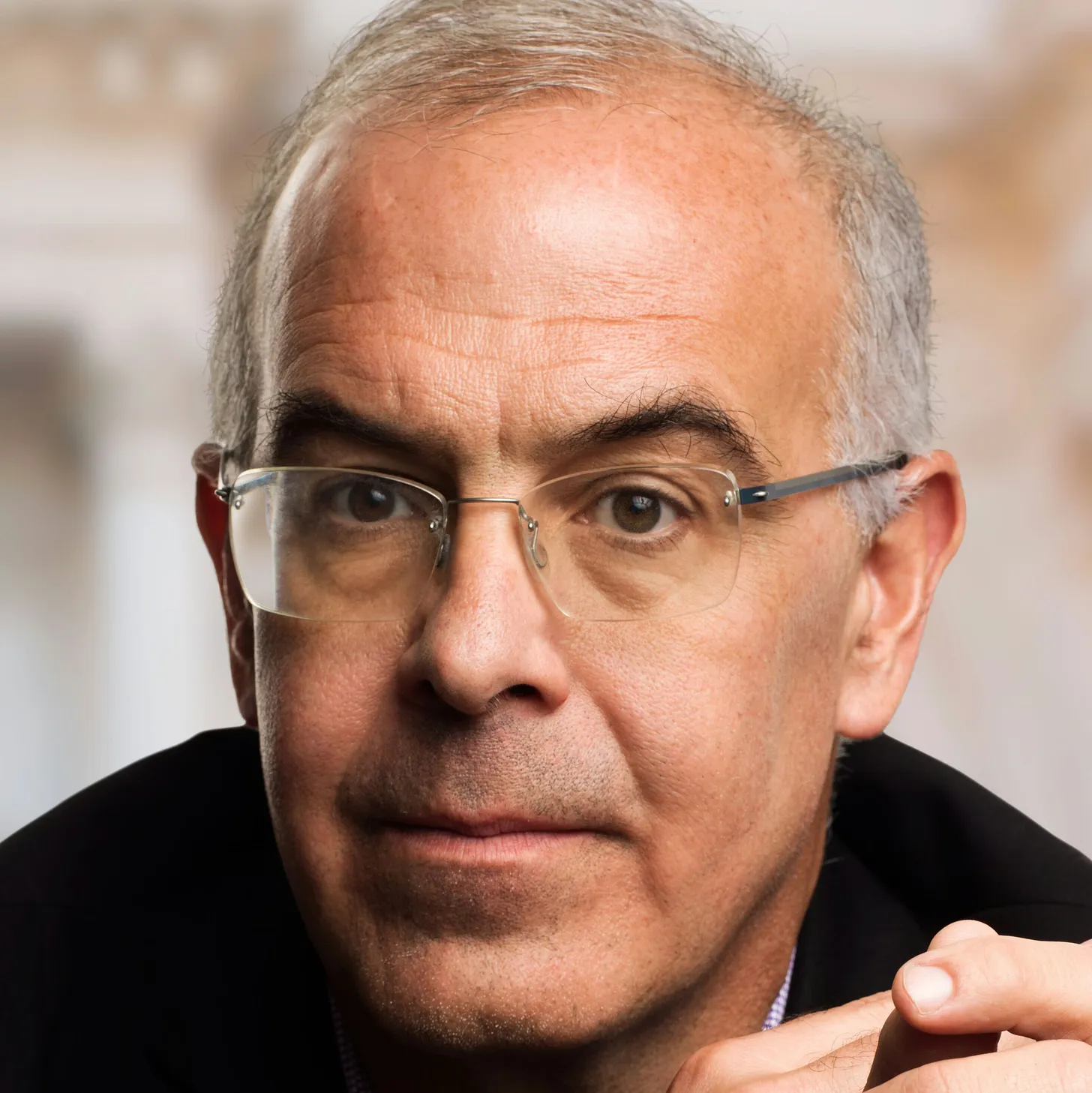

Not unrelated to yesterday’s posts. Two writers respond to the retirement of David Brooks from the NYT by examining the worldview he espoused — another version of restoring Western Civilization — and its crucial flaw — his unwillingness to let go of the presumptions of monotheism and learn what science has learned about the actual world.

OnlySky, Bruce Ledewitz, 18 Feb 2026: David Brooks wants to rebuild a humanistic culture, subtitled “To rediscover our values, we first have to forge a new foundation for them.”

Opening:

In January, David Brooks, a columnist at the New York Times, wrote his farewell column. Brooks is taking a senior fellow position at Yale University. The first half of the column told Brooks’ familiar story of America’s spiritual collapse into a “sadder, meaner and more pessimistic country.” But, in the second half of the column, Brooks explains that he is leaving punditry “to try to build something new.” That “something new” turns out to be something quite old. Brooks is aiming at rebuilding a humanistic culture in America. But he tries to do this without acknowledging the Death of God.

It can’t be done that way.

The writer then summarizes four decades of American political philosophy, and Brooks’ take on it. Just a sample:

The result of this decline in values is that America abandoned its “humanistic core,” especially in higher education, which moved away from teaching the elements in our civilization that “lift the spirit, nurture empathy and orient the soul… religious devotion, theology, literature, art, history, philosophy.” Based on a critique of Western colonialism, with which Brooks concurs, universities abandoned the study of Western classics. But they did not substitute anything else. Students no longer learned that there was such a thing as truth and that debate and persuasion are supposed to help lead us to it. Politics, and life in general, came to be seen as “ruthless power competition.” Young people in America became “cultural orphans.” Instead of teaching the humanistic tradition, our universities emphasized training in the individual pursuit of money.

The consequence of this educational shift is that college students, especially at elite institutions, are adrift. In a recent survey, 58% of students at Harvard report “no sense of ‘purpose or meaning’ in their life.” Brooks reminds us that most people cannot “flourish in a meaningless, nihilistic universe.”

(Note his inclusion of religious devotion and theology to his idea of a humanistic core of higher education.) He calls the idea of people making their own meaning in life the “privatization of morality.” Society must rely on a shared concept of the sacred, he says. Ledewitz wraps up and concludes:

The past collapsed for a reason

Despite my criticisms of Brooks, I don’t much disagree with any of this. I teach a course at my law school in philosophy of law that encourages students to reflect on the meaning of their lives based on some of these same classic sources. But Brooks’ retreat to Western Civ classes is a little old hat, not just because of the need to diversify the Western canon by race, gender and geography—Brooks would agree with that—but because he leaves out science entirely.

That omission reveals a larger gap in Brooks’ thinking. Classic humanism in the West was built on a very particular metaphysics and ontology: That foundation was monotheism. A beneficent God created the ordered and knowable universe that Brooks’ Great Conversation aimed at exploring.

But that understanding of reality is no longer the glue that holds us together. Before the reconstruction of humanism that Brooks seeks can take place, humanism will have to be put on a new foundation—perhaps on the foundation of the question asked by the Canadian theologian Bernard Lonergan: Is the universe on our side? That question brings the sciences back to the table. A new foundation does not require the abandonment of all religious literature, of course. But it does call for their reexamination.

Brooks believes we can just retrieve the past. But the past collapsed for a reason.

Brooks is proposing a worthy goal. But his column is a reminder that building a new civilization on a secular foundation is going to be a difficult undertaking. Much more difficult than David Brooks appears to realize. It will take more than a few course offerings in Western Civilization.

I have a couple thoughts. I think it would be difficult to find any point in American history when there was a shared conception of a religious monotheism that underlies the idea of any kind of humanistic culture. (Religion and humanism seem at odds.) That way lies MAGA myths and white supremacy. Second, this strikes me as just another case of an intellectual wishing he could justify, and bring back into place, the comfort of the religion of his childhood. Any honest understanding of the universe we live in, and of human nature, left all religions behind at least two centuries ago.

\\

Here’s another take on Brooks, from a very different perspective.

Robert Reich, 16 Feb 2026: Goodbye and Good luck, David Brooks, subtitled “His musings about personal morality have been thoughtful; his views about public morality and our political economy, far less so.”

As usual, I note these links in the morning, as I spend an hour browsing the news and opinion and science and science fiction sites, and only sit down to read an essay like this once I decide to blog about it. (Sometimes, once I read the piece, I delete the blog item.)

So, not having read this until in a moment, I’m wondering if there’s any overlap with the item linked above. Let’s see.

Friends,

New York Times columnist David Brooks, who personifies the oxymoron “conservative thinker” better than anyone I know, has announced he’s leaving his perch there. This deserves a mention because his punditry has been influential among neocons and neoliberals.

I’ve found Brooks’s musings over the past few years about personal morality and character provocative and thoughtful.

But when he has ventured into politics and economics, as he used to do quite regularly, Brooks has displayed such profound ignorance that I’ve often felt compelled to correct the record lest his illogic permanently pollute public debate.

Such has been the case with his columns arguing that we should focus on the “interrelated social problems of the poor” rather than on economic inequality, and that the two are fundamentally distinct.

Rubbish.

Reich has always been very concerned about inequality. He explains why, then returns to Brooks.

Brooks has argued that we shouldn’t be talking about unequal political power, because such utterances cause “divisiveness” that make it harder to reach political consensus over what to do for the poor.

Rubbish. Unequal political power hasn’t fuel divisiveness; divisiveness has been fueled by unequal political power.

Decades before Trump, the super-wealthy began spending vast sums on public relations, think tanks, and political campaigns, all of which vilified liberals — beginning with the Koch brothers and culminating with Elon Musk.

And so on. Reich concludes:

That David Brooks, among the most thoughtful of all conservative pundits, has not seen or acknowledged this — despite his commendable interest in personal moral development and character — is a sign of how far even the moderate right has moved away from the reality most Americans live in every day.

I wish Brooks well in his new pursuits. Whatever they are, I hope he begins to probe the important relationships between widening economic inequality and the crisis of personal morality he has readily and accurately acknowledged. I believe they are closely intertwined.

I’ve seen various concerns about inequality; Reich thinks it super-important and must be managed (via taxes on the wealthy, etc.); Pinker thinks it inevitable, and of little consequence; and Norberg — that book I’m currently reading — thinks it’s less of a concern since improved living standards have increased living conditions for everyone, compared to conditions a couple centuries ago. (A rising tide etc.) Even poor people (in most countries) have cars and TVs and electricity. And that’s true enough. (Another MAGA misconception is that countries like Vietnam and Nigeria are primitive hell-holes. They are not. There are plenty of movies about modern day life in those countries that show cities indistinguishable from most American cities. This is another theme in Norberg: how only in the past few decades, living conditions have improved worldwide… due to free trade and international cooperation.)

But there’s a psychological principle about how people’s happiness isn’t about some absolute standard, but about how they compare themselves to others, especially their neighbors. It’s relative. No matter how wealthy the entire world becomes, the relatively poor will still sore about the relatively rich, and this resentment (which we see in MAGA) will drive politics. The corrective to MAGA: Always zoom out: always look at the big picture.

\\\

That’s all for today. Tomorrow I’ll catch up on a bunch of short items that I won’t need to quote from (much) or comment on (much).