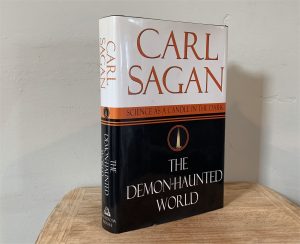

This is a book I think of as one of my foundational nonfiction books, i.e. a major book of central importance for its discussion of a critical theme. That theme, essentially, is that given the prevalence of pseudo-scientific claims in modern society (in the 1990s alien abductions were a popular theme) science is the methodology for determining what’s real and what’s bunk. Furthermore, there are psychological reasons for why people are attracted to pseudo-science (and religion) and put off by real science. And there are ways in which the ideals of science and democracy align.

This is a book I think of as one of my foundational nonfiction books, i.e. a major book of central importance for its discussion of a critical theme. That theme, essentially, is that given the prevalence of pseudo-scientific claims in modern society (in the 1990s alien abductions were a popular theme) science is the methodology for determining what’s real and what’s bunk. Furthermore, there are psychological reasons for why people are attracted to pseudo-science (and religion) and put off by real science. And there are ways in which the ideals of science and democracy align.

I first read it in 1996, not long after it was published. Rereading it now, I have to temper my assessment just a tad; it’s a less than perfect book, because it’s not a single sustained thesis and development leading to an overall conclusion. Rather, like Sagan’s first book THE COSMIC CONNECTION, it’s composed partially of pieces originally published separately, in magazines or newspapers, making the book instead a collection of essays around a common theme, and perhaps inevitably giving some topics more attention than you might think they deserve. In that, the book reflects its era: over 100 pages, chapters 4 through 10, discuss the then-current phenomenon of alien abductions, together with related topics of UFOs and the (legitimate) search for extraterrestrial life. That supposed phenomenon has pretty much faded away, I think, perhaps replaced by conspiracy theories and fake news on more strictly political themes.

A chapter-by-chapter summary follows, with comments, but first some highlights:

- The key chapter is 12, “The Fine Art of Baloney Detection.” Skeptical thinking in a nutshell. The positive steps for constructing a sound argument, and the counterpart steps for recognizing a fallacious or fraudulent argument. As it happens, the key points have been posted online, here: https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/01/03/baloney-detection-kit-carl-sagan/

- And a key metaphor, which later writers have cited, is the “dragon in my garage” described in chapter 10. How, for example, one might claim to have a dragon in one’s garage, and for every request for any kind of evidence, provide some reason why such evidence isn’t possible. What’s the difference between an invisible, incorporeal dragon, and no dragon at all?

- Chapters 2, 14, and 15 have strong discussions of the methods and values of science, how it’s different from pseudo-science and religion, and answering criticisms of science.

- And several of the later chapters, written with Ann Druyan, discuss how the values of science relate to those of democracy, [[ Implicitly aligning the values of religion and pseudo-science to those of authoritarianism; the current example being evangelical support for Donald Trump. ]]

- A running theme is about how science is a balancing act between being open to wonder, and being skeptical when drawing conclusions. Followers of pseudoscience are open to wonder but lack all skepticism. (Ch17 especially)

Detailed summary with some key points bolded and [[ my comments in brackets ]].

Preface: My Teachers.

Sagan recalls his childhood in 1939, especially the 1939 New York World’s Fair and the World of Tomorrow. His parents weren’t scientists, but they introduced him to skepticism and wonder, pxiii.6. They supported his idea to become an astronomer. He recalls no inspirational teachers. Schoolwork was rote, with no broad perspectives. With college came fulfillment; professors, etc. (see bullets). Still, his parents provided the most essential things…

- He mentions the value of being able to do back-of-the-envelope calculations.

- And, page xiv bottom: at U of Chicago “It was considered unthinkable for an aspiring physicist not to know Plato, Aristotle, Bach, Shakespeare, Gibbon, Malinowski, and Freud—among many others.” [[ I confess I had to look up who Malinowski was. ]]

- [[ My parents provided no such support. The best things my parents did was to fill the house with certain kinds of books: various kinds of encyclopedia, and the Harvard Classics. But they never provided story books, or chapter books, and they never consulted those encyclopedias themselves. When I started buying my own books – paperbacks from Scholastic, e.g., or science fiction – they were mostly indifferent, except to wonder why I couldn’t just check such books out of the library. My father was anti-elitist, sneering at scientists who thought they knew everything (as he thought) so far as to doubt religion. And I had no inspirational teachers, not even in college. I discovered everything through books, many of them encountered quite by happenstance. ]]

Ch1, The Most Precious Thing

Author tells of a limo driver asking him about various conspiracies and pseudo-science. Author reluctantly dissuades him, and asks what he knows about real science – not much. There are hundreds of books about Atlantis, and crystals, with no evidence. Little in public view of evidence, or skepticism, which doesn’t sell. In popular culture, bad science drives out the good; Gresham’s Law. Every generation thinks educational standards are decaying, e.g. quote from Plato.

- [[ Note! —just as some always think the “good old days” were in the past, it’s common to think “kids these days” don’t measure up to past standards. Neither is true. ]]

Yet such ignorance is more dangerous now than ever – long list of topics, p7t – given how politicians ignore the experts. How do Americans make decisions about such matters?

Hippocrates brought some insight into medicine that had previously been entirely superstitious. He emphasized observations. Most of this was lost during the dark ages. [Because religion] Queen Anne, late 17th century. Things have improved enormously since then. (Despite Christian Science.) Life expectancy is increasing. For humanity to continue to thrive requires science and technology. Not that they are always for the good: there have also been nuclear weapons and all the other military applications; thus the image of the mad scientist. …

Do we care what’s true? Does it matter? P12. Serious question. Some think too much knowledge is damaging; author disagrees, better to know that persist in delusion. A maturing. Anyway, we are stuck with the discoveries of science; there is no way back. Yet pseudoscience keeps getting in the way. Based on insufficient evidence or ignoring contrary evidence. Pseudoscience speaks to emotional needs; to fantasies about personal powers; reassurances of our importance.

Pseudoscience is the counterpart of misunderstanding science. It reflects the way humans have always thought. The cases here are mostly American, but these afflictions are present around the world. Many examples p15-16. Most recently, TM, transcendental meditation. Russia encouraged ideological religion, and considered critical thinking dangerous. [[ as do some modern state educational boards ]] China. Summary 19.4.

So what’s going on? The situation relates to what religions are and how they arise. There is a natural selection of doctrines, how some thrive and most quickly vanish. There’s a continuum from pseudoscience and superstition to religion based on revelation. Some religions reign in their excesses; yet they are reluctant to challenge their extreme fundamentalists.

Pseudoscience is not erroneous science. The former often frame hypotheses that are immune to potential disproof, and often appeal to conspiracy theories.

We don’t appreciate how our perceptions are fallible—mention here of the first Gilovich book, p21m. Science better appreciates human fallibility.

And it’s just as important to teach the methods of science, as its conclusions. Otherwise scientific claims seem arbitrary. And to acknowledge how in the history of science there were often stubborn refusals to accept new discoveries…

Ch2, Science and Hope

To love science is to want to tell the world about it. More than a body of knowledge; a way of thinking. Foreboding—p25b, about the dumbing down of America. Can already be seen in the media. “A Candle in the Dark” was a 1656 book attacking the notion that anything bad must be due to witches. Now, any kind of threat or stress seems arouse the demons of ignorance.

Science doesn’t claim to know everything. It’s not perfect, just the best instrument of knowledge we have. It has a built-in error correcting mechanism. Error bars. Absolute certainty is unattainable. Mistrust arguments from authority. Scientific findings are at times unsatisfying, but there is deep satisfaction in understanding the methods of science. Science can be “spiritual” without presuming anything outside the realm of science.

Science may be hard to understand, but it delivers the goods—no religion delivers prophecies with anywhere near the accuracy of science. This is not ‘faith’ in science, it is using what works best. It works best because of that error-correcting machinery. Science is relentlessly self-critical, in papers, in conferences, in theses.

Science is not arrogant; it’s humble in its taking seriously what nature tells it. Thus Newton was superseded by Einstein, p33. Now, even general relativity may break down, e.g. if gravity waves don’t exist. [[ They’ve been found since this book ]]

You never hear of religion questioning itself and rewarding critics. Science always reminds you that you might be wrong.

Example: two paragraphs about electrodynamics. From Einstein: concise and clear. Scientists experiment wherever possible. Whereas metaphysics has no laboratory.

There are four main reasons to convey science to every citizen.

- Science is the means to escape poverty and become wealthy.

- Science provides early warning systems for damage we may be doing to our world.

- Science teaches us the deep issues of our origins and fates, our place in the universe, in a way no other endeavor has done.

- The values of science and democracy align. Without them both, we risk being a nation of suckers.

What would an extraterrestrial think of us by reading our papers?

Ch3, The Man in the Moon and the Face on Mars

Every field of science has its counterpart pseudoscience—see long para p43. Author starts with those related to his area of study, the planets: the face on Mars, and that aliens are visiting earth.

Cultures have seen many things in the face of the moon; in ours, a “man in the moon.”

Infants recognize faces. It’s hardwired. And so we sometimes see faces from patches of light and dark where there are none. Thus there are geological formations named faces or body parts. Shapes in clouds, or wood grain, etc. Insects that have evolved to look like sticks.

Recalls book by John Michell, and Richard Shaver and Antonin Artaud, who thought artifacts like these were evidence of ancient civilizations, p47, dismissing rational explanations as “materialism” p48t, and that nature intends more than that.

Then we had the canals on Mars. Inspiring much popular fiction. But of course spacecraft never found them. They were errors of pattern recognition. The advent of space flights brought thousands of amateurs perceiving amazing things. We see familiar shapes in galactic nebulae. Geological features look like pyramids.

And then Cydonia, on Mars, and the ‘face’ found by Viking in 1976. Speculation went wild. Accusations of NASA cover-ups. Tabloids made wild claims. E.g. about suppression of evidence to avoid world panic. But scientists are not secretive by nature.

So what do we know about the ‘face’? Blurry images. Worth further examination, however unlikely they’re alien artifacts.

Such phenomena will not go away. Further ‘discoveries’ are announced. Other tabloid stories., p56-57. It would be funny if many readers didn’t take the tabloids quite seriously. Some people need the thrill of such possible discoveries, p58. The tabloids have the pretense of using science to validate ancient faiths and superstitions.

But there are enough real wonders out there without inventing any.

[[ Note he doesn’t mention Richard Hoagland, the most notorious author to promote the “Mars Face”, even indirectly. ]]

Ch4, Aliens

Author describes scenario of waking in the night, being abducted, probed. Sometimes not remembering until later. Polls indicate widespread belief in such abductions, from UFOs. Who are we to doubt them? Yet, how could such an alien invasion be taking place? Why would they be doing that? Why not in a more efficient way?

How strong is the actual evidence? The early ‘flying saucers’ seemed partly plausible given the number of stars out there. And there were plenty of photos.

The 1841 book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds told of similar events throughout history—of scams and delusions. Usually with some political or religious motivation. Mesmer.

Also Martin Gardner’s Fads and Fallacies book. More examples. Thus the fallibility of humans might easily explain flying saucers. It all depends on evidence. The more we want something to be true, the more careful we have to be.

Examples of misquotations, frauds, pranks, hoaxes. The last go back to Richard Shaver and his Lemuria, in Amazing Stories.

Similar credulousness and shoddy standards of evidence are seen in reports of crop circles. Enthusiasts credited superior aliens. In 1991 two pranksters admitted being behind them. Copycats followed. But few heard about the hoaxers.

The tools of skepticism aren’t difficult, but are seldom taught—too many politicians, advertisers, and religious leaders rely on discouraging skepticism.

Ch5, Spoofing and Secrecy

UFO is a more general term than flying saucer. We hear many claims, but none where evidence requires them to be alien spacecraft. We seldom hear about those that are explained. Author has spent some time concerning UFOs. People ask if he ‘believes’ in them. Many have no problem assuming a government conspiracy to cover them up. Project Bluebook was so shoddy it reinforced that impression. And it makes perfect sense that the government should study the phenomenon. Military balloons were a thing. Roswell is likely explained by such balloons carrying classified equipment.

In this era there was much experimentation into missiles for carrying nuclear bombs, and into how they reentered the atmosphere. Those indeed were top secret. Another idea is ‘spoofing’ where an enemy craft sees how far they can get into southern US airspace before being detected. Again, such incidents would be secret. Also, routine surveillance of tv, radio, and mail is subject to secret, and even FOIA releases are heavily redacted…

The most credulous UFOlogists seem unaware of this secrecy culture, taking it as evidence of a government coverup of alien spacecraft. And the so-called MJ-12 documents, likely a forgery that served the interests of its discoverer. (also: Deuteronomy, p 91m, and the Donation of Constantine.)

And how could such a worldwide conspiracy be maintained? 92.5 Why wouldn’t NASA be interested? Or the DoD? This isn’t to say the subject isn’t worthy of study. And there are many other (unlikely) explanations. Sidebar about a secret government plane, Aurora, which the air force denies exists.

[[ This whole chapter reads like a sidebar, reflecting Sagan’s special interest in debunking UFOs. ]]

Ch6, Hallucinations

Consider the advertisements in an issue of the magazine UFO Universe, p99, all appealing to unlimited gullibility.

Sometimes someone in ‘contact’ with aliens will ask Sagan for a question to ask the aliens – but questions about math, say, are never answered. Aliens seem preoccupied by current concerns of humans.

George Adamski. Betty and Barney Hill. James E. McDonald. Author met the Hills.

Another kind of explanation are hallucinations. Drugs. Some cultures venerate them—vision quests. Religious quests. A signal-to-noise problem. Some percent are subject to them; it’s part of being human. The stories alien abductees tell are like those in other cultures of meeting goblins, elves, etc. Only recently in human history did children sleep alone; thus their being afraid of the dark.

Once the idea of extraterrestrials became popular, people imagined contacts with aliens. But after the canals were debunked, stories of visits by Martians disappeared….

Ch7, The Demon-Haunted World

Belief in demons was widespread in the ancient world. They were taken to be natural, not supernatural, often thought intermediaries between humans and God. Socrates, Plato. The early church tried to distance itself from ‘pagan’ beliefs. But St. Augustine was vexed with demons. Psellus in the 11th century. Incubi and succubi. The external reality of demons was almost entirely unquestioned from antiquity through late medieval times. The obsession reached a crescendo with a Bull of 1484, by Pope Innocent VIII, which justified the pursuit and torture and execution of ‘witches’ throughout Europe. The Protestants followed suit. Handbooks about how to torture and kill witches. Accusation was sufficient; confessions were exacted through torture. The priests were obsessed with the details of orgasms and bodily parts. P122 in one small city there 100 or so immolations in one year.

Anyone who doubted the justice of this was said to be attacking the church and thus committing a mortal sin. The inquisitors and torturers were doing God’s work. Heresy was also a crime, e.g. attempting to publish an English language bible, Tyndale in the 16th century.

Burning witches has declined since then. But we still use language like pandemonium and most Americans say they believe in the Devil; modern Christians accuse rock music of being demonic.

And what did these demons do? They interfered with copulation; they transferred human semen and transferred it. Either demons really exist, or for centuries, unto today, most people suffered shared delusions.

Which brings us to alien abductions. In many cultures there are stories of gods appearing to humans, e.g. the Greek gods impregnating women. Lilith. A 1645 case about fairies.

Now we have alien abductions, beginning with a 1982 book. Edward Gibbon describes the credulity of the ancients. James I wrote a book on demons. They were imagined to be everywhere.

If the aliens are real, why were there no reports of flying saucers before 1947? And why haven’t their experiments finished by now?

In fact, some believe the aliens are really demons—the Raelians; Whitley Strieber; fundamentalist tracts. Christians are split on whether scripture allows for the existence of aliens, e.g. Hal Lindsey.

Since the early 1960s author has argued that UFO stories were crafted to satisfy religious longings. They’re rewrites of older stories about supernatural beings. Our hallucations interpret what we see according to the assumptions of culture of the day, see 131t. People remember fragments of experiences from childhood that emerge later. And now popular culture is full of alien imagery, often with the assumptions that aliens will be small framed but with large heads.

What most reports reveal is a failure of imagination and a preoccupation with human concerns. “The believers take the common elements in their stories as token of verisimilitude, rather than as evidence that they have contrived their stories out of a shared culture and biology.”

Ch8, On the Distinction Between True and False Visions

If we see something or hear a sound and wonder if it’s just our imagination, do we tell others? Depends on the surrounding people and culture; on what other people might think, doubt or credulity. In therapy reticence is often overcome. Hypnosis encourages fantasy, or incorporation of the hypnotist’s beliefs. Hypnotists can cue their patients. People are suggestible; they’ll accept false evidence and claim they saw it too, 139m; false memories. Children especially. Reagan famously told of liberating concentration camp prisoners—but he didn’t; it was a movie. We form memories that are seldom challenged by new facts.

Most common are apparitions of religious figure, e.g. the Virgin Mary. Shrines are built; the local economies thrive.

In 1400 a book [title of this chapter] was written about which visions could be taken as true and which not. Authorities were not to be challenged; ordinary objects were compelling.

Motives are easy to imagine. That doesn’t mean they just made things up. Many were likely species of dream—or hoaxes and forgeries. Such apparitions were welcome by the church in medieval times. This changed around the time of Reformation; they then became threats church order. Thus Joan of Arc was burned at the stake.

Needless to say, the requests of Virgin Mary were prosaic—e.g. pay your tithes. Never any revelations of knowledge that could only have come from God. Why doesn’t Mary approach the authorities herself? None of the saints criticized the torturing and burning of witches.

There are many parallel with the alien abduction stories. In our time there are as many apparitions of Jesus.

Why would people invent abduction stories? Perhaps simple notoriety. Like claimants of product tampering. Which happen even without therapists encouraging them. As they are for alien abductees.

Ch9, Therapy

Author cites Harvard psychiatrist who interviewed abductees and became convinced—based entirely on the emotional power of those experiences. This is a bad guide to truth. Perhaps they are remembering childhood sexual abuse. Therapy tries to draw them out. But memories can be confabulations too. Claims of alien abduction are similar to ‘recovered memories’ of childhood sexual abuse. A third class of claims come from satanic cults. To some, satanism is any religious belief system other than their own, p159b. Much abuse has been done in the name of religion. Consider five cases. Many such cases don’t hold up to scrutiny. Long example involving man who went to prison for 20 years. Why does all this happen? Perhaps a way for evangelicals to ward off threats of new religious movements, 163b. They have no patience for skeptics.

All three of these classes of ‘recovered memories’ have their own specialists. What is the larger picture? A kind of hysteria; people are suggestive and gullible; the specialists validate their fantasies. In a few cases therapists have been found guilty of negligence. Therapists have no motive to identify simple solutions.

[[ As in much of this book, the lessons aren’t so much about, say, alien abductions per se—it’s about how easily we can fool ourselves, or be misled by others, or manipulated by circumstances, into believing things that aren’t real. ]]

Ch10, The Dragon in My Garage

Suppose author claims to have a dragon in his garage, and you want evidence. But it’s invisible, incorporeal, and so on—no evidence is possible. Even if many people make such claims. Scant evidence is likely faked. The best conclusion is to wonder why so many people are having delusions about invisible dragons. Similar reasoning applies to claims of alien abduction.

Recalls case from 1954 about a physicist who had an elaborate fantasy life of a far future starship pilot. The psychoanalyst found himself being sucked into the fantasy. Until the patient confessed, he made it all up. The two had switched roles.

Consider radio search for ETs. Signals detected from CTA-102, later called a quasar. And in 1967, pulsars. All the reasons scientists are careful before announcing aliens. P180: “I try not to think with my gut. … Really, it’s okay to reserve judgment until the evidence is in.”

We must rely on the evidence. No anecdote is good enough. And there isn’t any verified evidence that couldn’t have been scammed. Photos are faked. Scars are claimed but can’t be seen. Explanations resort to ‘other dimensions’, a notion from physics; borrowing its language without its methods.

What’s needed is critical thinking, even for psychiatrists. P184. As you would when buying a used car. A 1995 TV broadcast of an alien autopsy might easily have been faked. No physical evidence from alien spaceships has ever turned up. Discoveries of real evidence would be momentous.

It’s good to keep an open mind. But evidence must be strong.

Ch11, The City of Grief

The previous 7 chapters were summarized in Parade magazine (a supplement to many Sunday newspapers) in 1993. It provoked much reaction, including misunderstandings. What follows is a representative sampling of mail on the subject… almost all skeptical of his conclusions, many spouting crazy ideas of their own. Including religious ones.

Ch12, The Fine Art of Baloney Detection

Author recalls parents and how there are moments he thinks perhaps they’re not really dead. There’s something within us ready to believe in life after death. Regardless of whether there’s any sober evidence for it. Why don’t channelers ever provide information otherwise unavailable? Secrets lost to the past? Better the hard truth than the comforting fantasy, 204.4. Examples: JZ Knight and Ramtha. Ramtha offers no details, e.g. 205t, only homilies. –another good example of specific evidence that never turns up. Another, 205b.

JBS Haldene supposed in an infinite universe, everything would happen again… infinite times.

We tell our children fabulous tales to soothe them. They get disabused of Santa Claus, etc; but not the faith of religions. Quotes from Tom Paine, TH Huxley p208. Their thoughts were about religion, but similar remarks can be made about modern advertisements—claims we’re not supposed to question. Paid endorsements corrupt attitudes about scientific objectivity. New Age Expos promote highly questionable products. Psychic healers. Astrologers. Dowsers. Miracle workers.

Scientists employ a baloney detection kit. Tools for skeptical thinking, p210. Skeptical thinking is about constructing a sound argument, and recognizing a fallacious or fraudulent argument. [see here: https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/01/03/baloney-detection-kit-carl-sagan/ ]

- Try to independently confirm ‘facts’

- Encourage debate on the evidence

- Arguments from authority carry little weight; at best science has experts.

- Think of all possible hypotheses to explain the evidence, and think of ways each might be disproven. Keep going until one is left. (Compare the issue of jury trials, where people make up their minds early.)

- Don’t get attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours.

- Wherever possible, quantify.

- Every chain in an argument must work, not just most of them.

- Occam’s Razor: choose the simpler of two hypotheses that explain the data equally well.

- Ask if the question is falsifiable

Key is reliance on carefully designed and controlled experiments. Variables must be controlled. Often experiments must be done “double-blind”.

We must also recognize fallacies of logic and rhetoric—used often in religion and politics, where often two contradictory propositions must be justified.

- Ad homimen

- Argument from authority

- Argument from adverse consequences

- Appeal to ignorance. (absence of evidence is not evidence of absence)

- Special pleading

- Begging the question

- Observational selection, e.g. counting the hits and forgetting the misses

- Statistics of small numbers

- Misunderstanding the nature of statistics

- Inconsistency

- Non sequitur

- Post hoc, ergo propter hoc, i.e. it happened after, so it was caused by.

- Meaningless question

- Excluded middle, or false dichotomy

- Short-term vs. long-term, a subset of excluded middle

- Slippery slope, also related to excluded middle

- Confusion of correlation and causation

- Straw man

- Suppressed evidence, or half-truths

- Weasel words

Examples of how the tobacco industry argues against causation from tobacco to lung cancer. And Du Pont with Freon. [[and deniers of climate change.]] Aren’t low-tar cigarettes a tacit admission…? Data is faked. What does this say about how well free enterprise can police itself? Part of tobacco’s success is due to unfamiliarity with critical thinking and the scientific method.

Ch13, Obsessed with Reality

Epigraph about a man who didn’t worry his ship might sink; he sincerely believed it would not. But from the evidence, his sincerity was not earned (and the ship sank).

There’s a whole range of ideas that are appealing, but not subject to the Baloney Detection Kit by their advocates—long list, p221-2, from astrology and Bermuda triangle to scientology and the remains of Noah’s ark.

Some fundamentalists reject these on the ground of Deuteronomy, 222b—not because they’re false, but because they’re unsuitable for a follower of god. A 12th century writer was more insistent that they just don’t work. It’s always about how good the evidence is. Examples of claimants who fail when examined privately.

And then the long tale of Carlos, a new age figure, supposedly an ancient soul that would take over the body of Jose Luis Alvarez, and their appearance in Australia in 1988, to much media attention. –But it was all an elaborate hoax staged by James Randi with an assistant. The press didn’t do due diligence in checking on his background.

Such fraudsters can be dangerous in situations like faith healing… some people do get spontaneously better, but they likely would have anyway. Placebos often work. Death rates drop before major holidays and events…then rise afterwards. Mark Twain criticized Christian science; cults almost began about JFK, and Elvis.

The Australian press was criticized. But there were still a few believers! What did it all prove? That how readily people are willing to be fooled. And the few random successes sometimes convince charlatans they really do have powers!

Another lesson: if someone is bamboozled long enough, they reject evidence of the bamboozle. [[ Sunk-cost fallacy and religion! ]] it’s too painful to acknowledge we’ve been taken. Thus séance tricksters, and crop circle hoaxers, when they confess, the news doesn’t get out, or believers always say, but what about this other case.

Sending out the same horoscope to 150 people; almost all see themselves in it. The required evidence for sexual abuse, e.g., is often so broad everyone will exhibit some symptom or another.

And these things happen in all nations, not just the US.

Ch14, Antiscience

Epigraph summarizing new age beliefs in which there is no objective truth.

Motivations for doubting the framework of science—science envy; it can be dismissed, p247.

Edward U. Condon and the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Arthur Miller wrote The Crucible. Concon was impugned on the ground that quantum mechanics was ‘revolutionary.’

Quantum mechanics is impossible to understand without the math. Purveyors of religion and new age doctrines often use the same ploy: it takes 15 years to understand all the ‘mysteries’. [[ Jerry Coyne points out that theologians often use this argument. ]] The difference is: we can verify that QM works. And shamans claim their cures work. But do they? Also, science is open to everyone; those who question non-rational authoritarianism are considered disloyal and unfaithful.

Certain kinds of folk knowledge are valuable—but they don’t extend to general principles.

Science has for centuries been attacked by antiscience. That it’s subjective, like history, written by victors to justify themselves—list of historical examples, p252-3. [[ Knowing such examples is another example of being savvy. ]] This subjectivity has been recognized for centuries. Historians have biases, and can try to overcome them. Scientists have biases too, and make mistakes; but it has built-in error-correcting machinery. And science, unlike history, can do experiments.

There’s also the claim that science is arbitrary or reason is an illusion. Ethan Allen—how to argue this without using reason? 255m. [[ Isaac Asimov made the same point, somewhere. ]]

Within the framework of science any scientist can prove another wrong and make sure everyone else knows about it, 255b. Fred Hoyle was so productive of ideas that there were many efforts to prove him wrong, and these led to new areas of knowledge. All the major scientists made serious mistakes. Even author himself: about Venus, Titan, Kuwaiti oil wells.

Arguments about the motivations of this or that scientist are irrelevant if their results work—just as arithmetic is the same everywhere. Examples of arguments against Newton and Darwin. Analogous to Jefferson and Washington owning slaves. Habits of our age that may be considered barbaric in future ages, p259b. Thomas Paine stood out.

Ideas can be misused, but should not be dismissed; who would decide which ideas to suppress? Ideologues do so: Nazi science; Lysenko in Russia, who hampered Soviet science for two generations. And Americans who promote the pseudoscience of creationism, and their efforts to prevent evolutionary theory from being taught in school.

Ch15, Newton’s Sleep

Epigraphs from Blake, and Darwin (about ignorance…)

Blake seems to have meant to criticize the narrowness of Newton’s physics; and it’s true that science rules out, lacking evidence, many wonderful ideas: spirits, souls, angels, and so on. The term scientism is used to condemn the idea that we are nothing but material beings, despite the attraction of psychic or spiritual. Yet there are many things once thought miraculous that we now understand.

Still, life seems unfair; it would be nice if there were some eternal reward, or a second chance. Cultures that believe such things might have a competitive advantage. People want to believe such things. Some people resent the limits of nature that science identifies.

Or that science is too simple-minded or ‘reductionist.’ That it will all be explained by a few laws. Newton’s clockwork universe. That’s just the way the universe is. It used to be thought some ‘vital force’ must exist to explain life. Study of DNA was considered reductionist. But with that we understand are organisms work. Reductionism works especially in physics and chemistry. The universe might have been different, but it isn’t.

Attempts to reconcile science and religion go back to Aquinas. Yet the tenets of religion can be tested scientifically—and this makes believers wary of science. Examples p275. Consider prayers of other religions. Which prayers work, if any? Why are they needed, if god knows all? Why don’t monarchs live long, when so many pray for them? This is data. Those fundamentalist sects that take stands on matters subject to disproof have reason to fear science. If some central tenet of faith were disproved, what would they do? Fortunately some tenets are difficult to prove or disprove. Are there some things it’s better not to know? Author suggests it’s better to know.

Ch16, When Scientists Know Sin

Oppenheimer’s comment about the Manhattan Project; Truman never wanted to see him again. Charges that products of science can be used for evil probably go back to the domestication of fire. It’s a statement about human nature. Some try to have it both ways by attributing evil uses to other agencies. Edward Teller advocated the hydrogen bomb, over Oppenheimer’s concerns. Author warned against prospect of nuclear winter in the 1980s. Teller claimed that he discovered it—but never told anyone. Teller advocated using nuclear bombs for all sorts of purposes. He sold Reagan on the idea of Star Wars. His ideas might be seen as attempting to justify the invention of the hydrogen bomb.

No realm of human endeavor is not morally ambiguous. Aphorisms. Maintain religion. All the slaughter in Joshua and Numbers. You can find something in the bible to justify anything. It is a particular responsibility of scientists to be aware of ethical issues, and issue appropriate warnings.

Ch17, The Marriage of Skepticism and Wonder

It’s impossible to literally tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. We try to weed out bias among jurors. Shouldn’t such biases be accounted for in other areas? We should consider ourselves and our institutions scientifically, with no areas off limits. All societies have incest taboos and belief in supernatural gods of some sort. And a world of myth and metaphor. How can we enjoy the fruits of technology and still believe in creationism or astrology?

True, scientists can sound smug and offensive. Supporters of superstition and pseudoscience are people too. Aren’t their comforts deserving of respect? Or is staying silent harmful to rigorous thinking? A prudent balance takes wisdom.

CSICOP, founded in 1976 by Paul Kurtz, helps challenge credulous reports of every faith healer and visiting alien. And yet the skeptical movement creates polarization, us vs. them. They’re not all crackpots; many are sincerely exploring alternatives to conventional answers to various issues. Yet the defenders dismiss skeptics as atheistic materialists. It’s more important to some that people feel strongly. And the skeptics are a tiny minority.

There are a few ideas from ESP that *might* be true. Author could not endorse Objections to Astrology; some criticisms were beside the point. Astrology remains popular.

Science must be open to any idea, no matter how bizarre or counterintuitive, and at the same time ruthless in its skepticism of all ideas. Creative thinking and skeptical thinking. There are many absurd-sounding ideas that are nevertheless true. Better to be skeptical than credulous. The marriage of these skills should be taught to every child.

Ch18, The Wind Makes Dust

Why should science be hard to learn and hard to teach? Perhaps because science is relatively new. Many cultures made inventions; only ancient Greece developed science, due to numerous factors over 1000 years, p310t.

Yet the early Ionians made no lasting impression. What’s needed are unfamiliar challenges, where fundamental changes are needed. Early Greek science was riddled with error. And science requires experiment. The later idea that the universe was created by one Supreme God was a motive in the development of modern science. Monotheism.

And yet—recall a vignette of Kalahari desert people on a hunt. Forensic tracking skills. Science in action. Like understanding craters on other planets. Techniques passed on from generation to generation. A scientific bent that’s been around for millennia. Skills that enhance survival.

What happened in ancient Greece was the idea of systematic inquiry, and the notion that laws of nature, not capricious gods, govern the world.

So…a proclivity for science is embedded deeply with us, all times and cultures.

Ch19, No Such Thing as a Dumb Question

Stone age tools were the same for long periods of time—techniques were passed down by tradition. When new things must be learned, students complain about relevance, respect for elders diminishes. The skill needed is learning to learn. Young kids ask all sorts of questions; high school seniors memorize ‘facts’. As if asking deep questions is a social blunder. Students must be given tools to think with.

Americans are worse in most subjects than many other countries; why? The larger issue is producing a scientifically literate public. Examples of how few know basic facts 324b. Even more important is understanding *how* we know these things. Religious texts say the earth is flat, and only 6000 years old; and people believe what they want to believe, e.g. about evolution. Children need hands-on experience. American kids need to do more homework. Workers are often incompetent.

Wonders of science. Questions framed to trigger discoveries, p330-3.

Scientists need to talk to general audiences differently than they do other scientists. Speak as simply as possible. Learn which analogies work, etc. List of popular writers, p336

[[ At the same time I’ve begun to wonder if it really matters if modern adults don’t know this stuff? Making a living and being aware might be independent. ]]

Ch20, House on Fire

Parable about a man who escapes his burning house while inside are his sons unaware of the fire…

A short version of previous chapter was published in Parade. He got feedback from students, p339. And from parents, 341. (Note comments about not wanted to stand out, or show up the other kids.) Religious resistance. These issues affect all subjects, of course. Exhibits. Museums—wildly popular. Discusses the film Powers of Ten, and the Sciencenter in Ithaca, as effective ways of teaching science.

Ch21, The Path to Freedom

Only the educated are free.

Recalls slaves, especially in Maryland, 1820, when children separated from their parents, and whipped, as endorsed by the Holy Bible. Illiterate. And the slave boy who became Frederick Douglass, by learning to read.

Books are the key to examining the past. But many Americans are only barely literate. Those with the lowest rates are poorer and less likely to vote. It helps to have parents who read. Good nutrition. Criticizes the book The Bell Curve – which argued that programs to help the poor didn’t work and should be abandoned — for confusing correlation and causation. Programs like Head Start do work.

Tyrants and autocrats understand that learning can be dangerous. Early America had a high literacy rate; now not so much. We bear the costs of illiteracy…

Ch22, Significance Junkies

Television is profit-motivated. Can science programming be successful on TV? Basketball is relatively modern. Can it be used to teach science and math? People absorb sports statistics, and financial news.

Some people are impressed by hot and cold ‘streaks’. But using BDK, such streaks are to be expected. Recall Gilovich. We see streaks and find them meaningful—we’re junkies for significance. Isn’t it harmless to entertain such ideas?

Scientists in TV shows are usually mad, power-crazed. We get credulous shows like In Search Of. (These exhibit much thirst for wonder, but no skepticism.)

The X Files, p374, always choosing the fantastic explanation. Star Trek, which doesn’t come to grips with evolution. Star Wars’ parsec.

Science covers in the news is nil. Author lists several ideas for more science on tv, p377.

[[ An example of how the whole book, and even individual chapters like this, is a grab-bag of assorted ideas not well coordinated. The title here alludes to one specific point, about seeing meaning in randomness, while most of the chapter is about science on TV. ]]

Ch23, Maxwell and the Nerds

Reagan quote: “Why should we subsidize intellectual curiosity?”

Everyone is stereotyped. Even if valid on average, stereotypes are bound to fail in many cases. Recall the bias against women in science. How skeptics tend to be men. How scientists are nerds. There may be reasons why this is sometimes so.

You can’t just order scientists to make some discovery. Suppose in 1860 you imagined a [television], and ordered it to be built. Couldn’t have done it. The technology that made it possible came from James Clerk Maxwell, who was called dafty; he was a nerd. And he was interested in how electricity makes magnetism and vice versa. He developed four equations to describe what was known about both. And what they would be in a vacuum—a changing field of one generates the other. And would propagate at the speed of light. He imagined an ‘aether’ for such waves to travel through. But that was ruled out by Einstein. It’s counterintuitive to think of these fields as not being somehow mechanical. Nature is stranger than human common sense. P392m From these came radio, TV, radar. And much else. Long Feynman quote. Yet Maxwell was never knighted, nor has he been celebrated by film or TV.

Now such electromagnetic signals are being sought from extraterrestrial civilizations. But congress pulled funds for SETI after one year. Yet again and again, discoveries made by scientists have led to widespread technological and medical advances. While politicians like Proxmire make fun of such proposals. The failure of the SSC was due in part to the scientists not making a comprehensible, easy to understand case for it. And the free market would never fund most of these discoveries. No one can predict which research will have practical value. Cutting off basic research funding is like eating the seed corn.

Ch24, Science and Witchcraft

The 1939 world’s fair presented a vision of the future reached through science. But it was oriented to consumer products; it could have been more, with some basic science, as a way of thinking.

50 years later, author wonders if Americans know how to keep their freedom. 1798, the Alien and Sedition Acts. Criticism of Federalist officials was a crime. The French and Irish were seen as threats, undeserving of equal rights. Then there was 1942 and the Japanese; now there’s a war on drugs.

Recall again the witch hunts. In 1631 von Spee wrote a list of charges against those trials—the list follows, for 4 full pages. Whatever happens is proof of witchcraft. And eventually the accusers are accused themselves… A few, like von Spee, protested. Eventually the witch hunts stopped, and not abolished by the church until 1816.

Quote p413 about the witch mania:

Why was it resolutely supported by conservatives, monarchists, and religious fundamentalists? Why opposed by liberals, Quakers and followers of the Enlightenment? If we’re absolutely sure that our beliefs are right, and those of others wrong; that we are motivated by good, and others by evil; that the King of the Universe speaks to us, and not to adherents of other faiths; that it is wicked to challenge conventional doctrines or to ask searching questions; that our main job is to believe and obey—then the witch mania will recur in its infinite variations down to the time of the last man.

Recall Goebbels, and Orwell’s 1984, how they tried to rewrite history. Now [as the author writes] we have the sudden demonization, 1991, of Saddam Hussein. And in the war on drugs, where evidence is distorted and invented. And now with changes in media – fewer newspapers; control of TV by a few corporations, etc. 416t. “It’s hard to tell how it’s going to turn out.”

Nationalism is rife in many parts of the world. Science is international. Note how often scientists are among social critics. Linus Pauling. Edward Teller. Again, the powers of science must come with ethical focus.

[[ how relevant is this chapter in the age of Donald Trump! ]]

Ch25, Real Patriots Ask Questions

The methods of science can be used to improve social, political, and economic systems. Every change of policy is an experiment. Policy can be tested; it would be a waste to ignore results of social experiments because they seem to be ideologically unpalatable, 423b.

Yet humans tend to make the same mistakes over and over. Many of the founding fathers were science oriented. Jefferson described himself as a scientist. He helped spread democracy around the world. Conservatives denounced his Declaration, for its ideas of rights for all, the idea that people could lead themselves. And yet people are easily misled. Thus the balancing of powers. Later he advocated term limits for the president, and a bill of rights. Where are the likes of Jefferson and the other founders today?

Freedoms of expression are broad. There is no mandatory or forbidden ideology. Quotes from narrow-minded abortion critics p430: “Let a wave of intolerance wash over you… Yes, hate is good… Our goal is a Christian nation…We are called by God to conquer this country…We don’t want pluralism.”

But our system has error-correction mechanisms; the exchange of ideas, the criminal justice system.

Once people were tortured for doubting religious leaders; gradually Christianity became more tolerant. The Bill of Rights decoupled religion from the state. The establishment clause.

With rights comes the responsibilities to use them.

Last lines, p434

In every country, we should be teaching our children the scientific method and the reasons for a Bill of Rights. With it comes a certain decency, humility and community spirit. In the demon-haunted world that we inhabit by virtue of being human, this may be all that stands between us and the enveloping darkness.