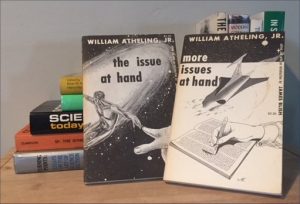

James Blish, a science fiction author who emerged in roughly the same era as Damon Knight (they were born a year apart in 1920 and 1921 and both began publishing notable fiction in the early 1950s), wrote critical essays about SF in the 1950s and 1960s that eventually were collected in two slim volumes, THE ISSUE AT HAND and MORE ISSUES AT HAND, both published by Advent:Publishers as Damon Knight’s IN SEARCH OF WONDER was, the books long regarded as counterparts or companions to Knight’s influential volume. Blish was not as prolific a commentator as was Knight, but his approach was similar in many ways: he insisted on scientific veracity and on literary standards. If anything, Blish was more persnickety than was Knight. In these books Blish frequently opines how certain habits of storytelling had by his time become established as most effective, and any variation from those habits were errors that needed to be fixed. Thus, for example, he has trouble with Frank Herbert’s DUNE because of its switching from one character viewpoint to another, a technique he understood to be not as effective a storytelling technique and single point of view. And he hoped Herbert would figure this out and become a better writer.

James Blish, a science fiction author who emerged in roughly the same era as Damon Knight (they were born a year apart in 1920 and 1921 and both began publishing notable fiction in the early 1950s), wrote critical essays about SF in the 1950s and 1960s that eventually were collected in two slim volumes, THE ISSUE AT HAND and MORE ISSUES AT HAND, both published by Advent:Publishers as Damon Knight’s IN SEARCH OF WONDER was, the books long regarded as counterparts or companions to Knight’s influential volume. Blish was not as prolific a commentator as was Knight, but his approach was similar in many ways: he insisted on scientific veracity and on literary standards. If anything, Blish was more persnickety than was Knight. In these books Blish frequently opines how certain habits of storytelling had by his time become established as most effective, and any variation from those habits were errors that needed to be fixed. Thus, for example, he has trouble with Frank Herbert’s DUNE because of its switching from one character viewpoint to another, a technique he understood to be not as effective a storytelling technique and single point of view. And he hoped Herbert would figure this out and become a better writer.

Blish’s first book, THE ISSUE AT HAND (first edition 1964; I have the second 1973 edition) focuses on magazine short fiction, in contrast to Knight’s focus on books. The essays range from 1952 to 1962. He begins with an essay of ‘propositions’ – that SF needs more criticism, in order to grow; writers need to know there are certain standards of competence. He doesn’t spell these out, so much as criticize stories on various grounds that he assumes everyone understands are those standards of competence.

- He quotes Sturgeon’s definition of science fiction – “a story built around human beings, with a human problem, and a human solution, which would not have happened at all without its scientific content” – and notes that Sturgeon later explained he meant that as a definition of a *good* science-fiction story.

- He dispels the apparently then-common rumor that Jack Vance was a pseudonym for Henry Kuttner. (Kuttner did, in fact, use many pseudonyms in the 1940s and ’50s, but Jack Vance wasn’t one of them.)

- He faults a story in Astounding for its phony realism — e.g. extended descriptions of lighting cigarettes – and ‘deep purple’, by which he apparently means overwriting and writing outside one’s experience, e.g. trying to describe alien music.

- (A general issue in the book is that Blish states a problem, but doesn’t provide examples, so at this remove we can’t be certain what he’s talking about.)

In the second essay, he begins by recommending the essays of Damon Knight.

- Blish alludes that Fantastic magazine, at that time, was supposedly the ‘adult’ counterpart of Amazing, whatever that might have meant at the time. (They were a pair of magazines co-edited and co-published for another couple decades, lastly by Ted White in the 1970s.)

- Blish curiously uses, at least twice in this book, the term “space-opera” to mean a science fiction story that might as well be translated to the present, i.e. faux-science fiction. (Whereas by now “space opera” means a story actually set in space, generally an action or military story set in interstellar space and employing SF conventions like warp drives, rather than adhering to the hard-SF constraints of actual physics.)

In later chapters,

- Blish mentions ‘deus ex machina’ endings, and ‘funny-hat’ characterizations, as obsolete writerly techniques.

- He complains about the frequency, at the time, of ‘one-punch’ or surprise ending stories, with a list of authors who committed this abuse, especially Robert Sheckley.

- Or how writers merely pile one idea on top of another (van Vogt!) rather than developing any one; an exception being Damon Knight’s “Four In One.” (He compares these to Russian music on the former point, German symphonic tradition on the latter.)

- He disdains what he calls ‘naturalism’ in a story by Erik van Lhin, again without providing examples or sample passages; apparently, he meant how events were told in very plain, everyday terms, with a result he calls dreadful.

- A long essay concerns “A Case of Conscience,” the original novelette by James Blish. (Here is an essay, presumably originally bylined “William Atheling, Jr.”, that gave Blish a means of critiquing himself in secret.) He begins by discussing the general issue of whether religion would arise on other planets, and references HPL, Heinlein, and Chesterton; then discusses “Case” with mentions of precedent stories about religion, by Lewis and Bradbury (“The Man”), Boucher and Miller. In the second 1973 edition that I have, Blish provides three afterwords, commenting about the extended book version of his story once it won a Hugo Award (http://www.sfadb.com/Hugo_Awards_1959), discussing a novel by Lowndes and then, at some length, discussing Heinlein’s STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND, which he decides is ultimately about religion (though its metaphysics are shambles).

- In one essay he misses the letter columns in the magazine (of the time), and doesn’t trust the reviews of popular nonfiction by the reviewers in SF magazines.

- Has high praise for Theodore L. Thomas’ “The Weather Man” in Analog – despite its breaking Blish’s rule about not moving the POV among several characters!

- Mentions Dean McLaughlin as one of the current ‘hard SF’ writers – along with Budrys, Dickson, and Garrett. Not authors we we now think of as exemplifying hard SF.

- Criticizes “said-bookisms”.

- Wonders why British reviewers, in newspapers, are better than American reviewers. Here’s a revelation to me: according to Blish, some American papers *really did* just reprint the book jacket blurb, and call it a review, sometimes even signed by the ‘reviewer’! This must explain one of Damon Knight’s key points, that a review is not a jacket blurb.

In the final essay of this first book, he wonders about the central appeal of SF. How while SF readers are often more widely read than readers of other genres, writers of SF almost always confine their energy to SF. He cites Poul Anderson’s speech at the 1959 Worldcon, “an appeal for a unitary approach to science fiction, in which philosophy, love, technology, poetry, and the elements of daily life would all play important and roughly equal roles.”

And then Blish wonders why the popular novels of Orwell, Vonnegut, Bernard Wolfe, Aldous Huxley, and Franz Werfel have not attracted more readers to genre SF. His conclusion: because most genre SF is about technical things; those books were about things that mattered–the relationship of the individual to the state; about power for its own sake; about what people do when technology replaces their jobs.

He cites Childhood’s End and More Than Human as SF that has such conviction. And is dismayed by recent Hugo nominations. Good SF is not about comfort and safety. “It is precisely the science-fiction story that rattles people’s teeth and shakes their convictions that finds its way into the mainstream” And so, he urges (in 1960!), that his reader vote in the Hugos, and think about each title, and ask, is it about anything??

—

The second book, MORE ISSUES AT HAND, consists of material first published mostly in the mid-1960s, with a couple essays going back to 1957 and one from as late as 1970. These focus more on novels than on the short fiction of the first volume. Highlights:

- The intro discusses various types of critics: the evaluative critic, the impressionist critic (which is all about how a work makes the critic feel), and the technical critic, who attempts to identify what makes a work go wrong. Citing Frank Herbert’s multiple viewpoints.

- Describes how SF, in 1965, has become a literary movement, not just a category of commercial fiction: the movement defined by the existence of histories and bibliographies, of critics and critical journals, of professional organizations, of awards, of specialized publishing houses. [ It strikes me that there has been more of this institutionalization of the science fiction than there has been in any other literary genre, including the “mainstream” – in fact, in this way SF is more like science itself. ]

- He reviews, in 1965, the extant critical literature of SF, just five books: Damon Knight’s; his own first book; Sam Moskowitz’s EXPLORERS OF THE INFINITE, despite its numerous errors; THE SCIENCE FICTION NOVEL (discussion here http://www.markrkelly.com/Blog/2017/12/22/sfnf-the-science-fiction-novel/); and Kingsley Amis’ NEW MAPS OF HELL. (He mentions OF WORLDS BEYOND (discussion here http://www.markrkelly.com/Blog/2017/12/20/sfnf-eshbach-of-worlds-beyond/) and L. Sprague de Camp’s SCIENCE FICTION HANDBOOK in passing [its revised edition will be the next book I cover here].)

- On Moskowitz, he describes how Moskowitz attributes ‘influence’ between authors based solely on the literal publication date of stories, even as close as a month apart, without understanding the lead-time of publications, or without knowing if later authors had ever read the earlier ones, which he might have tried to find out.

- A long essay on Heinlein from 1957 admires his use of either a single POV or a 1st person POV, with a 1967 afterword considering subsequent novels, and noting how Heinlein’s apparent political conservatism clashed with the liberal trend of most SF.

- Blish greatly admires Algis Budrys and ROGUE MOON, a masterpiece.

- An essay about Sturgeon, adapted from the special F&SF issue on Sturgeon; how Sturgeon does not write about wheeler-dealers, as do so many other SF authors, how rather he writes about love, with a love of language. Calls Sturgeon “the finest conscious artist science fiction has yet had.”

- Wonders why A. Merritt’s awful novels are so popular, with a sample passage supplied by an admirer. Blish: “The prosecution rests.”

- Discusses John W. Campbell’s current obsession – in 1957 – with psi, and notes that how psi, if it existed, would undercut the entire purpose of fiction. An aside notes that some authors, like Lester del Rey, made a point of concocting a new ‘explanation’ for space drives, or psi, each time they wrote a new story.

- And in this same essay he admires Carol Emshwiller’s “The Hunting Machine,” despite his distaste for “lady authors.” He even says “Mrs. Emshwiller is not a lady author. She is an author, period.” [ Dangerous distinction! ]

- A chapter on ‘translations’ by which he means stories that might as well be set in the present. And about ‘science-fantasy’ with its lack of respect for facts, considering Brian Aldiss’ “Hothouse” stories. Discussion of how many SF writers perceive only woe in the consequences of new technology – and so how they don’t mind being wrong about known facts. Bradbury’s Mars. Aldiss.

The final chapter, from 1970, is about the term “speculative fiction,” how SF is often judged by its worst examples, and how the Hugos are not reliable judges of the best SF (because e.g. that Vonnegut’s THE SIRENS OF TITAN didn’t win).

And then he discusses the “New Wave” of science fiction’s late 1960s, which he characterizes thusly: emphasis on problems of the present; emphasis on manner of telling; claims that this is the direction SF must go. And a few worthy stories among it all.

He discusses the various advocates and examples of New Wave writers, with special attention to Judith Merril, who wrote a few stories and novels but was best known by the mid-60s as the editor of a series of “Best of the Year” anthologies, beginning in 1956 and ending in 1968. Blish/Atheling’s take is that Merril began (like Moskowitz) as a reader exclusively of SF, with no knowledge of general literature, or of science. As she went on, she discovered literature – and so her anthologies became more and more idiosyncratic, including pieces by mainstream authors, ordinary satire, comic strips and cartoons. She embraced the term “speculative fiction” (over “science fiction”) and later the “New Wave” because they exonerated her from any implication of an obligation to understand science. Also: how she submitted, in the early years with Simon & Schuster, many more stories than could be used, and how the publisher at S&S made the final selections.

Finally, Blish discusses the prominent New Wave authors. Ballard, whose stories seemed to be forming a mosaic on some topic that even he may not be aware of. Aldiss, Brunner, Moorcock, Ellison. Zelazny and Delany and their “mytholotry” – Blish finding Delany nearly unreadable, more sympathetic to Zelazny. And he concludes by discussing Aldiss’s BAREFOOT IN THE HEAD at length, with its allegiance to James Joyce [an interest of Blish’s]. Among its themes: “the biological hypothesis that modern man is stuck with equipment (particularly mental equipment) which served well enough in the Neolithic Age but is of increasingly less use as man’s world multiplies in complexity.” (Which is a very contemporary observation.)

And Blish ends by noting that the New Wave is pulling itself apart, with all these writers going off in their own directions. (As they did.)