THE WINDS OF CHANGE AND OTHER STORIES, published in 1983, is the 11th of 14 collections of SF and fantasy stories from the ‘main sequence’ of Asimov’s collections: the set of his collections that don’t overlap, that don’t consists of remixes of stories from earlier books, that don’t consist of mystery or other non-fantastic stories, and aren’t small press or limited-edition volumes (which overlap the main sequence in most cases anyway).

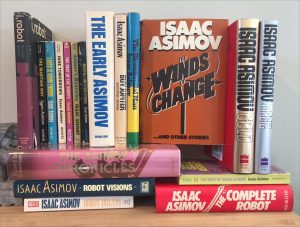

To clarify and stipulate: I’m missing one of the 14, the 1988 volume AZAZEL, fantasy stories about a pocket demon, which is why it’s not shown in the photo here. I’m missing at least one large remix, a 1985 Tor volume called THE EDGE OF TOMORROW. Other remixes are the ones shown flat in the photo. I’m not including the three early FOUNDATION books, since they are commonly thought of as novels (even though their contents were originally published as magazine stories); yet I’m including I, ROBOT, as a story-cycle that’s always been published as a collection.

To clarify and stipulate: I’m missing one of the 14, the 1988 volume AZAZEL, fantasy stories about a pocket demon, which is why it’s not shown in the photo here. I’m missing at least one large remix, a 1985 Tor volume called THE EDGE OF TOMORROW. Other remixes are the ones shown flat in the photo. I’m not including the three early FOUNDATION books, since they are commonly thought of as novels (even though their contents were originally published as magazine stories); yet I’m including I, ROBOT, as a story-cycle that’s always been published as a collection.

As with the collections of Ray Bradbury, the early volumes contain the author’s strongest work, peaking in Asimov’s case with NIGHTFALL AND OTHER STORIES in 1969. The later books, especially THE BICENTENNIAL MAN, have the occasional stand-out story, but for the most part consist of lesser works written on request, often to address a given theme, while Asimov was preoccupied with writing novels or nonfiction books. The final two collections, GOLD and MAGIC, published after Asimov’s death in 1992, are SF and fantasy respectfully, all the stories not already collected; but there were so few of them in the last decade of his life that each book is filled out with a generous allotment of essays.

The last collection before Asimov’s death in 1992 was this one, THE WINDS OF CHANGE, consisting mostly of stories first published from 1976 to 1982, with two others from the 1950s that for whatever reason were missed in earlier collections. Those two, and a couple three of the later stories, are especially interesting.

\\

A few of the lesser ones first, interesting mostly because Asimov provides short introductions to the stories that reveal why they were written, and you can see how Asimov responded to an assigned task. Asked for a story about dependence on computers, he wrote “A Perfect Fit” (1981), about an attempted computer fraudster punished with a psychologically instilled inhibition against using computers, rendering him unable to function in his modern world. It’s essentially a rewrite of Knight’s “The Country of the Kind” or Silverberg’s “To See the Invisible Man.” Inspired by his membership in a Gilbert & Sullivan society, Asimov wrote “Fair Exchange?” (1978), a time travel paradox story about retrieving the lost music from the early operetta “Thespis.” Asked for a story by a fashion magazine (!), Asimov produced “For the Birds” (1980), in which a fashion designer visits a space station and realizes that exercise in zero-G shouldn’t involve wings, but rather fins like dolphins. Asked for a four-part story for newspaper syndication, Asimov wrote, in 1979, “It Is Coming,” in which Multivac – Asimov’s cavern-sized mainframe that runs the world, from his early robot stories – is summoned to decipher the message from an approaching alien object, with a payoff about contact not between alien races, but between computers.

Given the title “The Last Shuttle,” we have a story (1981) about a much-advanced space shuttle, 170 years in the future and operating with anti-grav, ferrying away the last of the entire population of humanity, in order to leave Earth to return to wilderness. Hmm, would that really happen? Asimov can be glib at times and carry you along with persuasive arguments and counterarguments that hide the implausibility of the key premise. In “Nothing for Nothing” (1979, inspired by the idea of cave paintings) alien explorers to Earth 15,000 years ago find cave paintings of the era so remarkable they carry out an ‘exchange,’ in a curious variation of Trek’s prime directive; but really, why is idea of representational art so novel to them? And in “To Tell at a Glance” (full version original to this book) a tour guide on one of a dozen worlds in Lunar Orbit must detect which of five visitors from other worlds is possibly a saboteur from Earth. The key slip-up depends on the architecture of the worlds – toroidal space stations – and what the phrase “the other side of the world” means in that context. But would someone from Earth, hearing that phrase, automatically look *down*? Really?

\\

On to the better, or at least more interesting for one reason or another, stories.

“Belief” is a 30-page story from 1953 Astounding, and concerns Roger Toomey, a physicist who discovers he can literally levitate, as he demonstrates to his wife. He hesitates to reveal his talent to others, because as a physicist he can’t conceive how such a thing could be possible. So what does he do? He writes letters to prominent physicists at other universities, asking for their speculation on how levitation might theoretically work. His own department head learns of these letters and admonishes him. He meets with a psychiatrist for an interesting discussion of what Toomey’s *real* problem is: getting scientists to study something they don’t want to.

The story ends as Toomey attends a seminar by a fellow physicist who didn’t respond to his letter, and demonstrates levitating before his eyes, forcing him to accept the phenomenon rather that admit he might be insane.

Now, the story is contrived in that Toomey could have avoided all his troubles by demonstrating his talent to his department head and other associates in the first place. But key to this story is that Asimov mentions, in his intro to the story, that Astounding editor John Campbell – notorious for his interest in the 1950s and ‘60s in various pseudo-scientific phenomena, beginning with Dianetics (later Scientology) – forced some changes to the story that Asimov didn’t entirely approve of. Hmm. How to get scientists to study something they don’t want to. (Asimov mentions he didn’t have the original ms. of the story to use for this book.) One can see Campbell skewing the story to make that point. Trouble is, as with the Dean Drive and Campbell’s other hobbyhorses, all it takes to interest the scientist is a presentation of unambiguous evidence of a new phenomenon, and that never happens with perpetual motion machines or the like, just as this story is prolonged by the needless withholding of such evidence. There’s not really a problem here.

\\

A newer story, from 1976, is “Good Taste” (1976), set on the same orbiting Worlds used in the later story “To Tell at a Glance,” though with much more flare. Set on Gammer (a corruption of Gamma), the family of Chawker Minor welcomes him back from a year-long ‘Grand Tour’ of other worlds, a youthful practice tolerated if not approved of. The parents are Elder Chawker and Lady Chawker, the older brother is Chawker Major, and everyone in Gammer lives off ‘Prime,’ a culture of fungus, which is flavored through elaborate artificial flavors with names like Frisking Lamb, Sour-Mind, and Mountain-Tang. Minor’s older brother Major is quite skilled at this, and intends winning an annual taste competition, but Minor has some ideas of his own as a result of his tour, and enters the Finals against his brother.

The payoff recalls an Arthur C. Clarke story about artificial foods vs. their real counterparts, but what’s notable here is the amount of inventiveness in the depiction of this in-grown world and how outside worlds are held in disapproval. “Elder thinks that all rights and wrongs were written down by the makers of Gammer and that it’s all in a book of which there is only one copy and we have it, so that all the Other Worlds are wrong forever.” There’s more imaginative social speculation in this story than in the entire rest of the book.

\\

“Ideas Die Hard” is a 1957 story from Galaxy magazine, edited by Horace L. Gold, whom Asimov notes was an “acerbic individual” notorious for cruel rejections; Asimov eventually stopped submitting to him. The set up of the story is that three earlier unmanned probes sent to see the Moon’s far side have failed before reaching it, so now two astronauts are being sent on the latest probe. As they travel Davis, a contrarian, challenges Oldbury for proof that the Earth is really round, that it’s really billions of years old, and so on, or whether any evidence one might cite could have been fabricated somehow. (It recalls the Bradbury story about the astronaut who begins to doubt the existence of reality outside the ship.) Which makes it astonishing that when the probe rounds the Moon the two astronauts see – scaffolding. The Moon is a fake, a construct. There’s a surprise ending beyond that, that recalls the famous debut episode of Twilight Zone. Thus the story never truly addresses the epistemological issue: how do we know what we know, accept or challenge convention truth. The unintentional irony of the story is that it never answers its initial question.

\\

“The Last Answer” was written for the 50th anniversary issue of Analog (formerly Astounding) in 1980, in honor of editor John Campbell and Asimov’s early career there. The title sounds like a cheeky riposte to Asimov’s famous story “The Last Question,” and both deal with god issues. In this story atheistic physicist Murray Templeton dies of a heart attack and is amazed to find himself still conscious, apparently drawn into ‘heaven’ and speaking with an entity who might as well be God. This entity describes what it wants from Templeton, and how Templeton will have all eternity to fulfill that purpose. Templeton argues and draws the entity into an admission of what all eternal entities must want. As with so many Asimovian dialogues, it’s persuasive from point to point, but at the end you might suspect you’ve merely been argued into a corner.

\\

“The Winds of Change” (1982) is something of stunt, even a tour-de-force, in that except for a few paragraphs at the beginning and a few at the end, it consists of a long monologue by one Jonas Dinsmore, a mediocre college professor, directed at his department chairman and a rival, more talented, professor. Dinsmore knows he’s not liked, but while the three of them sit in a lounge awaiting some forthcoming message, he indulges himself by imagining how he might change things to his own advantage. Not by changing himself, or by changing them, or by changing the science they are all devoted to – but by changing the world around them. To turn the tables.

Furthermore, he claims, he’s concocted a means of time travel to make a change in the past to effect such a change in society. He’s researched their pasts and knows their early involvements in free thought movements.

The story’s not about how he managed time travel; it’s about what possible change he could have made to disadvantage the talent and expertise of his colleagues, their interest in science and free thought.

(Spoiler!) The message arrives, via agents of the Legion of Decency (!), who first arrest the chairman and rival professor “in the name of God and the Congregation for the crime of deviltry and witchcraft.” And then acknowledges Dinsmore as the new president of the university.

Dinsmore has his victory. Except that — final line — “In the grip of the Moral Majority, he must remember, no one was ever truly safe.”

And so scientists become victims of a theocracy. The story reflects Asimov’s concern about movements like the Moral Majority (what the Christian evangelical movement was called at the time), expressed in many of his essays of the time, along with his concern about the various forms of science-denial that plague us today, but have always been present throughout American history.