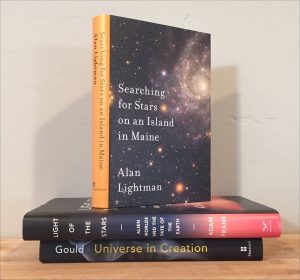

Alan Lightman is the best known of the three authors reviewed today; he’s published numerous books before, including the novels EINSTEIN’S DREAMS and THE DIAGNOSIS, as well as numerous volumes of essays, out of all of which I’ve only read a couple. SEARCHING FOR STARS ON AN ISLAND IN MAINE (Pantheon, 2018) is a book of linked essays, or reminiscences, on the themes of science and religion and the yearning for meaning. Several sections are inspired by his summers on an island off the coast of Maine, watching bugs, hummingbirds, looking at the stars. So there’s an E.O. Wilson naturalist’s flavor here.

Alan Lightman is the best known of the three authors reviewed today; he’s published numerous books before, including the novels EINSTEIN’S DREAMS and THE DIAGNOSIS, as well as numerous volumes of essays, out of all of which I’ve only read a couple. SEARCHING FOR STARS ON AN ISLAND IN MAINE (Pantheon, 2018) is a book of linked essays, or reminiscences, on the themes of science and religion and the yearning for meaning. Several sections are inspired by his summers on an island off the coast of Maine, watching bugs, hummingbirds, looking at the stars. So there’s an E.O. Wilson naturalist’s flavor here.

It’s a book of lovely writing, wise reflection on the protocols of nature and science, and mushiness about how the evidence of reality isn’t ‘meaningful’, and how there must be something *more*.

The first longish section is called “Longing for Absolutes in a Relative World,” and contrasts the scientist’s materialist views with what he says is the allure of Absolutes: “ethereal things that are all-encompassing, unchangeable, eternal, sacred.” These are ideas that have been around since antiquity, and cannot be proved or disproved, he says, though some have been given up, e.g. the notion that the Earth is not fixed.

–My reaction, that I wrote down at the time, only 17 pages in: Hopelessly mushy. What he’s really describing is the way our human nature relies on and imagines such ideas, even when as he admits they don’t exist in the simple-minded way the ancients believed, let alone in the sophisticated way we currently understand the universe. He’s too preoccupied by what those ancients (and later in the book various classics authors) supposed; we are now in a position to know better, and identify the reality our biased human nature isn’t inclined to perceive. Yet humanity in its aggregate really does learn new things, verifiable new things, even as only a very few pay attention.

Returning to a summary. He ponders how there must be more than “Just atoms and molecules”. [Why? My favorite analogy is that he doesn’t make the same argument about how the greatest books in the world can’t be merely arrangements of just 26 letters; where does the wisdom come from? There must be something *more*.] He recalls Galileo, Aquinas, Kepler, Bruno, Emily Dickinson, Lucretius.

He cycles back and forth: he understands how humans feel the need to see patterns, and that any claims from prophets be subject to the experimental testing of science — but then claims that “the transcendent experience is the most powerful evidence we have for a spiritual world.” [ Whose transcendent experiences, I wonder; those of any number of murderous psychotics one might cite? Transcendent experiences are irreproducible anecdotes, not evidence. ] He describes the central ‘doctrine’ of science but then claims there are realms in which that doctrine does not apply. How does he know? The Central Doctrine must be accepted on faith, he says. No, no, no; it’s not faith, it’s confidence, based on all the evidence to date, and always subject to revision. But, like Gould in the previous book, Lightman *wants* there to be something more.

And so on. He wends his way through Starry Night, Einstein, how we’ve deduced there are billions of other planets. He reads the Harvard Classics, Augustine, Kierkegaard, discusses the expanding universe, the multiverse, fine-tuning. (Again, overlapping topics with the previous two books.) The multiverse would be an Absolute.

He ends with a relatively homely anecdote about connecting with his kids via Facetime, pondering Homo techno and Bacon’s New Atlantis, and (Harari-like) speculation on human cybernetics. Why do people resist the idea of evolution, he wonders; species chauvinism. And the sacred books, which so many cannot let go of. Anything humans do is natural. The dignity of our species may be the final Absolute.

\\

A frustrating book. Like the maundering of a wise professor who is lapsing into self-indulgent senility. The book can be taken as an example of how naive human perception of the universe persists despite the rigor of logic and evidence. He may as well be arguing for the simplicity of belief in a flat earth, because it’s easier to understand, more comforting.

At best, this is a nice walk-around of modern ideas about how science works and what humans have learned about the universe as observed through evidence; and how, in counterpart, these revelations upset the ways humans have understood their surroundings as projections of human biases and values.

The classics of that Harvard bookshelf offer deep insights into the naïve way humans have viewed the world. They are historical artifacts. They do contain, in fact, many deep insights — into human nature (I especially recommend Montaigne). But to need to take them into account now, to assess our best understanding of the world and the universe, is like asking freshmen for their opinions to give them equal weight to the learned professors.

\\

P.S.: On page 15 Lightman cites sociologist Elaine Howard Ecklund about how 25 percent of scientists at elite universities believe in God. No; Jerry Coyne has debunked this. Ecklund is funded by the religiously motivated Templeton Foundation, and she is biased toward simplifying a range of results into bins that most support its mission. Here’s an example: Ecklund and Long: Scientists are totally spiritual. An object lesson in how to ask a question and how to tally the results, and motivated reasoning. (Others)

Similar comments could be made about Christian apologist Alvin Plantinga, whom Lightman cites on page 121.