Bradbury, SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES (1962)

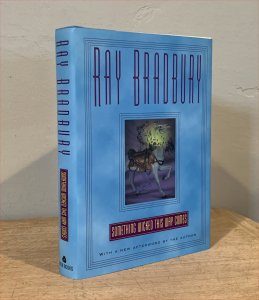

When I read or reread some two dozen Ray Bradbury books three years ago, in January and February 2018, I skipped this 1962 novel (despite it being one of only two genuine novels written to that date, or perhaps the only one, since the other of the two was an expansion of an earlier novella), because I was reading Bradbury for his fantastical takes on science fiction themes, and this novel is about as pure fantasy as you can get. But I finally picked it up a couple weeks ago and read it through. (Using the 1999 Avon hardcover edition shown here.)

When I read or reread some two dozen Ray Bradbury books three years ago, in January and February 2018, I skipped this 1962 novel (despite it being one of only two genuine novels written to that date, or perhaps the only one, since the other of the two was an expansion of an earlier novella), because I was reading Bradbury for his fantastical takes on science fiction themes, and this novel is about as pure fantasy as you can get. But I finally picked it up a couple weeks ago and read it through. (Using the 1999 Avon hardcover edition shown here.)

It’s the ultimate evil circus story. It contains Bradbury’s most effusive, poetic language. And I found the thematic core of the novel, discussed over just five pages about two thirds of the way through, fascinating and compelling enough to type out several paragraphs to post here.

Outline and Quotes:

Part I

- Set in Green Town, the setting of Dandelion Wine, it’s about two boys, James Nightshade, brown-haired, and William Holloway, blond, both almost 14. Will is more brash; James more brooding, and James’ father has died. William’s father, Charles, is a night janitor at the town library.

- The boys meet a lightning rod salesman, Tom Fury, just as posters for a circus, or carnival, start appearing around town.

- One night after midnight a train chugs through the town, and the two boys run to watch it pass, and see it stop in a meadow outside town. A big balloon brings the proprietor; men work in silence setting up tents.

- The next morning the boys wonder if it was a dream; no, it’s still there. They find Miss Foley, their 7th grade teacher, there, looking for her nephew, who has just arrived. Did he go into the mirror maze? The boys warn her not to go in. But she does, and sees someone, her younger self.

- Jim gets lost in the maze, and Will pulls him out.

- They find the lightning-rod salesman’s bag, but not him.

- They watch a merry-go-round go round, and the two men who run the carnival, Mr. Dark (who is the Illustrated Man) and Mr. Cooger. The latter boards the carousel as it goes *backwards*, playing odd music, and they watch his face melt, getting younger, all the way back to age 12.

- They follow this boy to Miss Foley’s house—she thinks this boy, actually an adult, is her nephew Robert.

- That night the boys sneak out and go to Miss Foley’s house, and call to the boy, who senses that Jim wants to use the carousel to get older. He chases them off by tossing Miss F’s jewelry onto the lawn, as if framing them for theft.

- All three run to the carousel, fighting; the switch box blows and the boy Robert becomes an old man, maybe 120. He’s cold, but alive. The other two boys flee, calling police and ambulance; but when they arrive the old man is gone. They go into a tent full of freaks, where Tom Fury has been turned into Mr. Electrico, a new act. The old man is there, alive, and explains the incident away to the policeman, who smile knowingly as if this is all just another boyish prank.

Part II

- The boys have to make a police report. Later they reflect on how good people and happy people aren’t the same.

- A balloon passes over, carrying a Dust Witch, which drops a slimy trail over their houses. They go out to wash it off. Then they lure the balloon to an empty house, and throw an arrow at it to burst it.

- Rain falls. The boys dream of a funeral. Heading to the carnival, they find a little girl—and realize it’s Miss Foley. A parade comes through town, and the little girl is gone. The boys realize they’re being hunted and have to hide. They hide under a grate by the cigar store. Mr. Holloway meets the man with tattoos on his finger in a coffee shop. The IM appears asking about the two boys—they’ve won a contest, he claims, and need to know. Mr. H is suspicious enough to give false names.

- That night Mr. H spends hours researching through mounds of books. The boys come to the library and now tell their entire story to Mr. H.

- Mr. H in turn tells them what he’s learned. That the carnival was here in 1888. And 1860, and 1846. Always in October. He recalls how some are “autumn people.” Where do they come from?

- Mr. H cautions they don’t have to stay foolish, or be sinful. There’s fear on both sides. He goes on… (Here’s is Bradbury’s theory of good and evil, and of civilization, p195-196 in hardcover Avon edition.)

If men had wanted to stay bad forever, they could have, agreed? Did we stay out in the fields with the beasts? No. In the water with the barracuda? No. Somewhere we let go of the hot gorilla’s paw. Somewhere we turned in our carnivore’s teeth and started chewing blades of grass. We been working mulch as much as blood, into our philosophy, for quite a few lifetimes. Since then we measure ourselves up the scale from apes, but not half so high as angels. It was a nice new idea and we were afraid we’d lose it, so we put it on paper and built buildings like this one around it. And we been going in and out of these buildings chewing it over, that one new sweet blade of grass, trying to figure out how it all started, when we made the move, when we decided to be different. I suppose one night hundreds of thousands of years ago in a cave by a night fire when one of those shaggy men wakened to gaze over the banked coals at his woman, his children, and thought of their being cold, dead, gone forever. Then he must have wept. And he put out his hand in the night to the woman who must die some day and to the children who must follow her. And for a little bit next morning, he treated them somewhat better, for he saw that they, like himself, had the seed of night in them. He felt that seed like slime in his pulse, splitting, making more against the day they would multiply his body into darkness. So that man, the first one, knew what we know now: our hour is short, eternity is long. With this knowledge came pity and mercy, so we spared others for the later, more intricate, more mysterious benefits of love.

So, in sum, what are we? We are the creatures that know and know too much. That leaves us with such a burden again we have a choice to laugh or cry. No other animal does either. We do both, depending on the season and the need. Somehow, I feel the carnival watches, to see which we’re doing and how and why, and moves in on us when it feels we’re ripe.

And page 198:

Have I said anything I started out to say about being good? God, I don’t know. A stranger is shot in the street, you hardly move to help. But if, half an hour before, you spent just ten minutes with the fellow and knew a little about him and his family, you might just jump in front of his killer and try to stop it. Really knowing is good. Not knowing, or refusing to know, is bad, or amoral, at least. You can’t act if you don’t know. Acting without knowing takes you right off the cliff. God, God, you must think I’m crazy, this talk. Probably think we should be out duck-shooting, elephant-gunning balloons, like you did, Will, but we got to know all there is to know about these freaks and that man heading them up. We can’t be good unless we know what bad is, and it’s a shame we’re working against time. Show’ll close and the crowds go home early on a Sunday night. I feel we’ll have a visit from the autumn people, then. That gives us maybe two hours.

- And so who are they? Perhaps they began with one man, “stuffing himself with other people’s unhappiness,” who attracted more like him. “The stuff of nightmare is their plain bread.” They drove slaves to build the pyramids, they plotted against Caesar. They became gypsies, acquired a train. But why do they hurt? “Because you need fuel, gas, something to run a carnival on, don’t you?” Gossip, pleasure at funerals and at obituaries. “All the meanesses we harbor, they borrow in redoubled spades….”

- So what do the three of them now do? Burn in down? Mr. Dark finds them, offering Mr. H youth for his help—otherwise Mr. Dark can induce a heart attack. He crushes Mr. H’s hand, and takes the boys. The Witch comes in to stop Mr. H’s heart—but he laughs! And she flees.

Part III

- The boys are marched into the carnival. They will travel with them too. They are stood among the wax figures. Mr. Dark will perform the bullet act for the crowd (in which he fires a fake bullet and the witch pretends to catch it in her teeth). He needs a volunteer. Mr. H volunteers!, and in turn requests one of the boys to volunteer. Will manages to respond, helping his father carve a symbol on the phony bullet, a symbol like a smile. And so when the shot is fired, the witch falls over dead. Mr. Dark abruptly halts the show.

- And so on: Mr. H uses the power of laughter to kill Mr. Dark, and when Jim rides the carousel and falls off, Mr. H encourages Will to sing and laugh with him, reviving Jim back to life.

The Wikipedia post about this book is very thorough.

Comments

It’s curious that Bradbury suggests that gossip is the root of all evil. In fact recent ideas about the evolution of social groups in human history suggests that gossip is useful, even crucial, as a means of monitoring the moral status of members of the tribe. (Once tribes become communities and towns, where gossip can’t keep track of everyone [the limit for any one person seems to be about 150], laws and regulations take over.) Actually, I suppose, he doesn’t implicate gossip itself, so much as the pleasure people take in learning about the misfortunes of others (schadenfreude).

And the main point of the second big quote above is that compassion and understanding come from getting to know other people, especially others not like yourself. This is why, compared to small rural towns, people who live in big cities, those that are melting pots of people from many cultures, or as in port towns where the residents encounter people from other cultures, tend to be more liberal, and arguably more compassionate.

And I appreciate the general theme that civilization, that mercy and compassion, arose from knowledge, from being aware of life and death. And that acting morally depends on knowledge. That “not knowing, or refusing to know, is bad.” Applies to all sorts of science denial in our modern age.