This week’s Sunday novella is “Oceanic” by Greg Egan. It was first published in the August 1998 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction.

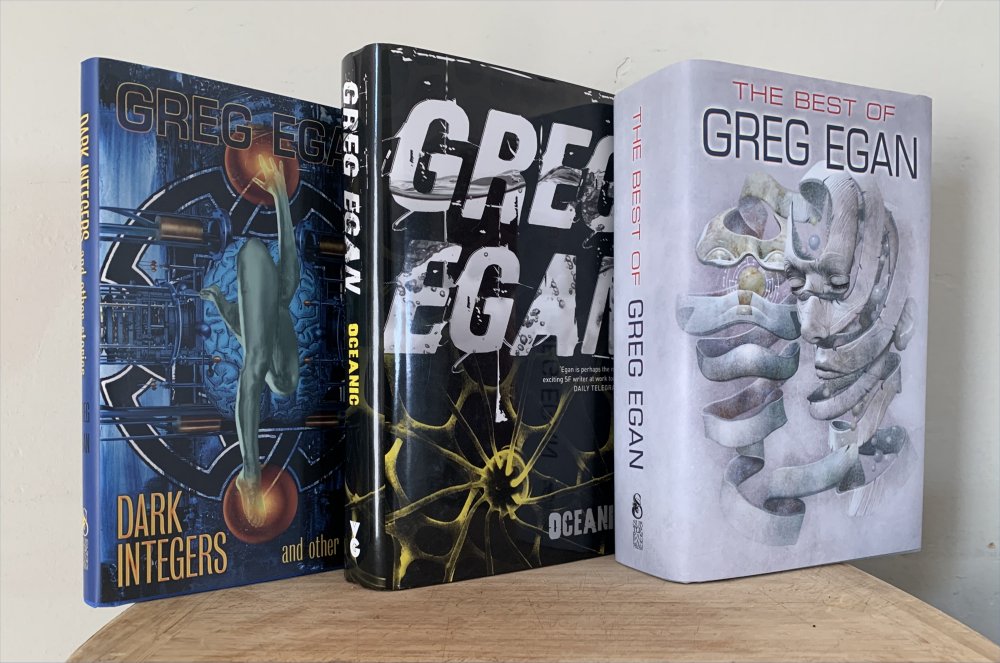

Subsequently it’s been published, aside from in these Dozois anthologies, in the author’s collections Dark Integers and other stories in 2008 and Oceanic in 2009, the former in the US and the latter in the UK, and then in The Best of Greg Egan in 2019 in the US.

Egan is perhaps science fiction’s greatest mystery man. He does not attend conventions, he does not appear in public, he does not release photographs of himself. He lives in Perth, Australia.

He is likely the hardest of hard science fiction writers ever. He maintains a substantial website, https://www.gregegan.net/, with synopses of most of his works, and in many cases with technical background on his works including complex diagrams and equations. (To link such a page at random: Incandescence: Deriving the Simplest Geometry.) He has remained moderately prolific over three decades, though a couple of his recent books are self-published, or published in pricey limited editions (from Subterranean Press). My impression, without having kept up with all of his works, is that the novels of the past decade or so (since The Clockwork Rocket in 2011) have become increasingly abstruse in that they invent worlds or universes operating to different physical principles than our own. Tough going even for a reader savvy in physics.

He won a Hugo Award for the story discussed here, and won a John W. Campbell Memorial Award for his 1995 novel Permutation City. He’s placed on the Locus Poll dozens of times, winning three times, including for “Oceanic,” and has eight other Hugo nominations. He’s never been so much as nominated for a Nebula Award, nor has he ever been shortlisted for the Arthur C. Clarke Award.

His page for this story links to the complete text of the story.

\\

“Oceanic” is a novella, longer than most of Egan’s shorter works, and is structured in six sections, the early ones seemingly on almost unrelated topics, until the pieces all come together at the end. The setting is the planet Covenant, whose settlers came from Earth some 20,000 years before, the details of that trip lost to myth and religion. The settlers are now divided into Firmlanders, who live on the land, and Freelanders, who live on boats at sea. The main character, Daniel, and his family are Freelanders, and their religion concerns Beatrice, the daughter of God, who led the Angels from Earth to Covenant as a place for them to repent for their theft of immorality. There are sects of this religion, the Transitionals and the Deep Church, who have different opinions about the ultimate fate of humans and Angels. And there is a baptism-like “immersion” ceremony that transcends mere faith and allows Beatrice to come directly into a person’s heart.

The story begins dramatically, as 10-year-old Martin talks with his older brother Daniel about whether he believes in God, and how the ecological evidence on the planet doesn’t align with the Scriptures that tell how humans arrived on Covenant 20,000 years ago. Daniel challenges Martin then and there to the “immersion” ceremony that involves being weighted down with rocks and lowered into the water for a count of 200. (If Egan’s prose can often be didactic, this section is extremely tense and suspenseful.) It works! — And Martin feels euphoric, and comforted, and understands how everything now is about honoring and thanking Beatrice.

Does all of this sound like a parody of Christianity? Perhaps, but it’s more of an analogy, I think, and a tribute to the autobiographical elements of the story. (More on that below.)

Subsequent sections follow Martin as he accompanies a Prayer Group to a monastery, where he testifies about his conversion. Several years later he attends his brother’s marriage to Agnes, of a Firmlander family, where he meets her cousin Lena and engages in sex for the first time — this entails exchanging a penis-like organ called a “bridge” between the two, in effect becoming each other’s gender. (What is this all about in the context of the larger story? I take it to indicate that neither their Scriptures nor their science have made the humans on Covenant aware that they’ve been genetically-modified from the original Earth stock. That reference to immorality and all the talk of Angels presumably derives from that same unknown past.)

(Spoilers follow.)

Martin goes on to study at a Firmland university, where he studies ecopoiesis and debates theology with fellow students. (Not everyone on Covenant follows Beatrice.) His faith wavers. And years after that attends a conference where his research has contributed to the discovery that something in the very water of this planet causes euphoric effects — such as, of course, the profound presence of Beatrice. He endures the shock of deconversion; everything important he’s known has been a lie.

The news becomes public and fully understood. Egan has some fun imagining reactions from various kinds of protestors, e.g. the relativists who insist it doesn’t matter, no story is greater than another, that everyone’s beliefs are “really” about (says a particular speaker) the one true god Marni.

The discovery changes Martin’s life, of course, as the story winds down fairly quickly with him coming to a kind of existential acceptance. And the end he has an encounter with a priest, and asks him, Do you believe in God? (As the story opened.) And the priest answers, “As a child I did. Not anymore. It was a nice idea…but it made no sense.” Then isn’t life unbearable? “Not all the time.”

\\\

The striking thing about the story is that it dares to suggest that religious belief is merely biochemical in nature. Hardly controversial to neurologists or even to some religious scholars. Yet many ordinary religious folks I imagine would be shocked by the notion, even finding it sacrilegious. It would get the book banned in certain US states, if it ever came to their attention.

Such ideas seldom trouble science fiction readers, of course; they are what we come to SF for. And this is a story that moves not just from childhood innocence to adulthood maturity, but from faith and tradition to enlightenment and wisdom.

\\

Doing a bit of background checking on this story, I was surprised to discover that it’s partially autobiographical: Egan himself was devout as a teenager and young man, for a while. This via Karen Burnham’s Greg Egan volume in the “Modern Masters of Science Fiction” series published by the University of Illinois Press, which points to an essay by Egan in the book 50 Voices of Disbelief: Why We Are Atheists, edited by Russell Blackford & Udo Schüklenk, published in 2009. (Among other contributors is Michael Shermer, who had a similar experience as a young adult.) Like the text of “Oceanic,” this essay is on Egan’s website as well, at https://www.gregegan.net/ESSAYS/BAB/BAB.html. It begins:

Though I have never encountered a persuasive argument for the metaphysical claims of any religion, for more than a decade — from the age of twelve until my mid-twenties — I was convinced that I had direct, firsthand, and incontrovertible knowledge of God’s existence.

\\

It’s also worth noting a key remark in Egan’s afterword to The Best of Greg Egan. Page 729:

If there is a single thread running through the bulk of the stories here, it is the struggle to come to terms with what it will mean when our growing ability to scrutinize and manipulate the physical world reaches the point where it encompasses the substrate underlying our values, our memories, and our identities.

He recalls “Reasons to Be Cheerful” (1997) in particular.

\\

Fun facts. I read “Oceanic” when it first came out, of course. And then read it again in 2016, when I discovered two books by Egan in the ship’s library of a cruise ship we were taking through the Caribbean. (Mentioned here.) So I spent a couple afternoons rereading the story while lounging by the ship’s pool.

The story by Egan that Dozois chose for his first Best of Best anthology was “Wang’s Carpets” from 1995. But the story isn’t included in any Egan collection. I tracked down why: it became a chapter of Egan’s novel Diaspora in 1998.