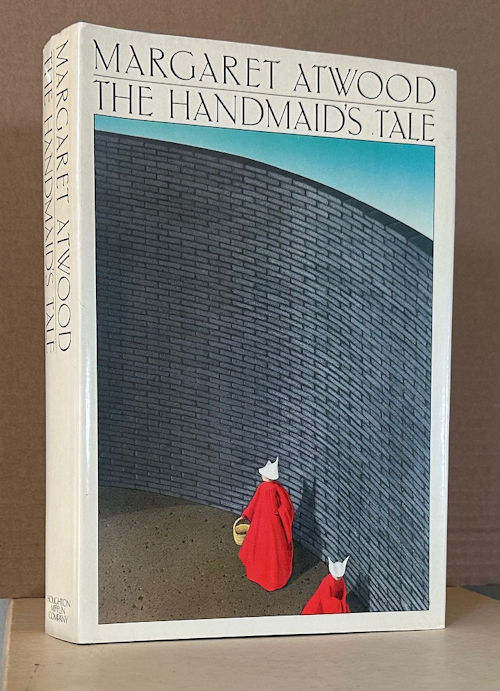

(Houghton Mifflin, Feb. 1986, hardcover, 311pp)

This is the US first edition hardcover, which I bought when it came out (it’s the first printing too), though the book was published in Canada the year before, in 1985. It’s 40 years old! It’s more than half as old as NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR!

When I sat down in June to read or reread a number of apocalyptic novels, this was the one I had first in mind, though of course it’s more of a dystopia than an apocalypse.

I read the book not long after it came out, in ’87, but its resurgence in popularity the past few years what with the 2017 Hulu TV series, and especially with the second Trump administration, with its Project 2025 premonitions of regressive social controls — including the books’ appearance on the bestseller lists that I compile every Monday for Locus Online — prompted me to revisit it.

As with a couple of the other books I’ve covered lately, it’s fair to wonder, is this ‘really’ science fiction? Where’s the science? Actually, there is some, though it’s almost incidental. As with the Orwell novel, it’s mostly about a social revolution, and some ‘mainstream’ readers don’t consider such stories to be science fiction. SF readers do; this book was nominated for a bunch of SF awards, and even won one, the Arthur C. Clarke Award (in its first year), and has been listed by almost two dozen citation references and survey. (See this sfadb page.) Ironically, Atwood herself did *not* consider the book science fiction, because she thought of science fiction as being about “squids in space” or some such. And she claimed that nothing happens in this novel that has not happened in history. In any case, she went on to write several more novels with near-future settings that have also been considered SF. And there was a sequel to this book, THE TESTAMENTS, in 2019. Which I’ll get around to eventually.

The book is well enough known, especially via the TV adaptation, that I’m not going to spend much time summarizing it. Gist: It’s set in a future in which a religious state has overthrown the US government and set up a sort of theocratic dictatorship for the sake of controlling women. The ostensible reason being that female fertility has fallen drastically. Why? Atwood isn’t particularly interested in why, but offers some vague reasons, p112:

The air got too full, once, of chemicals, rays, radiation, the water swarmed with toxic molecules, all of that takes years to clean up, and meanwhile they creep into your body, camp out in your fatty cells. Who knows, your very flesh may be polluted, dirty as an oily beach, sure death to shore birds and unborn babies.

And so on. The result is a caste system of women’s roles, in which those still fertile are “handmaids” and have the children of wealthy men whose Wives are infertile. Those men are called Commanders. Above the handmaidens are the Aunts, like the notorious Aunt Lydia. The story follows one handmaid, called Offred because her Commander is named Fred (and whose original name is not mentioned in the novel). Her daily life is ritualized, and borne by the hope that some secret society might show up to save her, to take her away. Much more detail at the Wikipedia page.

\

The novel is ‘literary’ in a way most SF novels are not in several ways. It alternates between flashbacks and the current narrative (well OK, that’s not so uncommon). It’s very subjective; we read about Offred’s experiences without always understanding what’s happening to her. There’s very little proper plot, just many incidents that we gather happen over and over. And the end is ambiguous.

\

There’s a curious epilogue called “Historical Notes,” purportedly written in 2195, looking back at that era of the Republic of Gilead, as it was called, and speculating if any of the people named in the manuscript “The Handmaid’s Tale” actually existed. (There are more allusions to toxic leaks and other causes.) Nothing definitive about any of those people. But these notes imply that Gilead didn’t last forever, perhaps not even very long. Nor was it widespread.

\

Finally, stepping out, a bit of context. The novel is held as an example of religious totalitarianism, in which a society is built that matches what some real-life Christian fundamentalists would build, if they could, and so is a warning of what could happen should those Christians get there way.

I see more to it than that. That is: morality is not fixed. We’re horrified by this Republic of Gilead, and its degradation of women as chattels and baby machines, but that’s because we live in a relatively healthy society where societies can *afford* to grant its citizens “equal rights.” But if for some reason female fertility dropped dramatically, and the birthrate fell dramatically, what would people do? Alas, Atwood focuses on just one community, without wondering if this kind of thing is happening around the world; but that’s a common failure of science fiction. Consider extreme cases. Suppose humanity were reduced to 100 men and 10 women. Would our 21st century egalitarian morality (well, excepting MAGA, who would probably approve of Gilead) still apply? Likely not. What if male fertility fell? I think Harlan Ellison considered that in “A Boy and His Dog.” These scenarios are all different settings on the sliding scales of morality.

\

And a bit about how humans survive what others look back on as atrocities. By ignoring.

Page 56:

Is that how we lived, then? But we lived as usual. Everyone does, most of the time. Whatever is going on is usual. Even this is as usual now.

We lived, as usual, by ignoring. Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance, you have to work at it.