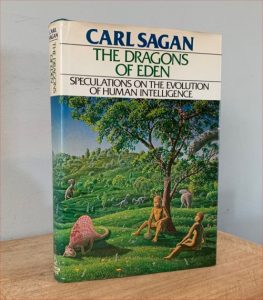

Carl Sagan: The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence. Random House, 1977.

This was Sagan’s first book since his 1973 hit The Cosmic Connection (revisited here), and is distinctive in two ways. First, it was the first solo book of his to be written through, as a book, rather than a compilation of earlier articles or an anthology of pieces by others. Second, it was on a topic adjacent to the fields he was best known for, as the subtitle indicates. He admits this in his intro, justifying his theme by suggesting how the lessons of biology, in particular evolution, can not only suggest how humanity might proceed into the future, but how this might inform his special interest: the search for extraterrestrial life (SETI).

I have the first edition and read it when it came out, then reread it a couple years ago ago after seeing it the sole Sagan title listed in an ambitious, and well-informed, book by James Mustich called 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die: A Life-Changing List (2018). (Really? This one? Not Cosmos or The Demon-Haunted World?)

I’m going summarize the book’s chapters in bullet points, because much of the material is familiar from readings in basic evolution and need not be detailed here again.

- Intro. Sagan invokes Jacob Bronowski, whose book and TV series The Ascent of Man was one of the prototypes for Sagan’s Cosmos, to suggest that we need a better understanding of the human mind to tackle current problems. And, incidentally, to understand what we might expect should we actually make contact with extraterrestrial civilizations, a particular interest Sagan’s

- Ch 1, The single most memorable take-away from the book is in the first chapter: the Cosmic Calendar. This is Sagan’s notion to reduce the entire age of the universe down to a single calendar year, and see where various key events in cosmic history took place on the calendar. And his point is that human history is just a tiny sliver of cosmic history: the last hour or two of December 31st. With the Renaissance in Europe occurring only in the last second.

- I was sure I’d heard this idea elsewhere in Sagan’s work, but it was later, not earlier. Sagan used the concept two or three times in his TV series Cosmos — envisioning the calendar as a large area inside a dark soundstage on which he could walk around — in 1980. Then, perhaps confusedly, he didn’t mention the topic in his 1980 book version of the show. Because he’d already written about it in this book in 1977.

- Ch 2 covers genes and the brain, how evolution has led to increased complexity, about the rate of mutations, and how our brains have about 10 billion neurons, each one having up to 10,000 synapses to other neurons.

- Ch 3 How the brain has evolved in layers, the oldest and most primitive at the bottom, more complex animals having newer layers at the top. Thus our “reptilian” brain at the bottom, our neocortex on top, the limbic system in the middle. All three are still in operation, often in rivalry with each other. Analogies, only very loosely, are to Freud’s system, to conscious, preconscious, and subconscious, and to Plato’s metaphor about the chariot drawn by two horses.

- Ch 4 is about the evolution of Man, with Eden as metaphor. There is speculation about which came first: walking on two legs; big brains; making tools. As intelligence evolved human babies’ heads became larger, childbirth thus more difficult. With intelligence came the awareness of death: a fall from the innocence of Eden indeed. Language may have arisen to coordinate hunting of predators. Other manlike creatures existed up to a few tens of thousands of years ago; what happened to them? [[ Harari, 40 years later, spells it out bluntly at the beginning of his first book: what became modern humanity exterminated those others. ]]

- Ch 5 is about other animals that exhibit abstract thought: chimps learning sign language, and simple tools. Were they to develop language they might experience the insight of Helen Keller’s realizes about “water.” Perhaps chimps survived because they didn’t speak, at a time early humans exterminated other primates who did.

- Ch 6 is about why most animals need to sleep, and what happened to the dinosaurs [this was before the discovery of the big asteroid or comet that hit the Earth 60m years ago]. How fire, divination by dreams, memories of reptiles (as dragons) came to form parts of the Genesis myth; dragons in Eden. Reptiles do not dream. Our limbic system came to interact with the R-complex, enabling dreams.

- Ch 7 Humans have pour sense of smell, but great sight. And we’ve developed a sense of the “intuitive” underneath our analytical skills. Why? Evidence from split brains, how each side has different skills. Reflected in the polarity of left and right, evil and good. The left side is skeptical; the right given to conspiracy thinking. [Chapter goes on with more examples, but all of this is now much better understood by experimental psychologists with conclusions about modes of thinking, perceptual biases, and so on, c.f. Haidt, Kahneman, et al.]

- Ch 8 So we understand that different human behaviors are functions of different parts of the brain. Human societies are hierarchical and ritualistic, and resist change (like mutations, changes are often harmful). But we are no longer hunter-gatherers, and the world currently is not working well; we are not still living in static societies. Understanding the brain better might help with some current issues — the definition of death; the abortion debate; the intelligence of other species (e.g. whales and dolphins) to stop slaughtering them. Drugs, similar to those in the brain, might treat mental illness, programming of automatic behaviors to control epileptic seizures, etc. Current fears about the potential of machine intelligence (with 1970s era examples) will likely lead to partnerships between humans and machines.

- Ch 9 addresses the book’s secondary theme: what can we conclude from these studies about the possibilities of extraterrestrial intelligence? Other beings might have exotic biology or politics, but would have similar understanding of physics and chemistry. And their brains? Like ours, consisting of several components accreted by evolution, their society dependent on peaceful coalition of those components, aided and extended by machines. Receiving a message from other beings would show it possible for societies to live with advanced technologies. But governments are often short-sighted, reluctant to make investments to could lead to the discovery of such messages; indeed, we seem to be experiencing a resurgence of pseudo-science and mysticism. They are limbic and right-hemisphere doctrines, while the path to the future lies almost certainly in functioning of the neocortex: “a courageous working through of the world as it really is.”

I was rather underwhelmed by the book rereading it recently, only partly because so much of it is basic and well-known. Perhaps I was expecting more speculation about the nature of alien intelligence. But he goes there only to suggest that the existence of other intelligences shows that it’s possible for advanced societies to live with advanced technology. (The idea that they can’t is one of the solutions to the Fermi paradox.) Sagan spends most of the book showing how the understanding of the brain, especially as it’s constructed of three layers, explains much of human behavior and society (and the political divide, alas). Sagan’s conclusion about the future of human intelligence is that it’s a partnership between intelligent humans and intelligent machines.

And finally:

It is only in the last day of the Cosmic Calendar that substantial intellectual abilities have evolved on the planet Earth. The coordinated functioning of both cerebral hemispheres is the tool Nature has provided for our survivial. We are unlikely to survive if we do not make full and creative use of our human intelligence.

“We are a scientific civilization,” declared Jacob Bronowski. “That means a civilization in which knowledge and its integrity are crucial. Science is only a Latin word for knowledge… Knowledge is our destiny.”