- More about conservative comments about San Francisco;

- Paul Krugman wonders why MAGA hates the planet;

- How conservatives prioritize big families: quantity over quality;

- Connecting dots between mentions of Tom Holland and his book DOMINION;

- The MAGA attitude of contempt for others, as seen recently by Pam Bondi;

- And some early Philip Glass: A Madrigal Opera.

Which locals come to take for granted, of course.

\\\

Another item about conservative hatred of San Francisco.

Salon, Sophia Tesfaye, 10 Feb 2026: Super Bowl bursts popular right-wing media myth, subtitled “Conservative commentators and podcast bros backtrack on what they’ve said about San Francisco”

I always thought the idea of San Francisco as a dystopian nightmare was some kind of bit. An exaggeration made meme, something people said with a wink to signal their politics more than their understanding of reality. I didn’t realize just how many Americans actually believe it so deeply that they could travel across the country, step off a plane and walk through one of the most visually stunning cities on the continent — only to be shocked that they were lied to.

\\\

Another item about conservative hatred of science.

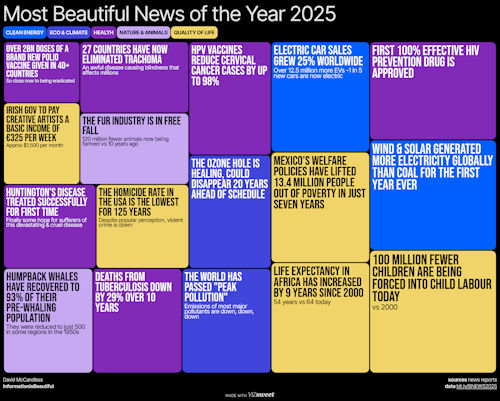

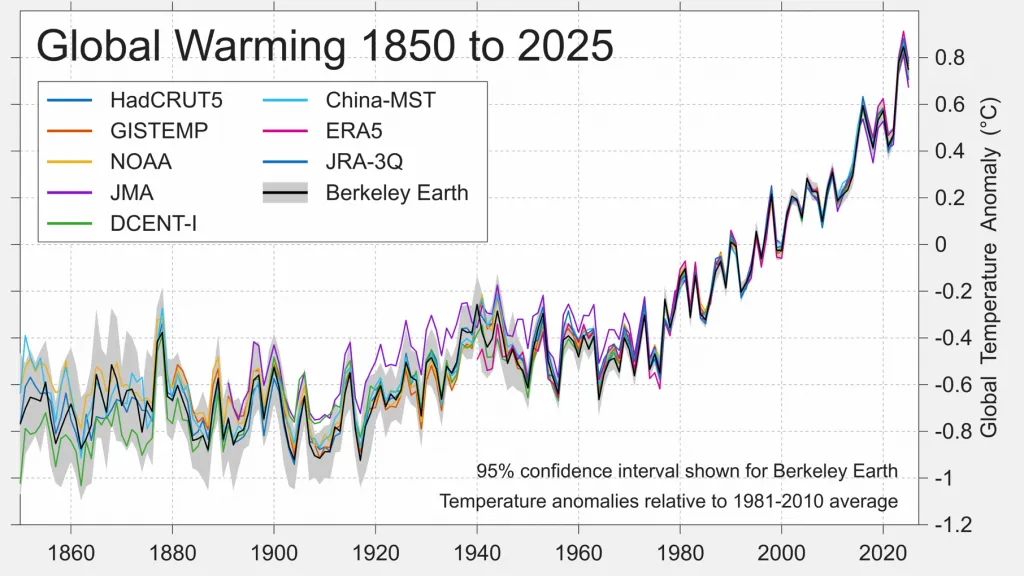

Paul Krugman, 16 Feb 2026: Turning Our Back on Clean Energy, subtitled “Why does MAGA hate the planet?”

Krugman opens by discussing recent weather events and the accelerating of climate change. Then:

…the Trump administration has gone to war against any and all efforts to limit climate change. The administration is also imposing a “blockade” against wind and solar projects, delaying or even revoking permits, whether or not these projects have received federal subsidies.

Now, there isn’t a genuine scientific dispute about the reality of global warming and its causes. There isn’t even a serious dispute about the costs of fighting climate change: the economics of green energy are more favorable than they have ever been.

So what’s going on? The Trump administration hates science and science-based policies in general; look at its war on vaccines, which will end up causing an enormous number of deaths. Its assault on universities threatens the best scientific research centers in the world. Its irrational treatment of immigrants means the best and brightest from the around the world no longer want to come here. But in the case of energy, its destructive policy largely reflects the corrupting influence of big money.

Then history about how alarm about the changing climate has been around for at least 40 years. Then to the current situation, which boils down — as I’ve noted — to the greed of the billionaires who are buying the government and getting regulations cancelled so they can make more money. And enrich the Trumps.

At this point, moreover, it’s not just about normal channels of political influence, nor it just about domestic billionaires. We now live in a time in which U.S. policy is shaped by sheer, naked corruption (enabled in part by the Koch takeover of the courts). Notably, Middle Eastern petrostates, which have a strong interest in blocking the energy transition, have played a huge role in enriching the Trump family.

\\\

Another item about conservatives’ warped morality of quantity, not quality.

Salon, Amanda Marcotte, 16 Feb 2026: MAGA loves bad dads, subtitled “Raising kids should be about quality, not quantity”

What makes someone a good father? Answers vary. Some folks might cite being hard-working or handy, but most people would likely circle around concepts of well-being and strong values. Good dads make kids feel safe and loved. They raise children with moral fiber, to care about the people in their lives as well as the larger world around them.

But MAGA media has a very different idea of how to measure the worth of a father. They believe it’s by how many kids he has produced. In this worldview, the father deserves most of the credit, despite putting almost no effort into the production side of having babies. In an era when most people can barely afford to raise one kid, this focus on quantity isn’t just tone-deaf. It reduces kids to a commodity, which in turn encourages neglectful, toxic or even abusive approaches to parenting.

Charlie Kirk. Pete Hegseth. JD Vance, Elon Musk. Stephen Miller. Trump. Mike Johnson. Others.

This morality is warped because it, presumably, is based on Biblical injunctions to “be fruitful and multiply,” an admonition that might have made sense to struggling desert tribes thousands of years ago when infant mortality was very high. It doesn’t make sense today, and is counter-productive in the long-term. (That “Quiverfull” movement is also implicated here.)

\\\

Another item about interpreting history through bias.

Three days ago my first item mentioned a book by historian Tom Holland called Dominion, which gave Christianity credit for the idea that the weak and poor deserved moral recognition. The name and title rang a bell, but I couldn’t place it. Today I did. Richard Dawkins discussed the book in this post on his Substack and I discussed his post in my post of 31 Oct 2025. The connecting theme might be that Holland takes the Bible very literally, and is biased to interpret history to give maximum credit to Christianity. Motivated thinking.

\\\

The MAGA attitude.

NY Times, opinion by Frank Bruni, 16 Feb 2026: I Hold Pam Bondi in Contempt

I imagine Pam Bondi getting ready for one of her appearances on Capitol Hill by practicing in front of a mirror. She hones her glare. She perfects her sneer. She rehearses her lines, such as they are.

“Washed-up, loser lawyer!” That’s for Representative Jamie Raskin, Democrat of Maryland. What the phrase lacks in poetry it makes up for in pithiness. It’s just four short words, two of them conveniently conjoined with a hyphen. Even Bondi can remember that much.

“Failed politician!” That’s for Representative Thomas Massie, Republican of Kentucky. Two words. Insults are all about efficiency.

But it’s not Bondi’s script that matters most. It’s her voice, and the attorney general got the tone of it — the poison in it — just right when she spat those put-downs at those men during her, um, testimony before a House panel last week. She didn’t merely ooze contempt. She gushed it, so that all she communicated during more than four hours of nasty exchanges was how loathsome she found her interrogators. Which was obviously her goal. Her mission.

MAGA has adopted the contempt that they felt the Democratic elite directed toward them. Bruni concludes:

She opted for contempt. It’s the Trumpian way. But is it the American one? Has the country sunk quite this far? I don’t think so. She and her fellow insultmongers aren’t owning the libs; they’re beclowning themselves. And it’s a repellent circus.

\\\\

Early Philip Glass. I’ve been sorting through all my Glass CDs — I think I have over 100. Using Wikipedia’s List of compositions by Philip Glass, I’ve been sorting most of them chronologically, and listening to them that way. Glassworks was the first release I became aware of, but earlier pieces were released later. Today I’m listening to a piece called A Madrigal Opera, composed in 1980 and so between Satyagraha and Akhnaten. Oddly, this is rather more basic than those two, relying more on the repetitive arpeggios, without any soaring melodies. Here’s a section from YouTube. Some of these melodies were later used in Koyaanisquatsi.