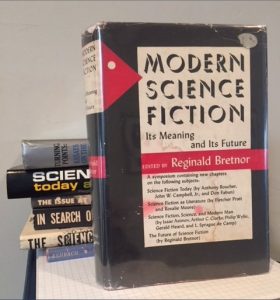

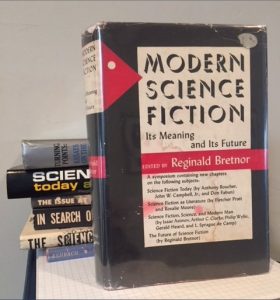

Reginald Bretnor’s 1953 Modern Science Fiction: Its Meaning and Future is one of the earliest critical volumes about SF. If follows Lloyd Arthur Eshbach’s 1947 OF WORLDS BEYOND (summarized here) and precedes the anonymously-edited 1959 volume THE SCIENCE FICTION NOVEL (here), but is substantially longer than either of those.

Reginald Bretnor’s 1953 Modern Science Fiction: Its Meaning and Future is one of the earliest critical volumes about SF. If follows Lloyd Arthur Eshbach’s 1947 OF WORLDS BEYOND (summarized here) and precedes the anonymously-edited 1959 volume THE SCIENCE FICTION NOVEL (here), but is substantially longer than either of those.

The book consists of 11 essays written (with one partial-exception) especially for it, and the contributors range from Heinlein, Asimov, and Clarke, to relative unknowns like Don Fabun and Rosalie Moore.

The first section of three essays is about “Science Fiction Today”.

John W. Campbell, Jr.’s “The Place of Science Fiction” is a quick survey of human history that identifies SF as a response to the current state, since 1910 or so, of permanent ongoing change. He notes that interest in SF increased significantly following the atomic bomb in 1945 (i.e., as one of early science fiction’s wild-eyed ‘predictions’ that actually came true). SF, Campbell says, is a kind of practice zone, a place to try out new ideas before implementing them in a world where they might be too dangerous. And he makes a case that, while the circulation of SF magazines is tiny as a part of the overall population, his own Astounding is reaching “about one third of the men in the most creative age levels who are interested in technical developments.”

Also worth noting is that Bretnor in his introduction, Campbell in this piece, and Boucher in the following, all claim that SF “as a self-aware system of literature” in Campbell’s words, is just a quarter century old.

“The Publishing of Science Fiction” is by Anthony Boucher, co-founder and at the time still co-editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, as well as being a mystery reviewer and author of seven novels. (And like Bretnor, and Fabun, and Moore, lived at the time in Berkeley or nearby the Bay Area, according to Bretnor’s bio notes.) Boucher sketches out how the distinction between ‘popular’ and ‘serious’ fiction was a recent one, using mystery novels as a first example. Such genre books had a guaranteed minimum audience, so publishers learned they couldn’t lose money on such books; yet neither could they make big money. (Aside: Boucher refers a couple times to ‘rental’ libraries that many readers would use rather than buy books outright, which in that day cost typically $2.50 for a hardcover. This is a concept outside of my personal experience.)

Boucher goes on: The history of SF began with Hugo Gernsback and his magazines. Amazing, 1926; Astounding, 1930; Campbell taking over Astounding, 1937, with the field expanding to some 30 magazine titles (!) at the time of writing. Book publishing became feasible as interest in SF was triggered by the atomic bomb. The first anthologies were the two big ones in 1946 [Raymond J. Healy & J. Francis McComas, eds. • Adventures in Time and Space and Groff Conklin’s The Best of Science Fictin]. SF books are different than mysteries in that far more of them are anthologies, and SF readers keep buying hardcovers for years, even after paperback editions are available. (Whereas, apparently, mysteries were more like commodities, one book ceasing to sell as soon as the next came along.) And are willing to spend money to buy books from specialty houses like Arkham House, et al.

Still in recent years, most SF books are reprinted from magazine serials: in 1949, 15 sf novels published from magazines, 5 without previous publication; in 1950, 29 and 13; in ’51, 17 and 14; etc.

Writerly pay? In this era, typical rates were $100 for a short story, $1200 for a novel, for an annual salary [for a full-time writer] of perhaps $3600. (Note reference to the “newly organized Science Fiction Writers of America” – p40, in 1953! Obviously this never came about; the SFWA we know was formed by Damon Knight in 1964 or so…)

*

“Science Fiction in Motion Pictures, Radio, and Television” is by Don Fabun, at the time a reviewer for the San Francisco Chronicle. He explains the disappointing examples of SF in the mass media as being an effect of how the mass media needs to reduce complex prose to simple pictures. SF is built on the myth that “the mind of man is capable of solving all problems directed to it by the exercise of rational thinking and through the logical disciplines of orthodox science.” P47.0. But mass audiences need emotional appeal, or character symbols — the heroine, the villain, and so on. So when SF was adapted for mass entertainment the obvious model was the western; thus, ‘space opera’ like current TV shows of the time. These shows aren’t just for juveniles — p49m “Any theatre manager who stands in the lobby of his theater and listens to the remarks of this departing patrons will agree that, no matter how juvenile his fare for the evening, many of the people going out apparently have failed to understand it.”

Fabun goes on to examine SF films. The first successful SF film was Rocket Ship X-M in 1951. Soon after that, George Pal’s Destination Moon, successful, very accurate, but rather documentary-like. The Thing was next, also very successful – but a prime example of good prose story made “a complete and inexcusable mess” p53m. Also in 1951, The Day the Earth Stood Still, which writer here calls “a wan mish-mash of several science-fiction themes, carried out in a weary manner which made one think that the producers must have had a captive audience in mind.”

He then moves on to TV, with very detailed descriptions of the popular shows, and their radio antecedents — Buck Rogers in 1932, superseded by Superman, then Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds radio broadcast.

On TV, Captain Video came on in June 1949, Tom Corbett: Space Cadet in October 1950; then Space Patrol. Writer describes their doubletalk gadgets and weapons (cosmic ray vibrator; atomic rifle; thermoid ejector; nucleamatic pistol, etc., p63b) and how they all had prohibitions against bloodshed, violence, and death. These were serials, shown up to five days a week in 15 minute or half hour segments, both live and filmed.

Tales of Tomorrow was an anthology show adapting short stories, e.g. Heinlein’s “The Green Hills of Earth.” The problem was with needing writers – the assumption here is that writers for TV had to establish a track record in print first, then be able to write dramatically; still, most TV productions are written by TV writers, who often adapt stories from print. Example from a 1952 magazine article, of outlining a story, getting technical advice from Willy Ley, turning out a script in a week, and to the director just one week before telecast.

(I won’t bother to comment on how these assumptions have changed radically, again and again, over the decades since.)

In time, Fabun predicts, most SF might be written primarily for TV or motion picture screens (rather than adapted from published stories).

*

The next section, “SF as Literature“, begins with Fletcher Pratt’s “A Critique of Science Fiction.” His issues are familiar even today as criticisms of bad science fiction; many of these still apply, only a few have been overcome by SF’s merging with popular culture. I’ll bullet-point them.

- SF has too many unscientific elements, e.g. the fiction of A.E. van Vogt. Writers owe us at least plausible explanations for how something should work; else we have pseudo-science, the “label we all hate so much” p75.7. (But see my point on this issue, about a similar comment by Heinlein, here)

- It’s bad when authors produce new gadgets at the end of a story to solve all the problems. [Some episodes of various Trek incarnations, anyone?]

- Characters who all sound the same; no details of everyday life. George O. smith, EE Smith.

- Stories with a brilliant concept but no story– “The Absolute at Large”; “E for Effort”; “The Xi Effect”.

- Gigantism, in which the stakes grow to whole galaxies at war, and so on; Foundation; de Camp’s Johnny Black, often in response to editorial urging of more and more sequels. [ Of course this is a common feature of modern SF superhero and space opera series. ]

- Writers who imagine English spoken by aliens, or the same English in the far future. [ too many examples…]

- Using terms of disintegrator and space-warp, perhaps only understood by cultists. [ not any more! ]

- Mystification via mumbo-jumbo. Van Vogt.

- The cult of the superman story. Stories in which we wonder why characters who have some unusual ability that makes us wonder why they don’t use it to take over. Sixth Column.

- The overuse of surprise ending, especially currently in Galaxy magazine.

- And how SF dates, both in the language of the writing of the time, and in obsolete predictions. When the Sleeper Wakes.

*

I’ll not summarize all of the following essays in quite such detail.

Rosalie Moore’s “Science Fiction and the Main Stream” says a lot of obvious things about how we read a fantastic story differently from a realistic or mainstream story, a theme developed greatly in decades since, notably by Samuel R. Delany. She does make some familiar points about the difference between a mainstream story and an SF one. 115.4: How “all too often the effect of the mainstream story—over and over—was one of dejections and defeat.” Mainstream stories conclude, “Isn’t it terribly sad?” while sf asks, “Precisely what are we going to do next?” And how “the typical New Yorker” story, p116b, is about frustration and taking no action. As if the idea of plot is vulgar. 117.4

L. Sprague de Camp’s “Imaginative Fiction and Creative Imagination” is about how de Camp writes stories. Creative imagination is about free association. A handicap for any writer is simply not knowing enough. A writer’s sources are his experiences, personal or vicarious. Killdozer. These can include legends and myths, the author’s contemporaries, paying attention to the progress of science. A writer is trying to do three things: entertain the reader; express himself and his feelings; and convey some idea or opinion. He goes on to explore why SF depends on the glamor of the exotic, to explain why stories about the future should exploit “such archaisms as pre-gunpowder weapons, hereditary monarchy, and all-powerful hierarchical religious cults”. Not all progress is uniform. And most cultures have a “myth of a heroic age, when mankind was young and all men were virile, all women beautiful, and all problems simple.” 135.4, followed by “the modern Western belief that ancient times were mostly hard, cruel, dreary, and unsanitary, while probably closer to the facts that the heroic-age concept, is a relatively new one.”

*

The final section, “Science Fiction, Science, and Modern Man“, begins with the longest essay in the book, by Isaac Asimov, about “Social Science Fiction.” This strikes me as an essential, classic essay, but perhaps I think that only because I read this essay in Damon Knight’s volume TURNING POINTS back in 1977, and it struck me at the time, especially because I didn’t think I agreed with it. In this essay Asimov makes a distinction between proper science fiction and mere ‘social’ science fiction — like Gulliver’s Travels, or More’s Utopia.

I think at the time I thought Asimov was being persnickety, trying to distance himself, and his own brand of proper science fiction, from the claimed antecedents who didn’t really do it the way he thought it should be done.

(As an aside, I had a well-read friend once, not an SF fan, who was flabbergasted that anyone would try to claim NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR as science fiction. I think his literary intuitions aligned with what Asimov was trying to get to in this essay.)

Asimov claims it’s a question of intent. He describes literature’s response to increased change over recent centuries in phases: social fiction, then gothic horror fiction, then science fiction. And he declares his new definition of science fiction, p167.4: “Science fiction is that branch of literature which deals with a fictitious society, differing from our own chiefly in the nature or extent of its technological development.”

Asimov goes on to describe four eras in the history of science fiction: 1815-1926; 1926-1938; 1948-1945; 1945-present. The earliest was ‘primitive’; the second defined by Gernsback founding Amazing Stories; the third by Campbell taking over Astounding; the final by the atomic bomb.

He then goes on to distinguish between ‘chess game stories’ and ‘chess puzzle stories.’ The rules by which pieces move are the impulses of humanity [human nature] – p178m. The chess game story has a fixed starting position, our own socio-economic society: the city, an agricultural economy, etc. p179.3.

The purest chess-game story takes advantage of the idea that “history repeats itself.” Asimov has used this idea repeatedly – in his Foundation stories, in other novels, 180t. [Asimov knows his history! More than most casual readers, I’d guess.]

Noting that author and critic Damon Knight has taken issue with this idea [in a review reprinted in Knight’s IN SEARCH OF WONDER], Asimov counters with a detailed outline of an historical episode, with blanks for key names, p181-183, and then provides a table of three columns, each a set of names to fill in the blanks: 17th century England; 18th century France; 20th century Russia. There are a few mismatches, but the number of matches is impressive.

Then he provides some examples of ‘chess puzzle’ stories by Leiber, Wyman Guin, Tenn, Russell, de Camp.

Finally he considers the effect of SF on society, and dismisses the idea that SF is only escape literature. The future has to be thought about, and SF can accustom the reader to the idea of change. He cites FDR’s willingness to experiment; that’s what SF does. And the effect of SF is to expand the scope, to break down hostility between tribes and states, to consider anything less that “Earthman” doesn’t make sense.

Summary 195-6:

“1. For the first time in history mankind is faced with a rapidly changing society, due to the advent of modern technology.

2. Science fiction is a form of literature that has grown out of this fact.

3. The contribution science fiction can make to society is that of accustoming its readers to the thought of the inevitability of continuing change and the necessity of directing and shaping that change rather than opposing it blindly or blindly permitting it to overwhelm us.”

….So after all these years I’m more sympathetic to his distinction between “social science fiction” and other forms of SF than I was when I read this essay 40 years ago. Though not quite on basis Asimov makes it, but from another perspective, analogous to my distinction between SF and fantasy, where the former is about recognition of an objectively knowable universe, distinct from human values, and the latter is a literature in which human values, and wishes and dreams, are projected into various imaginary settings. What Asimov calls social SF is, in a sense, an extrapolation of human nature, rather than a consideration of how human nature reacts to discoveries of science or changes in technology. So that might indeed dismiss Plato et al from SF; but not Orwell, and surely not Huxley, whose imagined dystopias do indeed depict social changes in reaction to technological changes.

*

In contrast, Arthur C. Clarke’s “Science Fiction: Preparation for the Age of Space” is a rather dry survey of the various ways writers over the centuries have imagined voyages into space. Clarke doesn’t mention the book, but he might well have read J.O. Bailey’s PILGRIMS THROUGH SPACE AND TIME, a 1947 survey of the many precursors of utopian thinking before modern SF, all the names that most of the writers here dismiss as not belonging to the modern genre. (I have a copy of this book too, but am not motivated to read it.) Thus, Clarke describes voyages into space via the supernatural (Kepler, Stapledon, Lewis); by natural agencies (Lucian of Samons, Bishop Godwin; de Berjerac); via ‘subtle engines’ such as wings, firecrackers, or magnets; space guns in McDermont, of course Verne, and the 1936 Wells film; antigravity; rockets; miscellaneous; and space stations.

*

Philip Wylie’s “Science Fiction and Sanity in an Age of Crisis” is fascinating in its revelations of what worried people in the 1950s. Democracy requires an educated citizenry, but we live in an increasingly complex society in which it’s impossible to keep up, in which everyday people are necessarily specialists, and Congress is ignorant about the atom. In fact Congress took the action to assign such knowledge (of the atomic bomb) to the military, making it ‘secret’ — a subversion of democracy, Wylie claims. That’s what he’s worried about — an unprecedented development, he seems to think, about an issue (secrecy) that we take for granted today.

So is SF educational, he wonders? Does it help people to reason, or merely muddle their thinking? Does SF have any obligation to the standards of science?

His answer: it can help, but it seldom does. SF isn’t mythology; it’s religious in form, but must be honest toward outer objects. On page 232 he says this: “This is, essentially, a mere transposition of the subjective teaching of Jesus to the outer world. Many authors have said, rightly, in the opinion of this one, that true science was impossible before the teachings and ideals of Jesus had been disseminated.” I have no idea what he means; it doesn’t correspond to anything I understand from reading the NT or about the history of science.

He goes on to worry primarily that SF doesn’t take into account what is known about “man’s nature” — that is psychology. “Without a science of such matters, what they write is irresponsible, in the sense that it pretends to be ‘modern’ whereas it is contemporary in detail only—and inevitably, in meaning, archaic.” The result is that SF has made audiences credulous about matters like flying saucers. The amorality of SF/F is a symptom of a general mental disorder. He mentions Freud, Adler, and Jung, about the importance of myth, and implies this understanding is what is lacking in SF.

This piece suffers because Wylie alludes to good and bad examples of SF, without naming any of them. Presumably he assumed his readers know what’s talking about; but 60 years on we can only guess.

What I find extraordinary about the essay, though, is that he was on to something — psychology was indeed primitive 60 years ago, but it has advanced greatly since — cf. Kahneman, Haidt, Pinker, McRaney — and in fact understanding of this psychology can deeply inform our understanding of human interactions, of politics, of science fiction and fantasy. If mainstream fiction has done better at portraying human nature, it’s done so intuitively, unconsciously. Whereas scientific understanding of psychological issues — mental biases and the persistence of logical fallacies in everyday life — has in fact begun to filter down into the fiction of SF authors. The first example that comes to mind is KSR’s AURORA…

*

The next essay is “Science Fiction, Morals, and Religion,” by Gerald Heard (http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/heard_gerald), an author and journalist mostly forgotten by now, I think. For me this was the most intriguing essay in the book, for its topic; what were the issues about morals and religion in the 1950s that science fiction had anything to do with? Heard quickly identifies several issues: artificial insemination; the understanding that hormones affect human personality; the general issue of what is ‘natural’ and whether science can enforce the “simplicities which uninformed moralists thought was all that was natural.” More broadly, how will atom bombs affect how power is fought? And what will future societies be like, as individuals become increasingly specialized?

SF can address not just the “pursuit of truth” but the idea of “future alternate universes” and identify what the potentials for humanity might be. SF can build up a ‘tolerance’ to new ideas (unlike, he claims, science, with its failure to take reports of ESP or flying saucers seriously -!! p260).

Heard’s style is roundabout and pompous, as if he assumes the reader knows and agrees with his conclusions so that he need barely mention them, let alone spell them out. He finally gets around to discussing religion in the middle of a long paragraph on p261 and, typically, claims no conflict between science and religion: science is empiric research, religion is the frame of meaning, and how those meanings are applied is morality. This makes religion alive in a way it was not when all it did was defend the past and its “outgrown cosmogonies, inaccurate history and inapposite codes.” And he goes on about Julian Huxley and how the pessimism of evolution and materialism has been overcome. (It has?) And so a task of SF is to “construct an ethic deduced from a modern cosmology and producing rules of demonstrable psychiatric, hygienic and social value.” OK. But he loses me when he claims that meaning is not just anthropomorphic or mechanomorphic. …rather “an extension of conscious thought which indicates and will tend to explicate a vast directive, a concept that is more inspiring to the modern mind than any forecast of a concrete goal.” (p264.)

*

Finally, editor Bretnor’s “The Future of Science Fiction” spends time defining SF, and then defending it from ‘mainstream’ detractors.

Like a couple others he’s concerned with the problem of modern-day specialization, and claims the misunderstanding of science, and the scientific method, is a driver for the emergence of SF. p272: “Today, science fiction appears as a genre because the main currents of our literature still adhere to sets of principles which are pre-scientific – principles whose validity can only be maintained by rigidly excluding the knowledge which would prove them false.”

His definition of SF again stresses awareness of the scientific method. He identifies three categories, in descending order:

1, works which reveal the author’s awareness of the scientific method not just in circumstance and plot but in the thoughts of its characters;

2, works with such an awareness, but only in circumstance and plot;

3, works that reveal the author is aware only of the products of the scientific method.

While ‘serious’ fiction emphasizes feeling rather than thought. And with this he challenges critics in the popular press who disparage SF on one ground or another. One of his examples is the paragraph from Saturday Review that Heinlein further attacked in his essay in THE SCIENCE FICTION NOVEL. Another is a mischaracterization by Look magazine of Donald Menzel dismissing a particular UFO incident — Look implied the entire field of UFO studies was thereby discredited. Bretnor then makes this extraordinary statement:

This statement is in the same general category as—to use the most familiar of absurd examples—those which flatly deny the existence of a God or gods, the possibility of survival after death, the actuality of ESP phenomena, the prevalence of witches, or life on other worlds, or poltergeists, or the meteorological effectiveness of the Hopi snake dance.

Is he serious? Three sentences later: “Nevertheless, much evidence has been accumulated—evidence of varying reliability, true—which indicates either that they exist or that some corresponding areas do.” Is that so.

Bretnor does distinguish between the “verified” “new maps” of Heinlein and Clarke, and the topics mentioned above for which no “new maps” have been drawn, but that this does not mean the latter are automatically fantasy.

(Is he coining the term “new maps” or quoting someone else? Can’t tell. Kingsley Amis uses the term a few years later in his book NEW MAPS OF HELL.)

And then Bretnor sketches the future of SF: the adoption of the attitudes of SF by non-SF; increased academic interest; mediocre SF by non-SF writers; and the growth of the field, including one ‘slick’ magazine within two years. (On this last point, I don’t think it ever happened, with the exception of Analog‘s switch to slick format in the early ’60s, only for a couple years.)

*

To summarize key, repeated points:

-

- SF as a distinct genre was, in 1953, only a quarter century old

- Much of it is poorly written and conceptually shallow

- Media (movie and TV) SF is even worse

- SF became ‘respectable’ following the atomic bomb

- Opinions about UFOs, parapsychology, and the like, varied widely, but the subjects were taken quite seriously by some

- Proper science fiction is about the impact of technology on society and especially relies on conscious application of the scientific method, and is a benefit to society by helping readers cope with continuing change.

In April 2017 I sat down, having planned for many years to do so, to systematically rewatch Star Trek, the original series, that ran from 1966 to 1969. I was 11 years old when the series debuted, and I saw most of the episodes when they were first broadcast (albeit in black and white), and the show had a great and lasting influence on me. When the show went into syndication (that is, reruns shown by local TV stations typically five nights a week) in 1969, I became obsessed with the show, catching up on episodes I’d missed, and compiling notes on each episode, e.g. the stardate(s), names of any guest crew members, names of planets, and so on, as my own personal concordance. I read James Blish’s adaptations and Stephen Whitfield’s THE MAKING OF STAR TREK over and over.

In April 2017 I sat down, having planned for many years to do so, to systematically rewatch Star Trek, the original series, that ran from 1966 to 1969. I was 11 years old when the series debuted, and I saw most of the episodes when they were first broadcast (albeit in black and white), and the show had a great and lasting influence on me. When the show went into syndication (that is, reruns shown by local TV stations typically five nights a week) in 1969, I became obsessed with the show, catching up on episodes I’d missed, and compiling notes on each episode, e.g. the stardate(s), names of any guest crew members, names of planets, and so on, as my own personal concordance. I read James Blish’s adaptations and Stephen Whitfield’s THE MAKING OF STAR TREK over and over.