FAREWELL SUMMER (2006) is a belated sequel to Ray Bradbury’s famous novel DANDELION WINE (1957), the book set in a fictionalized version of the town Bradbury grew up in, in Illinois, named in the books Green Town. (My post about DW is here.) The ‘novel’ DW was actually a composite novel that included numerous short stories RB wrote in the early 1950s and then assembled within a frame story about the 12-year-old Douglas Spaulding experiencing the summer of 1928, with his realizations of his being alive, and that he would someday die.

In the ‘core bibliography’ for Ray Bradbury that I posted here, you can see that FAREWELL SUMMER was one of the last books published in Bradbury’s life. It was one of a number of final books that RB issued beginning in the early 1990s, up until his death in 2012, books that mostly contained work he had written decades before and never sold.

In the ‘core bibliography’ for Ray Bradbury that I posted here, you can see that FAREWELL SUMMER was one of the last books published in Bradbury’s life. It was one of a number of final books that RB issued beginning in the early 1990s, up until his death in 2012, books that mostly contained work he had written decades before and never sold.

(That these late books were published was, I think, perhaps, because at this same time in the early ‘90s, he made a deal with Avon Books to reissue five of his core books – TMC, TIM, TOC, DW, SWTWC – in new hardcover editions, and perhaps this deal involved publishing a couple new collections, namely QE and DB, as well. Later books were then published by William Morrow… I suspect a key editor was involved.)

Thus, the last half dozen of Bradbury’s short story collections, beginning with QUICKER THAN THE EYE in 1996, were mixtures of a few recently written and published stories (in magazines like Playboy and F&SF), with many more previously unpublished stories, which commentators at the time realized were ‘trunk’ stories, i.e. stories written years or decades earlier and tossed into a real or figurative truck after they’d made the rounds of potential buyers, but did not sell. Bradbury perhaps had hundreds of these; somewhere I read that he wrote at least one short story a week, and if he did that from the 1940s to the 1990s – or, since his pace curtailed in the ‘60s, then even from the 1940s to the 1960s — he must have produced 600 or 700 stories over that time; and the result we have in all his published collections, even including these later ones, is at best three hundred stories. So there are a lot still unaccounted for, in some trunk.

Not all writers work that way, but RB was an inspirational rather than a methodical writer, and in some of these later collections he appends afterwords in which he describes the circumstances that inspired this or that story, and how he would go home and bang out said story in a couple hours. It’s no wonder that all of them didn’t sell.

In the case of the present book, the backstory is even more interesting. Published in 2006, it was billed as the “eagerly anticipated sequel” to DANDELION WINE, though frankly I doubt anyone had been eagerly anticipating such a sequel, or knew that such a sequel might exist. Once it was published, though, it became third of a trio of Green Town books, along with DANDELION WINE and SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES, now all tagged as a series, at least by Amazon.

RB provides an afterword to this book, also, in which he explains where this book came from. In the mid 1950s (several years after the successes of THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES and THE ILLUSTRATED MAN) he submitted a manuscript to his publisher, Doubleday, for the book that became DW. But that original manuscript was too long and his editor suggested cutting it. RB quotes his reply (p210 in FS): “ ‘Why don’t we published the first 90,000 words as a novel and keep the second part for some future year when you feel it is ready to be published.’ At the time, I called the full, primitive version The Blue Remembered Hills. The original title for what would become Dandelion Wine was Summer, Morning, Summer Night. Even all those years ago, I had a title ready for this unborn book: Farewell Summer.”

With DANDELION WINE such an entrenched classic, it’s difficult to imagine how the content of FAREWELL SUMMER could have been incorporated into it. That would have been a completely different book. As it came to be, DW has a perfect story arc, across one summer in the life of a 12-year-old. Yet even as a leftover, on its own, FS is a quite different, a rather oddly amazing and moving, book.

To begin with, it’s not a fix-up in the same way DW was. I’ve seen no evidence that parts of it were previously published in separate pieces, with just two possible exceptions.

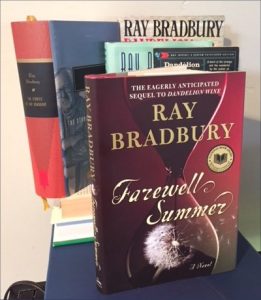

First is a 6-page story called “Farewell Summer” that was included in the 1980 compilation of 100 Bradbury stories published by Knopf, with no previous publication credit. (The 1980 book was reissued by Everyman’s Library in 2010, the edition I have, in the photo above.) It describes the boy Douglas taking a nap and dreaming of a band playing outside, where all the players are his own family, and this band leads him down to the lake shore, and then onto a boat, which is pushed out onto the lake, leaving him alone… He wakes up, tells his Grandpa about it, and realizes the dream was a metaphor for death. This story is included in an early chapter of FS.

Second is a startling passage late in this book, FS, that describes Douglas’ awakening into puberty, very delicately described. Here it serves in the conclusion of the book, in the resolution of its war between the young and old, as part of a sort of passing of the torches, in the cycle of life. The precedent here is “Junior,” a story first published in THE TOYNBEE CONVECTOR (1988), about an 82-year-old man named Albert who discovers one morning his “Albert Jr.” has emerged, and isn’t going away. He calls three lady friends, with whom he’s had friendly non-committal relationships over the years, to come and admire it, realizing it will never happen again in ‘this life’. Yes, Ray Bradbury is talking about sex, he’s talking about male erections, and it’s startling, I admit, to discover this story, and the similar passages in FS, after a lifetime of thinking that Bradbury is all about the preeminence of innocent childhood and the dangers of adulthood. (As it turns out, there are a handful of other stories in RB’s oeuvre with similar concerns, which I’ll get to in later posts.)

Aside from these echoes of late-published fragments, the key issue about FAREWELL SUMMER is this: it’s a through-story, one that doesn’t involve asides about other characters in the way DW does, though it does alternate between two sets of characters. It’s set a year after the events of DW. It concerns a war between youngers and elders, progress vs. stability, and ends with Douglas Spaulding’s discovery of physical change. It’s a completely different theme and story arc than what we’ve lived with in DANDELION WINE for these 60 years; yet on its own terms, despite some awkwardness of plot, it’s quite affecting and moving. A secondary issue is, there’s even less fantasy content than in DW; the suggestion of ghosts fleeing a haunted house is about it.

The book is also fairly short, 205 pages of largish type, in 37 chapters with blank pages between many of them.

Here’s the rough summary of FAREWELL SUMMER. It begins on October 1st, the end of a lingering summer, when Douglas is almost 14 — so this is just one year after the summer described in DW. (It’s mentioned, p30.2, that Douglas is a C-minus student.)

Douglas and his friends run through the ravine, and pee on the creek bank, tracing out their names – another adult bit such as you never saw in DW – and vow war against the houses along the edge of the ravine occupied by old men, Braling and Quartermain. One of these old men actually says to them, “Get off the lawn!” The boys’ pranks with cap-pistols scares Braling to death. Quartermain and another old guy, Bleak, occupy the school board, and plan to change the rules to keep the kids off the streets.

The boys stage various attacks against the old men. They steal the old men’s chess pieces, as they play chess in the town square; they sabotage the town clock, thinking it somehow alive and controlling the march of time—here’s a quote, from p100:

There, in the shellac-smelling, paper-rustling rooms of Town Hall, the Board of Education slyly unmade destinies, pared calendars, devoured Saturdays in torrents of homework, instigated reprimands, tortures, and criminalities. Their dead hands pulled streets straighter, loosed rivers of asphalt over soft dirt to make roads harder, more confining, so that open country and freedom were pushed further and further away, so that one day, years from now, green hills would be a distant echo, so far off that it would take a lifetime of travel to reach the edge of the city and peer out at one lone small forest of dying trees.

Douglas’ grandpa intervenes and makes Douglas repent. Meanwhile, the old men have second thoughts. Quartermain realizes that Douglas is the grandson he should have had, and wonders what he can do for the boy to redeem his own life. He begins by staging a birthday party, in that famous Green Town ravine, which Douglas and his friends attend. And Douglas is struck by the sight of a girl, Lisabell:

He was suddenly conscious of the grass under his shoes. His throat was dry. His tongue filled his mouth.

Again, something we never saw in DW, or any other of RB’s famous books, where the worlds of childhood and adulthood were

Final scenes involve a haunted house, Lisabell showing up to kiss Douglas, and a bizarre “mystery tent” scene in which the old men – who apparently have medical backgrounds – put on display a series of jars full of odd shapes, like oysters, or seaweed, or small animals, but which Douglas and his friends realize are all babies, in various stages of life. Douglas is overwhelmed, by this blunt demonstration of the mysteries of human life, and his recognition that he is a part of it:

He took a deep breath of the hot summer-like air, and squeezed his eyes shut. He could still see the platforms and the tables and the glass jars filled with thick fluid, and in the fluid, suspended, strange bits of tissue, alien forms from far unknown territories. What could be a swamp water creature with half an eye and half a limb, he knew, was not. What could be a fragment of ghost, of a spiritual upchuck come out of a fogbound book in a night library, was not. What could be the stillborn discharge of a favorite dog was not. In his mind’s eye the things in the jars seemed to melt, from fluid to fluid, light to light. If you flicked your eyes from jar to jar, you could almost snap them to life, as if you were running bits of film over your eyeballs so that the tiny things became large and then larger, shaping themselves into figures, hands, palms, wrists, elbows, until finally, asleep, the last shape opened wide its dull, blue, lashless eyes and fixed you with its gaze that cried, Look! See! I am trapped here forever! What am I? What is the questions, what, what? Could it be, you there, below, outside looking in, could it be that I am … you?

(This seems to be another episode that might well have been published separately, though, again, I’ve seen no evidence of such.)

And so the war between olders and youngers simply deflates. Douglas is suddenly attuned to another whole level of existence. He notices girls. He visits the old man, Quartermain, asking what life is about. Quartermain prepares to answer, and the scene shifts to the situation similar to that in “Junior” – the old man Quartermain waking up in the night, aroused for the first time in years, feeling a second heartbeat. Saying farewell, a voice in reply saying goodbye.

And then in a matching passage, Douglas awakes at 3am, feeling something down where his legs join, and he speaks to it. “Where did you come from?” The voice replies: “A billion years past. A billion years yet to come”. Inside those glass jars, in a way. Every boy names us, the voice says; every man says that name ten thousand times in his life. “You have two hearts now. Feel the pulse. One in your chest. And one below. Yes?” p203. Are we friends? “The best you ever had. For life.”

And then Summer’s finally over. Douglas goes to bed, little brother Tom worries about dying, Douglas comforts him, and Grandma sits downstairs and “named the season just now over and done and past.”