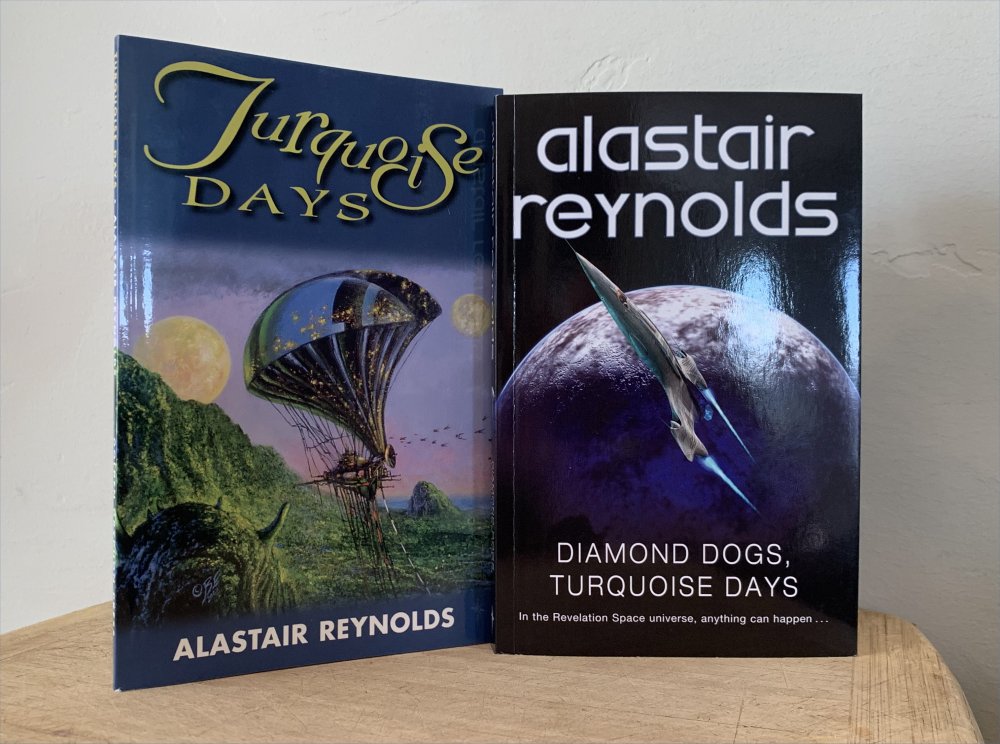

This week’s Sunday novella is “Turquoise Days” by Alastair Reynolds. It was first published in a thin chapbook from Golden Gryphon Press (shown left in the photo above) in 2002, then in a two-novella collection, Diamond Dogs, Turquoise Days, from Gollancz a few months later (and which is still in print). Then in the Dozois anthologies, first the 20th Annual and then this Best of Best Volume 2 volume under review. And that’s it; it did not, for instance, appear in the author’s Best of collection, Beyond the Aquila Rift in 2016, though “Diamond Dogs,” from 2001, did.

This is the last story in the Gardner Dozois anthology, The Best of the Best Volume 2, that I’ve been reading along with a Facebook group called Best Science Fiction and Fantasy Short Fiction. The book includes 13 novellas published from 1985 through 2002; the first was Robert Silverberg’s “Sailing to Byzantium”, reviewed July 29th. (The group reviews one story every Sunday.) As I mentioned when we began, the period includes the era in which I reviewed short fiction for Locus Magazine once a month, and so had already read most of the stories; the exception was this one, published after I retired from the Locus column in 2002 (and abandoned reading short fiction almost cold turkey for several years). So I have no reviews, old notes, or memories to consult; I read this story freshly this past week.

Like the Ian McDonald story reviewed two weeks ago, “Turquoise Days” is set in a universe covered in several or many of the author’s other works. With McDonald, it was a couple novels and couple other stories; with Reynolds, it’s half a dozen novels (including his first four) and a dozen or more other stories. (Actually, only two of the novels and half a dozen of the stories precede this one in order of publication.) And I’ve only read a handful of the Reynolds titles. (I’ve like what I’ve read, but have been intimidated by the novels because they’re all so long and there are so many of them. Yet still I’ve accumulated a dozen of them…)

“Turquoise Days” is part of Reynolds’ vast “Revelation Space” universe, set in a far future in which human colonies have become scattered across many star systems over many centuries, but which mostly exist in semi-isolation, because the impossibility of faster-than-light travel makes interstellar travel slow and arduous. Reynolds wrote some short fiction in the 1990s, but made his mark with his lengthy first novel, Revelation Space, and then followed it up with equally lengthy novels at an almost annual pace. He’s a master of far future, hard SF space opera, and by hard SF I mean that a feature of this series in particular is that FTL constraint. No magic warp drives in Reynolds.

The setting here is a colony world that has not been visited by another ship in a century. Turquoise is a water world occupied by corrosive life that forces humans to live in blimps and gondolas and “snowflake cities” (which occasionally get married). As the story opens news comes of another starship, due to arrive in two years. (A familiar set-up; didn’t we just read this recently?)

Naqi Okpik and her older, more adventurous, sister Mina are studying the world’s key life forms, Pattern Jugglers, that form biomasses in the sea and which mimic a kind of intelligence by creating intricate, shifting structures on their surfaces. The Pattern Jugglers interact with intelligent life that enters the water in some undetermined way, and furthermore apparently exist on many other worlds besides Turquoise. (I’m guessing Reynolds told us more about these creatures in earlier stories; similarly concerning some kind of “worm” embedded in the human body that isn’t explained here.)

In the first section, Mina violates protocol. Prompted by an unprecedented flight of related creatures called messenger sprites, she descends into the water, Naqi following along to protect her. The biomass seems to respond positively to them, at first… Then Mina disappears and apparently dies, while Naqi escapes, never telling anyone she went into the water too.

The second section concerns the arrival of the an “Ultra” ship, bringing members of a scientific organization interested in studying the planet’s relatively pristine population of Pattern Jugglers. Action is centered on a gigantic “Moat” under construction, with the idea of isolating one set of Pattern Jugglers from those around the rest of the planet. But the visitors have ulterior motives, and Naqi responds frantically to an apparent attempt to kill the Pattern Jugglers inside the Moat.

The final section concerns Naqi’s pursuit of the apparent saboteur, and back and forth revelations about who the bad guys are, and who the good guys are, and what their motivations are. Part of it involves an earlier visitor, a tyrant on his home world who escaped into the Turquoise sea (this angle about the tyrant who just happened to come to Turquoise centuries ago strikes me as a rather outlandish wild card of the story). And part of it involves Naqi’s realization that, if the Pattern Jugglers truly retain some essence of those it absorbed, then part of her sister Mina may yet live on. This puts her, in turns, in an impossible situation of deciding whether to help or hinder her antagonist.

So — this is a dramatic story that (as do some of the other novellas in the book) introduces a variety of elements, many of them familiar from other far-future or interplanetary stories, then carefully assembles them into a narrative that becomes more than the sum of its parts. Swanwick’s “Griffin’s Egg” and Egan’s “Oceanic” worked somewhat like this. It may or may not be notable that three of the 13 novellas in this Dozois anthology are set at sea: this one, Walter Jon Williams’ “Surfacing,” and again Egan’s “Oceanic.” (And the last three stories in the book are all by Brits, at least loosely. Or: with Egan, the last four stories in the book are all by non-Americans. Most patterns like these are just coincidences.)