Washington Post, Joel Achenbach and Aaron Steckelberg, 15 Jul 2022: Take a cosmic tour inside the images captured by NASA’s Webb telescope

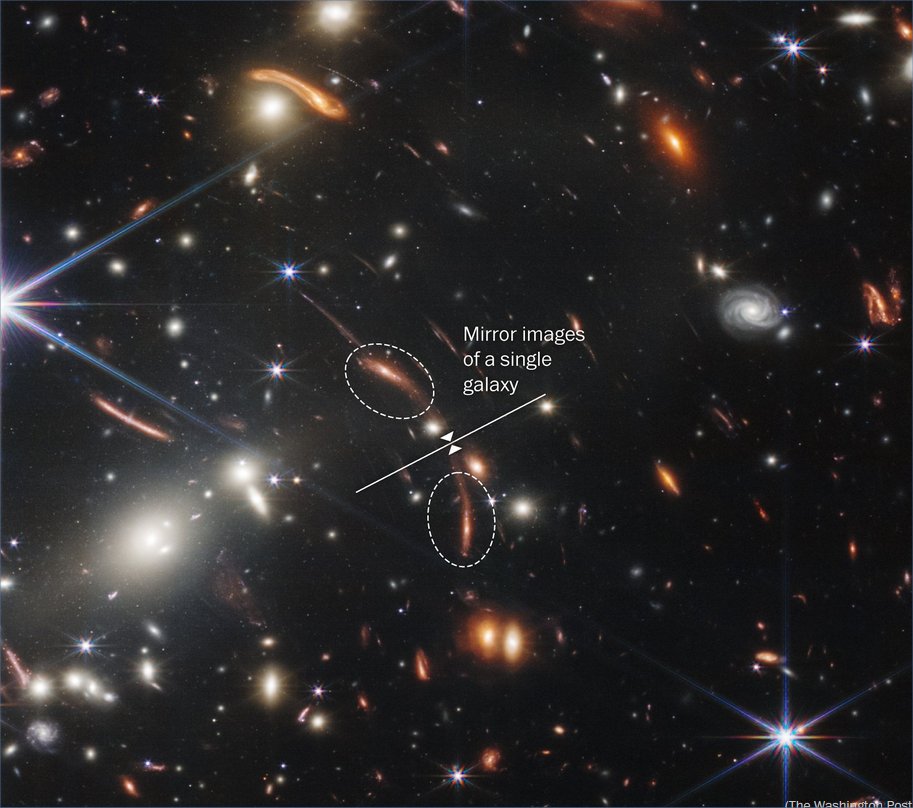

Here’s an excellent interactive guide to the images released this week from the James Webb Space Telescope, highlighting significant aspects of each image. One thing I’d overlooked until now: the deep field photo (shown above in a screen capture from this piece), not only shows distortions due to gravitation lensing of distant galaxies, it even show *mirror images* of a single galaxy as its light has been bent around either side of a closer object.

There’s also a handy chart of the electromagnetic spectrum, from gamma to radio, to show the difference between the “visible” spectrum that human eyes are sensitive to (because, of course, that’s the range where our sun is brightest, and human eyes evolved to take advantage of the brightest light in the neighborhood), and the ranges of the spectrum that the earlier Hubble Space Telescope was sensitive to, and the much larger range the James Webb Space Telescope is sensitive to.

\\

This mismatch of spectrum sensitivity has given rise to some slightly dishonest, or at least disingenuous, headlines.

Slate, Sarah Braner, 15 Jul 2022: The Colors in the James Webb Space Telescope Photos Are Fake

Subtitled: “And that’s OK.”

It’s OK and it’s been routine for decades, as telescopes sensitive to areas of the EM spectrum outside human vision take photographs. How would we see them, unless the IR or UV light were “translated” up or down the spectrum? The headline implies this is a dishonest thing to do; but it’s unavoidable.

A Google search turns up this piece on a NASA sight from 2016. Clearly they were anticipating this.

Blueshift (a NASA astrophysics blog), 13 Sep 2016: The Truth About Hubble, JWST, and False Color

\\

And there are also fair cautionary pieces like this one.

Slate, Jaime Green, 13 Jul 2022: Surely There Must Be Someone Out There In All That Space

Subtitle: “Right…?”

Well, no, not necessarily.

Scientists study for years and years be able to understand the value of a galaxy unto itself. The rest of us can be awed by its scale, and entranced by the beautiful images (which are not raw images, but extracted by scientists from the telescope data, made beautiful with a layer of human processing and colorizing). So when we find ourselves thinking, Why is this important? Why is this beautiful? Why is this making me feel all sorts of big things? we may take a shortcut to This feels meaningful and immense because it shows there’s room for life in the universe.

But sit with another possibility: What if we are alone? What if there’s no other life at all? What is the value and meaning of all these galaxies and almost uncountable stars, still, then?

The question of life in other galaxies will probably never be truly answered, not in our lifetime nor humanity’s. We may find microbes on another planet, or not. We may, with JWST or another powerful telescope, see the traces of life in an exoplanet’s atmosphere, or we may not; this kind of evidence would hardly be conclusive of anyone running around out there. We may someday pin down the odds of life’s arising, its frequency and predilections, and we may be able to apply those principles to galaxies beyond our own. But humans will never travel to the far reaches of the universe on display in JWST’s images, will never know them with our own eyes or our feet on their ground. …

\\

There’s a vast confusion about orders of magnitude here, yet another example of how, in various ways, humans intuitively count “one, two, three,…four… many”. In so many ways, but especially in terms of space and time, humans have no intuitive conception of the vastness of reality. It’s all “I can reach it” then “I can see it” then “If I can’t see it it’s probably not real and the elitist scientist are lying to us.” Or, more mundanely, spaceships zip past Neptune and Andromeda, fly past the moon and hit Mars, and so on. In science fiction TV and movies, this has been endemic. The examples are like, my cruise ship just passed Catalina and Japan; or my plane missed the landing at Heathrow and landed in Antarctica.

A good example more recently is how the TV news broadcasters keep emphasizing, as they did when it was launched, that the James Webb telescope is a *million miles* from Earth, emphasizing that distance as if it were truly extraordinary.

How is it, and is not, extraordinary? Virtually no one has intuitions about relative distances beyond what one can see to the horizon; they have to be learned. I have learned a few of these: so, off the top of my head — but I’m going to check the exact figures:

- The International Space Station orbits at an altitude of ~250 miles. That’s pretty close, and so it goes around the Earth pretty fast, in about 90 minutes.

- The Hubble telescope orbits Earth at about 340 miles up. It’s pointing at deep space, so it doesn’t matter how fast it goes around the Earth, as long as Earth isn’t in the way of where it’s pointing.

- A geosynchronous satellite, orbiting the Earth high enough so that it goes around once per day (and thus seems to be stationary above a particular point on the Earth), is up about 22,000 miles.

- The moon is roughly 250,000 miles away, thus orbiting the earth even more slowly — once every 29 days or so.

- The Earth is 93 million miles from the sun.

- The James Webb telescope, unlike the Hubble, doesn’t orbit Earth; it orbits the sun, at some point ahead of or behind the Earth’s orbit. A million miles from earth — about four times the distance to the moon, but one 93rd the distance to the sun, and much closer to Earth than Mars or Venus.

- (Do the newscasters who say “a million miles from Earth!” have any idea about the relative distances of Earth, Moon, telescope, Venus, Mars, Sun? A rhetorical question.)

And so on. The nearest star is four light years away. The Milky Way galaxy is 100 thousand light years across. The nearest galaxy to the Milky Way, Andromeda, is 2.5 million light years away. The Hubble and Webb telescopes are seeing objects 13+ billion light years away… and therefore, we are seeing them as they were that long ago. It boggles the mind.