This is Silverberg’s most highly-regarded novel, and one of his most unusual. It was published in 1972, near the end of a period during which Silverberg wrote one or two critically acclaimed novels a year, from roughly 1967 to 1976. This one was followed by just two others (THE STOCHASTIC MAN and SHADRACH IN THE FURNACE) before he retired for several years. When he returned to writing he had different ambitions, shifting to a more crowd-pleasing mode with the sf/fantasy of LORD VALENTINE’S CASTLE.

DYING INSIDE is often likened to contemporaneous mainstream novels that focused on character and that didn’t have simple, linear plots. In particular, this one drew comparisons to the work of Philip Roth: urban, Jewish, full of angst.

The 1960s were a transitional period in science fiction, with the “New Wave” writers trying out literary techniques on traditional SF themes, others, like Silverberg, becoming increasingly sophisticated and getting books like this one published that would have been unthinkable in SF a decade earlier.

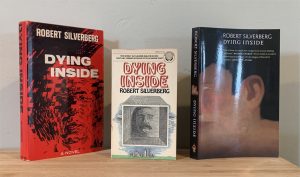

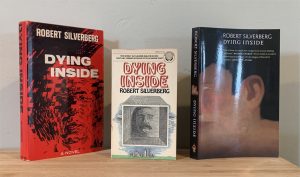

(The photo shows the 1972 Scribner’s first edition, a 1976 Ballantine paperback edition, and the 2009 Orb trade paperback edition, referenced here. In the introduction to the 2009 edition, he lamented that the book had always had dour covers, which discouraged bookstore sales. Apparently this has always been true.)

Overview:

It’s a non-linear novel with very little plot; it’s about a 40-something year old man, David Selig, pretty much a loser, who makes a living ghost-writing college papers for Columbia students. The key fact about Selig is that he’s been able to read minds for all his life, and is now losing this power.

The narrative alternates between present and past, between first person and third (and second in one section). We learn about his sister and the two women he had brief relationships with. And about how he meets another man with his power, and learns that a tiny handful of people like them exist across the country. The plot, such as it is, involves a dissatisfied customer of a term paper who, with his friends, beats Selig up; Selig wakes in the hospital, is discharged and brought before the college dean. He has an intense telepathic insight into this man—and then his power goes out, forever.

The closing sections indicate that people, whether they knew of his power or not, have always felt slightly uncomfortable around him, and now they don’t. Is this the root cause for Selig’s shiftlessness his whole life? You’d think a smart man like Selig (he easily learns how to be a stockbroker at one point), with the added insights provided by reading minds, could go far in life. Yet when he gets that stock-trading job, he gets bored and quits.

Occasional chapters feature the essays Selig writes for those college students. These surely reflect essays Silverberg himself wrote as a student at Columbia, though in the intro to 2008 editions he mentions that he researched and wrote an essay on entropy specifically for this book.

The scenes of most science-fictional interest are those when Selig gains insight into how other minds work, even those of insects. Here’s a passage about a bee. He’s wandering around a farm one summer. (Page 111 of the Orb edition.)

A sense of contact. His questing mind has snared another mind, a buzzing one, small, dim, intense. It is a bee’s mind, in fact: David is not limited only to contact with humans. Of course there are no verbal outputs from the bee, nor any conceptual ones. If the bee thinks at all, David is incapable of detecting those thoughts. But he does get into the bee’s head. He experiences a strong sense of what it is like to be tiny and compact and winged and fuzzy. How dry the universe of a bee is: bloodless, desiccated, arid. He soars. He swoops. He evades a passing bird, as monstrous as winged elephant. He burrows deep into a steamy, pollen-laden blossom. He goes aloft again. He sees the world through the bee’s faceted eyes. Everything breaks into a thousand fragments, as though seen through a cracked glass; the essential color of everything is gray, but odd hues lurk at the corners of things, peripheral blues and scarlets that do not correspond in any way to the colors he knows. The effect, he might have said twenty years later, is an extremely trippy one, But the mind of a bee is a limited one. David bores easily. He abandons the insect abruptly…

And just a few pages later he perceives the mind of a dour farmer who in fact has a rich internal life. And earlier, reflecting the racial tensions of the time, he peers into the mind of a black dude named Yahya Lumumba and is overwhelmed by a blast of hatred for whites and Jews—and him in particular.

Summary outline

Here’s a brief chapter by chapter summary of the whole book.

1, Set in the present, 1st person. David Selig, thinking of his telepathic inner self as a separate person, heads to Columbia to get work from students there ghost-writing term papers. He was born in 1935 and he’s 41 years old, so the book is set in the slight future as Silverberg writes. Selig watches the Puerto Rican women in his building. Once on campus he makes a contact and a job: $3.50 a typed page, guarantee B+ or higher.

2, Set in the past, 3rd person; at 7 years old he’s taken to see Dr. Hittner to test his psychic abilities. Why doesn’t he have any friends? David is smart enough to tell the doctor what he wants to hear.

3, Present, 1st. He can’t transmit. He’s learned that the deep inner thoughts of all people are the same universal language.

4, A paper on the novels of Kafka.

5, Mixed POV: about Huxley and his notion of a cerebral reducing valve that drugs could lift. Or perhaps flagellation.

6, Why not let it fade? Because it’s what make him special, different.

7, Present 1st. His sister Judith calls, inviting him over for dinner. He’s borrowed money from her before but has resisted lately.

8, About Toni, one of his relationships. He was doing research for an author, and she was his assistant. They lived together a few weeks. He only peeped her 3 times. She moves in with him.

9, Dr. Hittner convinced his parents a sibling would do David good. They tried, had a miscarriage, finally adopted a girl—Judith. David hated her. He tried to wish her dead, but it didn’t work.

10, He recalls his one acid trip, in 1968. He recalls the events of that year. Toni brings home two tabs. Do they do it at the same time? He’s cautious, convinces her to go first, he’ll do it tomorrow. She goes first… and he can’t help but feel it, and can’t escape it. Desperately he tries to explain that he’s reading her mind, but maybe she misunderstands, that he’s making some excuse. He goes to stay with friends, and when he returns, she’s moved out.

11, Campus again, gets orders for five more papers, one from a black dude, Yahya Lumumba. Thinking to peak into his mind to get an idea of the language he would use, DS is overwhelmed by a blast of hatred to whites and Jews and him in particular. He’s thrown out of the contact.

12, The power brought ecstasy. The best years were ages 14-25. He recalls summer 1950, in the country; eavesdropping on a girl Barbara having sex with a neighbor; viewing the world as a bee, then the farmer, a dour man who has a rich internal life.

13, DS visits sister Judith for dinner; she has a 4-year-old, Paul, who seems to hate him. Judith is one of only three he’s ever told. She’s seeing a guy, Karl Silvestri, a PhD.

14, He starts the paper for the black guy but can’t find the voice; it’s terrible.

15, He recalls 1961, visiting his parents when Judith was 16, and perceives she had sex for the first time the night before, and can’t help blurt it out. She’s furious, and never wants to see him again.

16, He visits Nyqvist on a night the city is snowed in. Nyqvist can read minds too. They discovered each other in 1958, living in the same building. Nyqvist perceives that DS feels sorry for himself; why? They become friends. Now, snowed in, Nyqvist locates two single ladies and they get together for sex.

17, He recalls how it started to fade. He free associates. He writes, or imagines writing, a letter to Kitty. Can they get back in touch? She was seeing Nyqvist too. He imagines a short sermon based on lines of Eliot, about beginnings and ends.

18, Toni didn’t come back, but tracks her down, staying with a gay guy, David Larkin. He goes over there, pleads; she can’t come back, she’s too scared. (He perceives she didn’t quite understand his admission, but doesn’t explain.) He leaves.

19, An imaginary guided tour of his room, on Broadway and 228th. His books, letters, some to famous people, letters never sent, until he imagines one from Kitty and becomes upset.

20, How he was worried about being found out. A frumpy biology teacher with an interest in parapsychology. One day she tested the class with Zener cards. David is careful not to guess correctly—and so gets them all wrong, which is just as odd. She tests him again the next day, and this time he randomizes his answers more plausibly.

21, A string of days. He doesn’t vote. He works on the paper. He goes to a party, probes the host, thinks he overhears familiar names. Has a hangover. A girl comes over for sex, he almost doesn’t make it. He delivers the papers, and Lumumba is upset, feeling insulted, and assaults Selig, his friends joining in.

22, He met Kitty in 1963. He’d become a stockbroker, memorizing all the terms, passing the tests easily. Most of his clients were old ladies, and he gets quickly bored with it, but one was a young girl, Kitty, who he finds to his amazement he can’t read at all. He invites her out, and later tells Nyqvist, perhaps to understand how someone can’t be read.

23, Essay on entropy, how humans fight against the chaos, how evil is entropy, about isolation, about the monogamous fallacy.

24, Second person to Kitty recalling their relationship. Perhaps she has a power? She moves in. She does computer work. He tries to expand her literary education. She doesn’t believe in ESP. He suggests trying various experiments, and persists. They attend a party at Nyqvist’s. DS sees her via Nyqvist, and is astounded by how she sees him: as a stern taskmaster. Then JFK is shot, and he finds a letter from her, she’s left. He writes a letter and confesses everything, but he never hears from her again.

25, He wakes in the hospital. He’s not badly hurt; an intern tells him to leave, they need the bed. A security guard takes him to see Dean Cushing—an old fellow classmate! Cushing implies there may be charges—again Selig, for ghost-writing papers. But no; Cushing merely finds DS sad, pitiful. He offers DS help reforming his life. DS probes Cushing, has another deep experience, then comes out of it—and his power is completely gone.

26, Winter. He visits Judith, imagines meeting Toni in the street for a pleasant reunion. He recalls attending camp in the Catskills, using his power to deftly avoid an aggressive boy boxer. Judith reports she’s no longer seeing Karl. He reflects about everything: what is God’s justice? He doesn’t want pity, just for things to make sense. He must accept. Both Toni and Judith notice how he’s changed somehow. Outside a storm rages, and Judith startles him coming up behind him—something she could never do before.