As noted a couple posts ago, in my series of Star Trek Rewatch posts, I’ve just reread James Blish’s first Star Trek book – published just over 50 years ago! – to note the changes he made from the original script versions of the seven episodes adapted there, or the changes that survived from the early script drafts he received that were changed by the time of filming. I’ve described points about the episodes “Miri” and “The Conscience of the King” in their posts. The other five episodes in the book are annotated here.

As noted a couple posts ago, in my series of Star Trek Rewatch posts, I’ve just reread James Blish’s first Star Trek book – published just over 50 years ago! – to note the changes he made from the original script versions of the seven episodes adapted there, or the changes that survived from the early script drafts he received that were changed by the time of filming. I’ve described points about the episodes “Miri” and “The Conscience of the King” in their posts. The other five episodes in the book are annotated here.

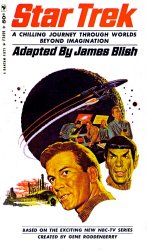

As I mentioned before, Blish wrote short story versions of these episodes from scripts, often early drafts of scripts that differed in substantial ways from the final shooting scripts, and did so without having seen the show himself — this was a time before the show was seen in the UK, where he lived. Clearly, the same situation applied to the cover artist of this Bantam paperback, James Bama, who not only casts a greenish glare over everything, but depicts the Enterprise with rocket fire shooting out all three cylindrical sections of the ship!

“Charlie X”

- First, Blish renames the story “Charlie’s Law”, as in, be nice to Charlie or else.

- Blish summarizes scenes as often as he transcribes all the dialogue from some scenes. The early Blish Trek books were slim paperbacks of 130 pages or so, containing short story versions of seven or eight episodes each, and so turning a 50-minute script into narrative with all dialogue intact was not feasible. (Or necessarily desirable; some plot developments are better summarized, in a short story narrative, while in a teleplay such developments *have* to be explained via dialogue.)

- The story explicitly states that Kirk is fond of Rand – a point of possibility that, the producers of the show realized, led to Rand’s character being written out (so the possibility of a romance between them would not interfere with Kirk fraternizing with guest characters)

- Twice in the book Blish calls Uhura “Bantu”.

- Blish has Charlie make all the phasers on the ship disappear.

- He references the other ship’s “Nerst generator” – a term from his own Cities in Flight stories, I recall, since when I first read and reread Blish’s early Trek books, I also read his quartet of “Cities in Flight” novels.

- Blish expands a last-word line from Charlie, p18t: “Being a man isn’t so much. I’m not a man and I can do anything. You can’t. Maybe I’m the man and you’re not”. The script did not include, or omitted, the final line.

- Blish omits the silly scene of the bridge crew turning every device on to challenge Charlie’s control.

- The line about “I have taken my form centuries ago….” Is missing, but Blish has a different mysterious reference, as the Thasian explains why they can’t restore the crew of the other ship: “We could not help them because they were exploded in this frame; but we have returned your people and your weapons to you, since they were only intact in the next frame.” The oddness of the reference has a similar effect.

“Dagger of the Mind”

- Again, Blish tends to summarize scenes rather than transcribe lots of script dialogue.

- No issue here about a planetary force shield, suggesting that the planet’s atmosphere is sufficient deterrent to potential escapees.

- Some lines from the deleted speech by Adams explaining his motives survive here, p37: “I’m tired of doing things for others, that’s all. … Trust mankind to reward me? All they’ve given me thus far is Tantalus. It’s not enough. I know how their minds work. Nobody better.”

- Blish acknowledges the huge air duct but calls it a crawl-space meant for servicing power lines.

“The Man Trap”

- Blish retitles it “The Unreal McCoy”

- Following an earlier script, the planet is Regulus VIII and the characters are named Bierce, not Crater – while Blish describes the encampment is being inside a crater (!).

- Blish uses the term “petachiae” to describe the mottling on the dead man’s face.

- Blish acknowledges that what Spock finds out about the “Borgia root” is only what the Bierces themselves said in an earlier report. (Otherwise, why would the Enterprise have details – and names – for every plant on every remote barely occupied planet?)

- This version avoids the shoot-out with Crater in the broadcast episode; instead Kirk orders both Bierces aboard the ship.

- Again, Blish follows a single character flow story line. Thus, he has none of the side scenes that we saw in the episode, with the creature changing into Uhura’s Swahili-speaking crewman, or the biolab scene with Rand, Sulu, and the silly plant “Beauregard”.

- Blish adds a bit of speculation about why the race died out: “It wasn’t really very intelligent—didn’t use its advantages nearly as well as it might have” referring presumably to the shape-changing. Spock comments: “They could well have been residual. We still have teeth and nails, but we don’t bite and claw much these days.”

“Balance of Terror”

- In this one you can tell Blish, having seen only a handful of early scripts sent to him for this book, and never having watched the broadcast show itself, wasn’t entirely clear about some of the series’ premises. In the opening of this story, as he builds toward justifying the occurrence of a wedding on the Enterprise, he says: “Traveling between the stars, even at ‘relativistic’ or near-light speeds, was a long-drawn-out process at best.” p54.6. Even though at other times he refers to the warp speeds.

- He notes the blandness of the chapel.

- He identified Spock’s homeworld, Vulcan, as a planet of the star 40 Eridani.

- Blish has a nice line describing the Romulan energy weapon fired at the Enterprise: “Moving with curious deliberateness, as though it were traveling at the speed of light in some other space but was loafing sinfully in this one, the dazzling bolt…” I’m guessing this was not a description in the script.

- In Blish’s version, no one has seen a live Romulan – but bodies were found in the first Romulan war and so they are known to be of the “Vulcanite” type – though this doesn’t lessen the dramatic reveal of seeing the Romulans, and how they are “dead ringer”s for Spock.

- Blish understands there would have to be a *sphere* of satellites around the Romulus/Remus system, p59t.

- Technical jargon: Uhura (for some reason it is her) detects what turns out to be the invisible Romulan ship via a “De Broglie transform” and then Spock calculates that the ship is on a “Hohmann D” transfer orbit back to Romulus. Needless to say, not terminology in any version of a script.

- Blish also isn’t quite clear, in this first Trek book, about the relationship between the characters; Spock is a “funny customer”; “his manners are bad by Earth standards”, and no one particular likes him.

- Big plot change: Blish’s story has Kirk take time out to complete the marriage interrupted at story’s opening.

- Also a substantial change: since Blish realizes they’re in a single star system, Spock has noticed a cold comet and now realizes they can use it as a diversion. Not, as in the broadcast show, does the Romulan ship for some reason fly into it directly. (Still, Blish has Spock find the comet in an ephemeris. An ephemeris of what, all comets in all planetary systems everywhere?? Or for some reason, an ephemeris of comets in this one system? Blish may have known his biology, but apparently had no sense for scale in astronomy.)

- (Also, of course, again, Blish omits all scenes in the broadcast episode on the Romulan ship itself, sticking to a single story line.)

- Kirk uses the comet’s passage between the two ships to accelerate toward the Romulan ship and fire its phasers. Then comes the scene in which the phaser crew downbelow is disabled. Kirk has already sent Spock there, and sees on the intercom screen Spock struggle to hit the phaser fire button.

- And in Blish’s version, both Tomlinson and Stiles die – avoiding the issue, in the broadcast episode, of how Spock managed to save one, but not the other.

“The Naked Time”

- Blish avoids the contamination scene, in which Tormolen takes off his glove and exposes himself to an infection, entirely. Blish has Kirk make some plausible speculation about why the dead members of the observation station behaved the way they did, in response to having some infection (e.g., someone would take a shower with clothes on in a hurried attempt to decontaminate themselves).

- Blish has the planet named some long technical string, and the nicknamed “La Pig”, rather than the Psi 2000 of the script.

- Blish tries to rationalize the idea of the planet’s breakup, and how it would affect the Enterprise orbit, p79t: “As the breakup proceeded, the planet’s effective mass would change, and perhaps even its center of gravity – accompanied by steady, growing distortion of its extensive magnetic field – so that what had been a stable parking orbit for the Enterprise at one moment would become unstable and fragment-strewn the next.”

- There are substantial differences between Blish’s version and the broadcast story, since the latter involved some elements introduced in the last stages of production. In particular: Spock’s breakdown in the briefing room, and the entire time travel sequence at the end, are not here. Nor is Scott’s phasering through the wall to get into the engineering room. Instead, McCoy’s antidote to the disease involves a gas spray into the ship’s ventilation system. Riley recovers in the response to that, and lets the others into engineering himself.

- At the same time Blish has some remarkably implausible sequences in which, Kirk having thrown emergency bulkheads inside the ship, to stop the spread of the disease, has Uhura crawl between the hulls and communicate the McCoy by knocking on the metal in “prisoners’ raps”…! The crews’ communicators don’t work inside the ship?

- Instead of Spock’s breakdown and recovery seen in the broadcast version, in Blish’s story Spock experiences a “general malaise” and excuses himself to his quarters. At the end of the story, he is heard crooning to himself in his cabin and playing some instrument that “nobody else on board could stand to listen to it”.