(This is another essay to become a section of my “memoirs,” to be promoted to a page rather than a post, eventually.)

It’s a truism that once you become an adult and have a career job, no one cares about your GPA (Grade Point Average) in high school or college, or even what college or university you graduated from. (At best the university you graduated from got you interviews with companies who otherwise would have ignored you.)

Still, sometimes a look back at report cards and college grade reports can be interesting, even revealing. (I’ve seen a couple of my Facebook friends quote comments from their earliest report cards, to illuminate or contrast their early performance with their eventual careers.)

And since I’ve saved all my report cards, all the way from kindergarten, I think I’ll show some of them there, and comment about them.

I do have two particular points to make.

- First, the earliest report card comments were generally correct about my later academic performance. At the same time, I did not always excel in subjects that later became my central interests.

- Second, my college records from UCLA and later CSUN showed that my academic performance was dramatically different when I was just attending by rote, versus when I had a goal to reach. A B average at UCLA, and an A average at CSUN.

Kindergarten

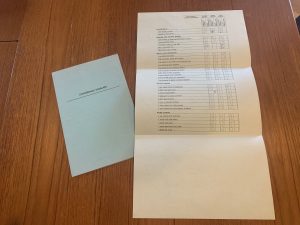

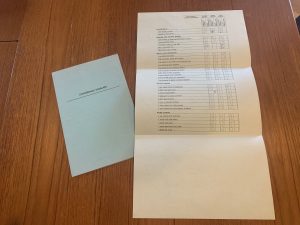

This was in Apple Valley, 1960-61, at Yuca Loma Elementary School, in the windy Mojave Desert. I have two artifacts from this. First, a “Conference Summary” from November 13, 1960; I had been in school a couple months. There’s a long hand-written comment by my teacher, Elaine Kutrosky.

She wrote:

Social Studies—

Mark certainly seems to work hard during our work period. He is usually found working with the blocks constructing something practical, or crayoning or even in the playhouse working hard at being someone. He talks quite well for a five yr. old.

Work Habits—

Mark does concentrate fairly well and usually finishes all projects he starts out. He does need to be reminded to go back and clean up a little better.

I can almost say Mark had some adjustment problems but not quite. He seemed a bit mystified when school started but took our class situation in his stride and is doing fine. Sometimes it is hard for him to realize that sharing is a necessity but after talking with him he understands.

Also at times he need reminding to do his responsibilities. I feel that we should help him assume his responsibilities at school. I think if we both gave him some responsibilities at school and at home would help him realize that responsibilities are important.

And it’s signed by my mother, Helen E. Kelly. (I’m not sure what “responsibilities” referred to exactly. Cleaning up better?)

And I have my report card, or “Kindergarten Growth Report.” The scores are S, for satisfactory, S+, S-, or N, for needs improvement. I got one N, for “I accept responsibility.” I can’t imagine now what that meant. I got S+ scores for being able to relax (i.e. when we took naps on towels laid out on the floor), following directions, speaking well, being polite, and working well alone. (I’m still very good at this last item.)

And I have my report card, or “Kindergarten Growth Report.” The scores are S, for satisfactory, S+, S-, or N, for needs improvement. I got one N, for “I accept responsibility.” I can’t imagine now what that meant. I got S+ scores for being able to relax (i.e. when we took naps on towels laid out on the floor), following directions, speaking well, being polite, and working well alone. (I’m still very good at this last item.)

The one comment from Elaine Kutrosky was “Mark seems to have potential for being a good student.” Note that this time my mother signed it as Mrs. Robert Kelly.

Grade School

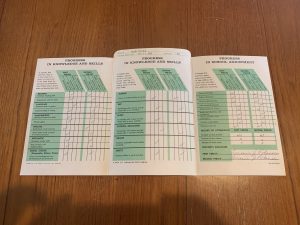

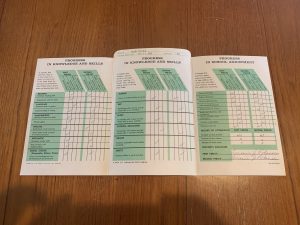

I don’t have a report card from the few months I attended Grant Elementary in Santa Monica, finishing first grade. The next card I have is from the end of second grade (A2 meant advanced 2nd grade, while B2 meant beginning 2nd grade). Throughout elementary school we were graded on “knowledge and skills,” on the one side, and “school adjustment” on the other. The former group included Reading, English, Mathematics, Civics, Science, and other subjects; the latter group covered Effort, Work Habits, and Citizenship.

The possible scores are Outstanding, Very Good, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve, and Unsatisfactory. If these correspond to grades A to F, then in the second period I got As only for reading and spelling. Otherwise I got Bs and Cs, the latter mostly in School Development.

The possible scores are Outstanding, Very Good, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve, and Unsatisfactory. If these correspond to grades A to F, then in the second period I got As only for reading and spelling. Otherwise I got Bs and Cs, the latter mostly in School Development.

This time my father signed the card.

In grades 3 through 6 we got report cards that looked like this. Again, in 3rd grade, I got high marks for reading and spelling, otherwise Bs, except a C in physical education. (As I’ve said elsewhere, I hated the enforced games, like dodgeball.) Yet in contrast to 2nd grade, I improved and got As in Effort, Work Habits, and Citizenship. In 4th grade I got similar marks, mostly As, Cs only in handwriting, music, and P.E. Slight variations in 5th grade.

At the end of the 6th grade – the ultimate judgement of elementary school – I finished with 12 As and 4 Bs. In those last two or three years, I’d always been recognized as one of the top students in each class. (As I recall, given the size of the school, each year’s class occupied two classrooms, about 30 students in each classroom.) But, as I walked out of Vanalden Elementary School for the last time, I understood that one or two other students had higher percentages of As than I did. Oh well; I would never see most of the other students there again.

At the end of the 6th grade – the ultimate judgement of elementary school – I finished with 12 As and 4 Bs. In those last two or three years, I’d always been recognized as one of the top students in each class. (As I recall, given the size of the school, each year’s class occupied two classrooms, about 30 students in each classroom.) But, as I walked out of Vanalden Elementary School for the last time, I understood that one or two other students had higher percentages of As than I did. Oh well; I would never see most of the other students there again.

It’s curious that a couple of those Bs were in science, and music, which later became core interests of mine. What did science consist of in 5th or 6th grade? I don’t recall. And in 5th grade, when I got a C in music, that was the year we got “tonettes,” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tonette), a basic wind instrument in plastic, like a simple recorder (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recorder_(musical_instrument)), which I recall being pretty good at, or at least enjoyed. I suppose I wasn’t that good. (Later, I my 20s, I bought a plastic recorder from a music store at the Northridge Mall and played around with it for years, playing simple tunes from folk music or movie scores. I still have it, but haven’t played it in years.)

Junior High and High School

As explained on my Personal History page for these early years, the key fact about the six grades, from 7th through 12th grades, is that I attended five different schools over those six years. That was a consequence of family moves to Illinois and back, and of course the transition from Junior High to High School.

As explained on my Personal History page for these early years, the key fact about the six grades, from 7th through 12th grades, is that I attended five different schools over those six years. That was a consequence of family moves to Illinois and back, and of course the transition from Junior High to High School.

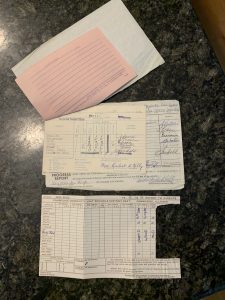

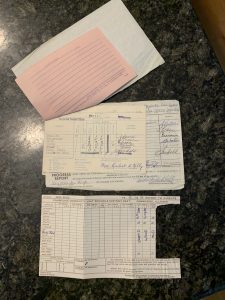

I began at Sequoia Junior High for the 7th grade. I have “Progress Reports” with no grades, just comments. “Tops in class” my math teacher wrote. My English teacher wrote “good student—very perceptive”; my Geography teacher wrote “outstanding”; my homeroom teacher Mrs. Lamberto wrote in October “Use guidance room time wisely—read—study” but by December wrote “a ‘joy’ to have in H.R.—real gentleman of a student.” I also have a separate “Complementary Report to Parents” from my Geography teacher, dated 11/17/68, saying “Mark does very fine work.”

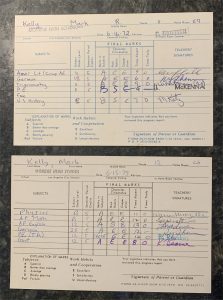

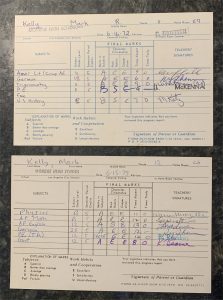

I have two report cards, one with four As (English, Geography, Math, Winds [music, beginning clarinet], one B (in wood shop), and one C (Phys. Ed.). The second with the same subjects, my grade in English fallen to a B, my grade in shop, now drafting, an A, and my grade in P.E. a D(!) – this was when we had to throw softballs, and I was ‘uncoordinated.’

I have two report cards, one with four As (English, Geography, Math, Winds [music, beginning clarinet], one B (in wood shop), and one C (Phys. Ed.). The second with the same subjects, my grade in English fallen to a B, my grade in shop, now drafting, an A, and my grade in P.E. a D(!) – this was when we had to throw softballs, and I was ‘uncoordinated.’

And then a mid-school-year transfer to small town Illinois, to Cambridge Community Schools. I have one report card. Mostly As, but a B in arithmetic, and in vocal music (I don’t remember that class at all), and in Phys Ed, yet an A in instrumental music, even though, as I’ve written elsewhere, the move promoted me into a class of students with more practice learning instruments than I’d had, and I felt I never caught up, was always a minor 3rd rate performer.

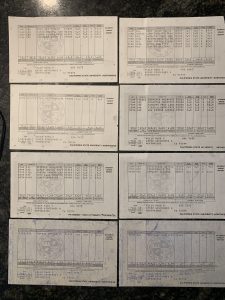

And then Glen Crest Junior High School, in Glen Ellyn IL, for one year. A school that used numbers rather than letters. I got 5s in Social Studies, Science, and Math; 4s in other subjects except (of course) a 3 in Physical Educ. My conduct was Satisfactory in all cases.

And then to Glenbard Township High Schools, for two years. I attended Glenbard East (https://www.glenbardeasths.org/). At the end of these two years, I got 5s in geometry, geography, freshman science, and chemistry. 4s in most other subjects including English, algebra, health (this was sex education), concert band, and driver’s ed. (We had driving simulators, in class, and then drove real cars out on the icy-slippery local streets.) And P.E.

And then to Glenbard Township High Schools, for two years. I attended Glenbard East (https://www.glenbardeasths.org/). At the end of these two years, I got 5s in geometry, geography, freshman science, and chemistry. 4s in most other subjects including English, algebra, health (this was sex education), concert band, and driver’s ed. (We had driving simulators, in class, and then drove real cars out on the icy-slippery local streets.) And P.E.

And then back to California for the last two years of high school, and James Monroe High School in what was then known as Sepulveda, now North Hills (either way, a 91343 postal zone district of the city of Los Angeles). I was doing really well in high school in Illinois, but the high school in California didn’t quite trust those grades, and so didn’t enroll me in as many advanced placement classes that I might otherwise have been enrolled in. Thus, for example, I had no science course in the 11th grade, when ordinarily I would have taken biology; so I never had a biology course in high school. In my first semester I had Advanced algebra/trigonometry, US History (which as I’ve described wasn’t a comprehensive course, but rather a series of 10-week studies on particular topics), German, and typing. And P.E. I’ve discussed the significance of the typing class, even though I got a B; As in the first three, a C in P.E.

My final high school marks, in June 1973, were better. I got As in physics, AP math, AP English (that memorable course with Mr. Eugene Friedman, who in addition to having us read classic novels and plays gave us weekly quizzes on current events via Newsweek Magazine, who had a monthly soiree at his house, on Louise Ave., for his students), and a credit for P.E. because Mr. Friedman had worked with the P.E. teacher to have me work as Friedman’s assistant instead of attending P.E. class.

My final high school marks, in June 1973, were better. I got As in physics, AP math, AP English (that memorable course with Mr. Eugene Friedman, who in addition to having us read classic novels and plays gave us weekly quizzes on current events via Newsweek Magazine, who had a monthly soiree at his house, on Louise Ave., for his students), and a credit for P.E. because Mr. Friedman had worked with the P.E. teacher to have me work as Friedman’s assistant instead of attending P.E. class.

I graduated 40th in a class of 1000.

And so my high school marks were high. As described in my Personal History for this era, I took the PSAT, did well, interviewed with CalTech and MIT, and ended up at UCLA.

IQ test

In the 11th grade, after scoring well on the PSAT, one of the things that happened, in addition to being summoned and recognized by the college counselor, was that I was pulled out of class one day for a private session with some visiting official, who gave me what I gather was an IQ test, or some test about identifying special students. I don’t know; I never heard the results. I do remember a couple particular things about the test.

First, one part was a page of simple arithmetic problems. I started at the top and worked my way down. The instructor said, the ones at the bottom count more. Feeling manipulated, I determinedly kept working them in order. And the time ran out, I didn’t finish the entire page. What was being tested here?

Second, another part was that I was given a blank page and asked to draw a human. I can’t sketch for beans, but I tried to do something, and what I realized was that I was using just the upper left corner of the sheet to draw and small figure – not the entire page, with a large sketch centered in the middle. Was that what was being tested?

As I said, I never heard anything about the results of this test. Presumably I was not identified as any super-extraordinary student.

College Entrance Exams

I took the Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test, PSAT, sometime in 11th grade (as discussed in my Personal History essay). I scored 61 verbal, 73 math. According to the booklet that accompanied my results, those corresponded to about 95 and 98 percentile of all juniors who later entered college (and higher for all juniors). I was among the top four scores at my high school. This is what attracted the attention of the college counselor/AP English teacher, and got my photo on the front page of the Valley News and Greensheet, along with all the other 11th grade high-scorers in the San Fernando Valley (population at the time about a million).

I took the Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test, PSAT, sometime in 11th grade (as discussed in my Personal History essay). I scored 61 verbal, 73 math. According to the booklet that accompanied my results, those corresponded to about 95 and 98 percentile of all juniors who later entered college (and higher for all juniors). I was among the top four scores at my high school. This is what attracted the attention of the college counselor/AP English teacher, and got my photo on the front page of the Valley News and Greensheet, along with all the other 11th grade high-scorers in the San Fernando Valley (population at the time about a million).

The PSAT doubled as a test for the National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test (NMSQT). I don’t remember the details of that program; I think it depended on the college you went to, parents’ income, and so on. Since I went to nearby UCLA, where the tuition was something like $200 per quarter (three quarters a year, not counting summer), I didn’t qualify. So I never got any kind of scholarship.

Then in 12th grade I took the SAT, Scholastic Aptitude Test, which is used by the colleges you apply to, along with your high school GPA, and in some cases personal interviews (as I had with representatives from CalTech and MIT). And, optionally, you take various Achievement Tests in particular subjects.

You can retake some of these tests, but from the paperwork I have, I only took the SAT once. Verbal 650, math 780; 98 and 99 percentiles among all students, 95 and 99 among college bound students.

I took several Achievement Tests, a couple of them twice. Math 2: 760 the first time, 800 the second time. English: 710. Chemistry: 710. American History (why did I take that? I never had a decent history course in high school. Maybe it was required.): 460.

Some six years later, as I enrolled at Cal State Northridge for a Master’s Degree (which I didn’t finish), I took the GRE, the Graduate Record Exam. There were three scores, for verbal, quantitative, and analytical. I scored 760, 790, and 770.

UCLA, 1973- 1977

I’ve said this many times in various places, that attending UCLA, living at home with my parents and younger kids, commuting to school over those four years, was the worst situation I could have been in. Parents: sent your kids away to college. Let them live on their own. That’s as much a part of the college experience as taking university courses. Whereas I was stuck at home, with three younger noisy siblings; my four years at UCLA, driving there every day from home, were to me an extension of high school.

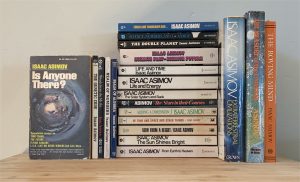

At UCLA, I did OK. My initial ambition was to study astronomy, my early passion. But an astronomy major entailed studying physics for the first two years, and I did OK only up to a point. Many people, I’ve understood from some of my Facebook friends, have a point in their studies, especially in physics or math, where they suddenly don’t “get it.” Their intuitive understanding of the subject disappears. (This evokes a deep theme, the idea that perception of reality is limited or enabled by one’s native intelligence, one that I’ll explore in my book about science fiction.) For me, it was the third quarter of my sophomore, quantum physics, Feynman diagrams, and I just didn’t get it. I couldn’t work my way through them. I got Cs, even a D, in those courses.

I didn’t have any clear goal about a career. At the end of my sophomore year, I changed major to math, where I’d done better. As in any major, certain core courses are required, and beyond them are various options, specific courses of study one can select from; every field has specialties. I did better in some core courses than in others, and so I gravitated toward the fields I did best in. I hit a wall with what’s called “analysis,” which is the justification from first principles of calculus. It involved much study of infinitesimals, and asymptotes, and I struggled. On the other hand, I liked, and did well, in math classes on discreet topics: number theory (elementary topics there involve prime numbers and the Fibonacci sequence), linear algebra, group theory especially, and so on. I moved from getting Cs in math classes – my major! – to getting As.

I didn’t have any clear goal about a career. At the end of my sophomore year, I changed major to math, where I’d done better. As in any major, certain core courses are required, and beyond them are various options, specific courses of study one can select from; every field has specialties. I did better in some core courses than in others, and so I gravitated toward the fields I did best in. I hit a wall with what’s called “analysis,” which is the justification from first principles of calculus. It involved much study of infinitesimals, and asymptotes, and I struggled. On the other hand, I liked, and did well, in math classes on discreet topics: number theory (elementary topics there involve prime numbers and the Fibonacci sequence), linear algebra, group theory especially, and so on. I moved from getting Cs in math classes – my major! – to getting As.

I notice, riffling through my files, that on my SAT tests I identified my career goal as “doctorate.” My early ambitions to become an astronomer would obviously have indicated that direction, since there are few industry jobs for astronomers. During these years at UCLA, I had to recalibrate. For a time I considered becoming a teacher, say, a high school math teacher. Even then, I felt I was good at explaining things. (….whatever happened to that?)

As I look at my “Undergraduate Student Record Card” (shown here), i.e. my grades while in UCLA, I recall another issue about attending college. Having taken AP, Advanced Placement, courses in high school, I had license to skip introductory college courses in those subjects. In retrospect, bad idea: college courses are faster and more rigorous than those in high school. My first quarter at UCLA, I took math 11C – skipping 11A and 11B – and got a C. Similarly physics; I got a B, then a C in second quarter. I should have started from the beginning, in college.

CSUN, 1980- 1983

Here we come to the second point in my introduction. After working a non-technical job for a couple years after finishing UCLA, I rallied myself and decided to go back to school, this time in the more useful field of computer science. Part of the timing here is that I had to have supported myself for a couple years before I was eligible for student loans and work/study. Thus, I quit my day job and lived, for two full years, on student loans and a part-time job on campus. I took a full load of courses in each of four semesters, over two years. I enrolled at first for a second bachelor’s degree. Having the first such degree, I was exempt at CSUN from various “breadth” requirements, courses outside your major required to broaden your horizons. So I only had to take computer science courses, and some peripheral engineering and philosophy (i.e. formal logic) courses, to satisfy the requirements for a B.S. in computer science. I also took a few math courses, some of them perhaps required (e.g. combinatorial algorithms) but some perhaps just for fun.

Anyway, for four semesters running, plus one summer session, I got straight As. In 22 different subjects. (Some were small courses like labs or 10-week intros to old computer languages like Fortran and Cobol.) Of course, there’s a substantial difference between a UC school and a Cal State school; the Cal State campuses are middle-tier universities, somewhere between community colleges and the top-tier UC system. So it would always have been easier to get straight As at Cal compared to UC, whatever my determination.

By Spring of ’82 I’d decided to pursue a career job, and got much assistance from campus programs to bring corporate recruiters on site. But I’d also decided to continue school, and changed my intentions from a 2nd bachelor’s degree (which I therefore did not receive) to a master’s degree. I started work in June ’82, but kept taking courses in the evenings for another year and a half, three semesters. The Cal State colleges, unlike University of California campuses, served many students who worked during the day and took classes at night.

But it was a lot of work. In Fall ’82 I enrolled in two full courses and one prep course on how to develop a thesis. Too much work. I dropped the latter, got an A in one of the others, but only a B in the third—only because I didn’t complete the special project required for the A. I took one course in Spring ’83, and got an A. And then I took one class in Fall ’83, one which required writing two or three big papers, and was not keeping up—so I dropped it and got an incomplete. Ironically, that last course was in “software engineering,” i.e. the process by which industry software projects are planned and managed – exactly what my day job was all about!

But it was a lot of work. In Fall ’82 I enrolled in two full courses and one prep course on how to develop a thesis. Too much work. I dropped the latter, got an A in one of the others, but only a B in the third—only because I didn’t complete the special project required for the A. I took one course in Spring ’83, and got an A. And then I took one class in Fall ’83, one which required writing two or three big papers, and was not keeping up—so I dropped it and got an incomplete. Ironically, that last course was in “software engineering,” i.e. the process by which industry software projects are planned and managed – exactly what my day job was all about!

So I finished with a cumulative GPA of 3.95, without a degree. But the courses at CSUN had served their purpose. I had a full-time professional job, one that I kept, with variations in assignments, for 30 years.

Certificates and Awards

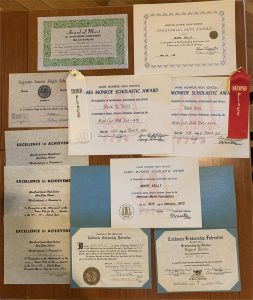

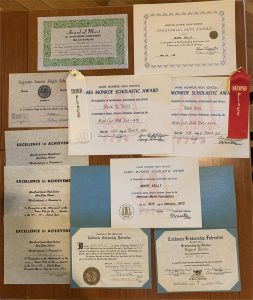

If in Boy Scouts you got lots of badges and patches, so many that you need a vest-like “patch jacket” to display them all, but no paperwork, in school and college (and later at work) you lots of paperwork in the form certificates and awards that one could frame and put on your wall (but no badges). Here are some photos of a bunch of them from Junior High and High School.

If in Boy Scouts you got lots of badges and patches, so many that you need a vest-like “patch jacket” to display them all, but no paperwork, in school and college (and later at work) you lots of paperwork in the form certificates and awards that one could frame and put on your wall (but no badges). Here are some photos of a bunch of them from Junior High and High School.

The earliest, at upper left, is for participating in an “Elementary School Mathematics Field Day,” in May 1967, i.e. near the end of 6th grade. I don’t remember this.

The next, upper right, is an “Industrial Arts Award” in 7th grade for having done well in that drafting course. I suppose my father was tickled, him being an architect.

The next two items, with ribbons, were for participating in Math Club test, the MAA; again, I don’t remember the details. I was 3rd in my school one year, 2nd the next.

The three at the bottom were consequences of my having scored well on the PSAT, and having become a finalist for the National Merit Scholarship and a life member of the California Scholarship Federation. My membership in that federation never had any consequences beyond receiving these certificates.

And the ones along the left are various “service” and “honor roll” certificates for having had high GPAs in 7th and 8th grades.

I’ll have a bunch more analogous certificates and awards when I summarize my professional career at Rocketdyne.

Another IQ Test

A few years later I took another IQ test, this one self-administered. That may sound odd, but the test was deliberately designed to be extremely difficult and not open to the casual looking up of answers. It was called the Mega Test – it even has a Wikipedia page, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mega_Society — and was designed to discriminate among those who score highly on standard IQ tests. (I seem to recall that I did take a standard IQ test at some point, and scored 132? But I have no record of it.) The test was published in Omni magazine in early 1985, and readers were invited to submit their answers, taking as much time as they needed to work them out, for scoring. I spent a considerable amount of time—I have a folder full of several dozen sheets of paper with calculations and diagrams trying to work out the answers – submitted my answers, and got a scoresheet in return dated May 23, 1985. Of the 48 questions, I answered all but 7, but I got only 31 correct and so was incorrect on several I thought I’d figured out.

A few years later I took another IQ test, this one self-administered. That may sound odd, but the test was deliberately designed to be extremely difficult and not open to the casual looking up of answers. It was called the Mega Test – it even has a Wikipedia page, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mega_Society — and was designed to discriminate among those who score highly on standard IQ tests. (I seem to recall that I did take a standard IQ test at some point, and scored 132? But I have no record of it.) The test was published in Omni magazine in early 1985, and readers were invited to submit their answers, taking as much time as they needed to work them out, for scoring. I spent a considerable amount of time—I have a folder full of several dozen sheets of paper with calculations and diagrams trying to work out the answers – submitted my answers, and got a scoresheet in return dated May 23, 1985. Of the 48 questions, I answered all but 7, but I got only 31 correct and so was incorrect on several I thought I’d figured out.

Anyway, I got 31 of 48 correct, corresponding, according to their booklet, to an IQ of 162.

I can’t find the test itself anywhere online, though there’s a similar one here, http://miyaguchi.4sigma.org/hoeflin/ultra/ultra.html. But I’ll photograph the photocopies I have of the test I took, along with my answers and results. (I’ve inserted this photo at especially high resolution so you can read all the original questions.)

I never bothered to apply to Mensa (or similar organizations); I wasn’t interested in joining a club, I just took the test for fun, as a solitaire puzzle to see how much of it I could figure out.

Final Point

Of course, there’s an obvious third point to make: there’s not a high correlation between high grades, or a high IQ, and success in life. I had a decent career, earning a bit over six figures a year by the end of it (in 2012), but I didn’t move into management or become any kind of expert. Outside work I built some databases, wrote some reviews, created a couple websites. I even won a major science fiction award. But I’m not the least bit famous, and it’s unlikely anything I’ve done will be remembered once I’m gone.