Here’s another autobiographical post, probably repetitious with some of the others, about specific events or circumstances that triggered interests or beliefs, some brief, some that have lasted a life. 3500 words just today—a draft.

Science Fiction

There are several phases to this interest, some of which have waxed and waned. An essential point is that my interest has been to particular forms of science fiction, mostly literary, and not to peripheral forms that most people think of they think about science fiction, including most sf movies, comic strips, and superhero movies. And we don’t use the abbreviation sci-fi; that’s a term of ignorance or disrespect.

How did it start?

- A couple specific triggers. One was a comic strip in Boy’s Life magazine, the boy scouting magazine that I got for the few years I was in Cub and Boy Scouts, called Space Conquerors! It was the epitome of space opera, with four astronauts in a flying saucer whizzing around the galaxy and encountering bizarre aliens. This article from Black Gate, https://www.blackgate.com/2018/11/07/space-conquerers/, has several samples I remember vividly, especially the panel part way down that shows people dissolving into goo—very impressionable to an 8-year-old.

- When I tossed my collection of the magazine years later… I snipped out all the Space Conquerors strips and still have them in a folder in my file cabinet.

- At about the same time or maybe a bit later, when I was 10, the neighbor boy Jeffrey Strausser mentioned the TV show Lost in Space to me and was surprised we weren’t watching it at my house. This must have been Fall 1965 and the show had been on a few weeks. At his house one afternoon we watched an old 1950s movie called Invaders from Mars, a moodily lit sf/horror movie about a boy who realizes aliens have landed and are replacing all the adults in his town, including his parents.

- I managed to watch Lost in Space at my house (it was a prime time show, in the evenings) once in a while, though we had only one TV and I did not always get my way. Friends at school during recess liked to play robot (“Danger, Will Robinson!). (It wasn’t until years later, actually the early ‘70s after we’d returned to California, that I saw the essential opening episodes that show the Jupiter II departing Earth and crash-landing onto their planet.)

From the Ridiculous to the Sublime

- Being enthused by Lost in Space – a show aimed at kids, and a show that got increasingly absurd through its run — made me attentive to ads for a new science fiction show—for adults, they stressed—to debut in the Fall of 1966. That was Star Trek, which I managed to see most episodes of over its three years, and is its own subject for a different page here.

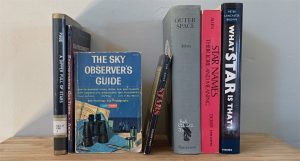

- Then there’s a curious sequence of links from these relatively primitive TV shows, and my parallel interest in astronomy, to discovering literary science fiction.

- Another astronomy book I ordered through the Scholastic catalog at school was Environments Out There, by Isaac Asimov, published in February 1967. Because I liked that, I ordered another Asimov title through the catalog, this one called Fantastic Voyage, which turned out to be a novelized version of the script for the 1966 science fiction movie (that I didn’t see until years later).

- In the Fall of 1967, while I was at junior high school, book fairs were held in the cafeteria where stacks of books were laid out on tables for immediate purchase. Among the books I bought was Star Trek, by James Blish, a collection of short stories based on scripts from individual episodes of the show.

- About a year later the film 2001: A Space Odyssey went into wide release, and though my family generally never went to the movies, I asked to be taken to see this one, and managed to see it twice. I had already bought the book—it came out in July 1968—and so had no trouble following the film.

- These were the initial triggers. Lost in Space was kids’ stuff (though I saw it at such an impressionable age, I retain a nostalgic fondness for parts of it), Star Trek was adult but old-fashioned, and 2001 was a work of art. Within three years, serendipitously, I’d progressed from the ridiculous to the sublime.

From the Visual to the Literary

- Then come the links.

- Because of Isaac Asimov’s film novelization, I moved on to actual Asimov novels and stories.

- Because of James Blish’s Trek adaptations, I discovered actual Blish novels and stories.

- Because of Arthur C. Clarke’s novel and film script (both, in a sense, cowritten with Kubrick), I discovered other Clarke novels and stories.

- In April 1969 Ballantine re-issued five Clarke books, including Childhood’s End, with cover illustrations of various spaceships obviously influenced by those in 2001. Because they were published by Ballantine, I trusted Ballantine for other writers, writers I hadn’t heard of. One of the first of those was… Robert Silverberg, whose collection Dimension Thirteen was published in May 1969. (And which I bought at the supermarket in Cambridge, Illinois.)

- I joined the Science Fiction Book Club, in part to get a hardcover of 2001, and also chose early selections by Asimov and Silverberg.

- Even though the first Silverberg books I bought were early works before his full flowering in the late ‘60s/early ‘70s, it was clear to me that he was a level or two above Asimov, Clarke, and Blish, who’d begun their careers two decades before; Silverberg had a literary background and wrote more sophisticated fiction, in terms of prose style and adult themes.

From the Casual to the Current

- I found plenty of books to buy and read for the next few years, though high school, using chains of associations by author or by publisher in many but not all cases. For the most part I was reading paperback editions of novels and story collections that had first been published years, sometimes decades, earlier, by writers who first published in the 1940s and 1950s. Silverberg’s books, along with some anthologies of annual best stories of the year, were the closest I got to what was being published contemporaneously. (The late ‘60s was the era of the “New Wave” in science fiction, but I was only dimly aware of that, as a still casual, not-quite random reader of the genre.)

- Then in the Fall of 1973 I began college at UCLA, and as described elsewhere, discovered A Change of Hobbit bookstore. It was significant because the store got, systematically and reliably, all the new books published each month. And because they sold the magazines, including the newsletter Locus, then a twice-monthly newsletter stapled and mimeographed.

- Through Locus I suddenly became aware of what was going on in science fiction right now. Not just reviews of new books, but news about books authors had just sold to publishers that wouldn’t be out for a year or two. And more significantly, news about what books and stories were being nominated for, and winning, the then two major science fiction awards, the Hugos (presented by fans) and Nebulas (presented by professional writers).

- This provided a focus for paying attention to current books and stories (mostly in the magazines, like Analog and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which I’d started buying in late 1969), and even playing along. That is, I could read the magazines, and many of the current novels, and decide for myself which ones were best and compare mine to results of the awards, and also to selections in those “best of the year” anthologies, of which at the time there were two, one edited by Terry Carr, the other by Donald A. Wollheim.

- The first year I did this seriously was 1973. That is, by the time the awards ballots were announced in 1974, and Carr’s and Wollheim’s volumes were published in 1974, I had already read virtually all of those selections. I eventually read most of the nominated novels and stories from 1972 and before, back into the 1950s, but they were history; I hadn’t become keyed to current events until 1973.

- And then, reading Locus every month (or couple weeks, its schedule was irregular then), I saw Locus had its own annual poll, and annual recommended reading list, compiled explicitly to influence the Hugos, according to the editor, Charles N. Brown. He even invited his own readers to submit their lists of favorite novels and stories! And so, by 1975 or 76, I started doing so. I became a reliable correspondent, often sending lists of stories I’d liked along with paragraphs of commentary. In 1980, I noted in my journal, the short fiction categories of the recommended reading list were credited to Terry Carr, Gardner Dozois, and me.

- And this went on for over a decade before one day Charles Brown called me up on the phone one day and invited me to write a monthly review column for Locus magazine.

- This era that began in the early 1970s was when my tastes matured and I discovered so many writers whose techniques and subject matters were superior and deeper compared to the traditional classic SF writers like Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein. Silverberg was the first; then there were Le Guin, and Bishop, and Dozois, and Effinger, and Malzberg, and Wilhelm, and Wolfe. Earlier writers I’d missed, like Ballard. This continued for a quarter century, as I followed the field closely, discovering important new writers just as everyone else did (Bear, Benford, Willis, Gibson, Sterling, Robinson, Egan). My tastes were “progressive” in the sense that I welcomed novel styles, ideas, and approaches – the new is what science fiction is about! — as opposed to “conservative” writers and readers who required simplistic beginnings, middles, and ends, clearly defined good and bad guys, simple-minded battles of good vs. evil translated into space opera.

Leaving Visual SF Behind, Mostly

- Which is a nice lead-in to my disdain for virtually all TV and movie science fiction. I retain nostalgic fondness for the original Star Trek, and even for Lost in Space, but that’s because I was in my pre-teens when I first saw them, and everything you’re exposed to in early life leaves a life-long impression. I watched the later Trek series Next Generation religiously when first broadcast, and it was fine, but I’ve never bothered to watch it again. I’ve not watched any of the other Trek series at all, and I’ve not cared much for the Trek movies. My general issue with all of them is that their themes devolve into soap opera or politics: does Spock die, or live?; Federation vs Romulans and/or Klingons. The best original Trek episodes were those that involved meeting something unknown, and dealing with it, trying to understand it, be willing to change from the experience. That central theme has vanished from all the later variations of Trek—possibly because TV changed, given to seasons with story arcs, rather than individual episodes that can be seen in any order, each with a premise and a conclusion. (I think this reflects why I’ve always preferred SF short fiction rather than novels, let alone series of novels that just keep plot churning without ever reaching any kind of conclusion.)

- History has validated 2001: A Space Odyssey as a great film, a work of art, and the most profound science fiction film of all time. That is in part because how newbies react to it: it’s slow, it’s confusing. No, it’s not; it takes understanding; it’s brilliant because it does things differently than anything before it, which is partly what defines a classic. I was lucky to have seen it at an early age (13) and had read the book.

- The only other science fiction film I’ve liked well enough to have bought several DVD/Blu-Ray versions of over the years is Blade Runner, from 1982, and even then I have a slightly mixed feelings about it. I love the music, the visualization of its future, the oddly mannered, poetic dialogue, and the thematic ambiguity of the difference between humans and replicants; I cringe at the too numerous gratuitous moments of physical violence.

- In recent decades I don’t bother to see most science fiction films. Even though for years I procured and posted Gary Westfahl’s film reviews for Locus Online, I never saw the majority of the films he reviewed myself. (Partly for the reasons he expresses in his reviews, generally the formulaic result of virtually all Hollywood films—films and TV are all so much more alike each other than are the literary works of the best writers.)

- There are some good tries and obscure near-misses, from Solaris to Contact to Interstellar, and I’ll grant that recent films like Annihilation and Arrival are very good. (All one-word titles!) But I’m seldom inclined to see them a second time.

- And TV? The first claimant to an ambitious TV series, following Star Trek, was Space: 1999, with two major TV stars: Martin Landau and Barbara Bain (from Mission: Impossible). The opening card on the debut episode (I vividly remember watching this, with my family, at our home in Sepulveda) identified the location as “The Dark Side of the Moon.” Nonsense; there is no such place (there is however a far side of the moon, which isn’t the same thing at all). And a nuclear explosion that blew the Moon out of its orbit. Again, nonsense; elementary physics.

- What followed? Cheesy shows like Logan’s Run? The Six Million Dollar Man? I didn’t pay them attention. In all these decades, I’ve been impressed only by the recent Battlestar Galactica, well-produced and acted in every way, though still relying on stock SF clichés like space warps and humanoid robots, and with a lame ending. (Lost had science fictional potential for a while, but also suffered from its producers making the story up as they went along, and having no decent conclusion.)

- And movies? The science fiction field was set back 25 years into comic-book terms by Star Wars, in 1977, that fantasized spaceships moving like jet fighters, involved a simplistic good vs. evil battle, and relied on a fantasy pseudo-science “force.” I was astonished when this film took the world by storm, and dismayed that its success led to a dumbing down of science fiction publishing to appeal to readers who liked that film. (Especially at Del Rey, successor to Ballantine.) Its effect wiped out most of the advances of science fiction’s “New Wave” that brought into prominence those early ‘70s writers I was so impressed with. Science fiction became a field of sequels and endless series, alongside the new popularity of Tolkien-inspired fantasy.

And Yet Nostalgia

- Just as I have some nostalgic interest in revisiting the original Trek, and even Lost in Space, I’m fascinated by watching older science fiction movies, from the 1960s and before. (Thus my page on this site of “Skiffy Flix” reviews: http://www.markrkelly.com/Blog/bibliographies-and-reviews/skiffy-flix/.) I find them interesting mostly because they reflect naïve ideas about how the universe works, either because the writers and producers were scientifically illiterate, or because they depicted things dishonestly for the sake of not upsetting audience expectations (as Trek did with its swooshing sound of the Enterprise flying by).

- Later films, from the ‘70s forward, I’ve found less interesting partly because of the cheesy costuming and hair styling of the ‘70s and ‘80s, but also because my sense is that by that time the writers and producers should have known better. Audiences really were getting more sophisticated. I’m sure there have been some fine SF films over the past several decades, but very few that measure up to the best SF novels and short fiction. None that I’ve found interesting enough to rewatch, as I still rewatch those creaky 1950s films. (But I need to think about this, and revisit films of the past five decades. If I have time.)

Keeping Current for a While

- I wrote the monthly column for Locus reviewing short fiction, which entailed reading all the magazines every month (at that time there were three major ones and a couple minor) and the occasional original anthology, beginning early 1988, for three years, then stopped.

- Writing for Locus, the major news magazine of the science fiction field (analogous to the book industry’s Publishers Weekly), gave me some legitimacy as a person; it validated my worth. I could go to science fiction conventions – I’d only done so two or three times before, over 15 years – and walk up to a major writer like Connie Willis, introduce myself, and be greeted with interest. (Of course I tended to approach writers whose work I liked. Obviously I avoided those whose work I hadn’t. So it goes with all associations among writers and editors, in a field with many different flavors of science fiction, political attitudes, and opinions about how stories should be written.) The first convention I attended after starting the column was a Westercon in a blistering hot Phoenix (the convention is held over July 4th weekend), where I actually met Charles Brown for the first time in person, and met Robert Silverberg for the first time. Later that year at the Worldcon, that year in New Orleans, I chanced upon some famous writer—it may indeed have been Connie—and she not only welcomed me, but invited me along to lunch with her, Greg Bear, Kim Stanley Robinson, and someone else, maybe James Patrick Kelly. That was a heady start to the weekend. On the other hand, not all writers are nice or approachable. At the same convention I introduced myself to George Alec Effinger, who’d published an excellent story earlier in the year, and all he did was complain that I hadn’t reviewed his other story, the one published in Playboy. Oh well.

- It was also congenial in those years to be a part of the Locus crew. Charles Brown and two or three of his staff would attend, and there would be a Locus Dinner one night during the con, when we’d all go out to a restaurant and Charles would pay. These conventions usually had dealers’ rooms, and there would always be a Locus table (to sell subscriptions), and so I could drop by there to chat. Furthermore, the big publishers like Tor and HarperCollins would host room parties in the evenings, sometimes open-door but usually by invitation, and anyone associated with Locus got an invitation. Snacks, wine, scotch, more people to meet. I’m not particular extraverted, but again, having Locus creds gave me reason to mix a little and be recognized.

- I stopped after three years due to a combination of fatigue from monthly deadlines and personal matters. The latter passed, Charles hadn’t found a replacement short fiction reviewer by the end of the next year, and so I decided to start up again, in 1992. That ran until the end of 2001.

- (Several 1997 era columns are linked to this mirror of my first webpage, on Compuserve: http://www.markrkelly.com/CompuServeHomepage.html.)

- For the first decade, from ’87 to ’96, I attended the annual World Science Fiction Convention, and twice the annual World Fantasy Convention, the latter a more professional affair with a quite different manner. Beginning 1997 I got more involved with Locus – I launched its website – and started going to more convention, three or four a year. Now I was a web-publisher.

- For purposes of this discussion, though, I ended my monthly column permanently at the end of 2001, partly due again to that fatigue of monthly deadlines, and also because my partner Yeong had moved in and had little patience for my reading and writing. (Reading was for adolescents and single people, he told me.)

- And so the upshot is, once I didn’t have to read for my monthly column, I stopped keeping up. I had read the magazines and original anthologies and kept current with the best stories published, all the new writers, and so on, for nearly 30 years. And then, for the most part, I just stopped, I stepped away. I still bought all the magazines and many anthologies (and I still do), but I didn’t read them except occasionally after some stories had already been nominated for one award or another. Yet some years go by when I don’t get around to reading any of the year’s short fiction.

- I’ve kept up on some current novels over the past 20 years, though again there are some award winners I haven’t read.

- I do plan to visit some of these works of the past 20 years, discovering them belatedly rather as I discovered Asimov and Clarke and the others only years after their works were first published.

Haphazard Decades, with Ambitions

- In the past two decades, I’ve lived with a partner who has no interest in books or reading. And yet, intermittently, I’ve read about as much overall as I did in the ‘90s, discounting all the magazine reading I was doing then.

- In the past five years, since moving to Oakland, I’ve been “retired,” staying at home every day, while my partner goes to work 5 days a week. (Until recently, April 2020, when he’s worked from home given the pandemic.) And so I’ve gotten lots of varied reading done. But not a lot of current SF. My interests have run more to nonfiction in recent years, and to revisiting classic SF. (I’ll explored nonfiction triggers on the Books page.)

- For a couple years now I’ve been revisiting “classic” (1950s and before) SF novels with an eye to re-evaluating them from the light of contemporary understanding of science, contemporary perspectives of social and moral issues. As usual I’ve read a lot more than I’ve posted about on my blog. But my review/summaries of classic SF novels are now appearing every two weeks at Black Gate (https://www.blackgate.com/), which gives me incentive to keep going.

- At the same time, it’s impossible to read/reread all the significant novels of the past 7 or 8 decades of science fiction publishing, and I’m now contemplating how to shift my focus from only classic SF novels, to the most significant works by selected authors over all of SF history. In support of my imagined book about “the intersection of science fiction with ancient and contemporary knowledge,” as I’ve noted elsewhere. Which authors should I focus on? The classics by Asimov, Clarke, Heinlein, sure; but then who. Silverberg. Le Guin. Robinson. Egan. Wolfe. And a few more.