On this page titles are sorted by rating.

Grayling, A. C.. 2013. The God Argument: The Case Against Religion and for Humanism. Bloomsbury. *****

Grayling, A. C.. 2013. The God Argument: The Case Against Religion and for Humanism. Bloomsbury. *****

British philosopher Grayling’s book is a worthy, graceful companion to the relatively incendiary books of the 2000s by “new atheists” Harris, Dawkins, and Hitchens. He provides a reasoned discussion of the pitfalls of the religion and a defense of the life-enhancing alternative, that of humanism. He dismisses the defenses of religious apologists, and defends humanism as based on the best, most generous, most sympathetic understanding of human reality: How faith is held despite evidence, or despite the faith of those with different faiths, just as we dismiss the myths of the Greeks and Babylonians. The classic arguments for God might as well prove Zeus, as the Christian God. The portion of humanity that is not Christian are not, in fact immoral; they do not depend on the Bible and its commandments to understand what is right or wrong. The second half of the book focuses on the positive: the case for humanism. Religion, based on “superstitions of illiterate herdsmen living several thousands of years ago,” deserves no privileged place in society. Humanism is the ethical outlook that says each individual is responsible for choosing his or her own values and goals, and is responsible for living considerately of others. Grayling describes 10 criteria for living a good life, and says the meaning of life is what you make it: loving someone, raising children, succeeding in one’s field; having integrity, being honest. How morality is an objective matter, about our fellow humans, without reference to any deity. If I were to recommend one book to believers who have doubts, or to believers who simply want to understand why nonbelievers cannot accept what believers feel to be the obvious truth of their faith, it would be this one.[Quote of first paragraph: “To put matters at their simplest…”; full discussion]

Harris, Sam. 2004. The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason. Norton. ****

Harris, Sam. 2004. The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason. Norton. ****

Harris was the first of the “four horsemen,” public intellectuals who published controversial books about religion in the years following 9/11. He discusses the incompatibility of rival faiths, and of reason and faith; why beliefs should correspond with the world, and be logically coherent; about the sordid histories of Christianity and of Islam; how US politicians pander to the religious; how issues of morality can be addressed through reason (what the ancients thought is irrelevant); and how [this seems to be the book’s flaw, being tangential] “mysticism” or spirituality is something to rescue from religion. (post)

Shermer, Michael. 1999. How We Believe: The Search for God in an Age of Science. Freeman. ****

Shermer, Michael. 1999. How We Believe: The Search for God in an Age of Science. Freeman. ****

This book complements Shermer’s first, about “weird things” people believe, looking at religious beliefs in the US in broad terms, focusing on surveys and polls of belief in God, the afterlife, and so on, with considerations of Messiah myths and millennial stories. A few examples are dated, but the principles remain. Notable is that the author was a born-again Christian in high school whose doubts about religion never went away. Topics include Time Magazine’s famous “Is God Dead?” article; cold readings; how humans perceive things that are not there; people’s beliefs for why they (or others) believe in God. Shermer reviews the common arguments for the existence of God and provides crisp counter-arguments. Also: intelligent design; The Bible Code; how story-telling led to myths; The Messiah Myth, UFO cults, cargo cults; how the story of Apollonius of Ryana is virtually identical to the story of Jesus; and how the marginalized or oppressed are often attracted to millennial beliefs about the end of the world. (post)

Dennett, Daniel C.. 2006. Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. Viking. ****

Dennett, Daniel C.. 2006. Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. Viking. ****

The most philosophical of the books published in the 2000s by the so-called “new atheists,” this book doesn’t challenge religious claims, but considers how to study religion as a natural phenomenon, as a part of the evolution of human nature, to explore how it arose and to what extent it still plays a role. His approach is cautious, beginning with a justification for why such a study is valuable, despite the offense some of the faithful might take. He reviews the deep roots of religion, with the mind’s agent-detector and “intentional stance” leading to animism, folk religions, and how groups maintain themselves whatever their purpose. Now we have “belief in belief” and belief without understanding, rather like falling love, not subject to rational consideration. Studies can be done about whether religious belief is beneficial, or whether prayer really works; some such studies have been done, and the faithful ignore them. We can say that religion does not inspire morality; more the opposite. Nor are atheists self-centered know-it-alls; rather it’s an error to think belief in the supernatural is required in order to be good. Ethical questions remain about the education of children: author advises teaching them all religions, so they can make informed choices; shielding them from the world leads to toxic religions and terrorism. (post #1; post #2; post #3)

Dawkins, Richard. 2006. The God Delusion. Houghton Mifflin. ****

Dawkins, Richard. 2006. The God Delusion. Houghton Mifflin. ****

Straightforward to the point of bluntness and pugnacity, Dawkins covers familiar issues such as the arguments for God’s existence (weak or implausible) and extends the theme along four “conscious-raising aspirations”: that you don’t have to remain stuck in your childhood religion and should in fact aspire think for yourself and be an atheist; that the power of “cranes” such as natural selection provide a natural understanding of the cosmos; the dangers of childhood indoctrination and such phrases as “Catholic child”; and finally why there should be pride in being an atheist. Individual chapters cover the awe and wonder available in the real universe; the reasons why there is almost certainly no God; what religion is “good” for if anything; how morals do not derive from scriptures; and whether religion fills a “gap” in the brain. The post link here has links to five earlier page with very detailed notes on all these subjects. (post) (Read Reread Aug 2022)

Hitchens, Christopher. 2007. god is not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. Twelve. ****

Hitchens, Christopher. 2007. god is not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. Twelve. ****

Hitchens was an erudite “public intellectual” who wrote and spoke on many topics, and here his life-long simmering irritation with the crazy things religious people say they believe comes to a head. This is the least polite of the four books by the “new athiests” of the mid 2000s, and he’s blunt about spelling out all the things he rolls his eyes at, mixing such examples with personal anecdotes and examples from history. (Critics of the book nitpick his history without addressing its main themes.) He begins with epiphanies from childhood, then summarizes his four irreducible objections to religious faith: it misrepresents the origins of man and the cosmos; it combines a maximum of servility with a maximum of solipsis; it results and causes sexual repression; and it is ultimately grounded on wish-thinking. Religion is man-made, he concludes, and will never die out but: it poisons everything. Chapters discuss how religion killls, is inimical to health, how its metaphysical claims are false, how arguments from design don’t work, how if the Old Testament is a nightmare, the New Testament is worse, how the various faiths have borrowed from each other, and how its beginnings were corrupt. Religions don’t make people behave better, that it may be child abuse, the comparisons with atheist regimes like Stalin’s and Hitler’s are off-point, and concludes by calling for a new Enlightenment, “the study of mankind, of science and literature that enable us to know ourselves and our world.” (post) (Read May 2007)

Coyne, Jerry A.. 2015. Faith vs. Fact: Why Science and Religion Are Incompatible. Viking. ****

Coyne, Jerry A.. 2015. Faith vs. Fact: Why Science and Religion Are Incompatible. Viking. ****

Science is effective for discovering what is true about the world, while faith is not. Coyne patiently belabors this point by describing how science works and how religion cannot withstand even basic questions, like How do you know? And What makes you so sure your faith is right and all the others are wrong? Such questions matter. Coyne considers what science is, what religion is, and how they’re incompatible in terms of method, outcome, and philosophy, and therefore explains why “accommodationism” fails. He considers arguments from faith against science, and explains why they are invalid. And finally considers why this all matters — it matters because reliance on faith can lead to harm, as with child abuse, suppression of research and vaccination, and denial of climate change and numerous scientific conclusions. Also, largely nonreligious nations in Europe thrive. Religion should listen to science, especially about what science has learned about religion. Religion is to science as superstition is to reason. There are five long posts, ending with the one linked here, each containing a summary and then longer raw notes. (post) (Read Jun 2015)

Russell, Bertrand. 1957. Why I Am Not a Christian. Touchstone. ****

Russell, Bertrand. 1957. Why I Am Not a Christian. Touchstone. ****

The core of this book is his 1927 essay, in which Russell explains his position on two grounds: first, the arguments for the existence of God through reason are easily refuted, as he summarizes; second, he identifies several defects in Christ’s teachings (e.g. claims of an imminent Second Coming that never happened, his belief in the everlasting torment of Hell), and finds Buddha and Socrates more worthy of respect than Christ. He understands that most people believe in God because they have been taught from childhood to do so, and people accept religion on emotional grounds, or upon fear of the unknown. He notes how religion’s supposed morality has led to atrocities throughout history, and how advances in social and moral progress across history have been opposed by organized religion. (post) (Read Reread 2017)

van Schaik, Carel, & Michel, Kai. 2016. The Good Book of Human Nature. Basic Books. *** 1/2

van Schaik, Carel, & Michel, Kai. 2016. The Good Book of Human Nature. Basic Books. *** 1/2

Why does the Bible contain certain stories, and not others? Because its stories reflect the concerns of humanity as it transitioned from being hunter-gatherers to settling in villages with the “invention” of agriculture. People no longer knew everyone in their community; new diseases were easily spread; concerns about the family line of distribution of property arose. The stories describe how such problems were solved. With perspectives on the history of the Bible, and how ancient human nature that evolved over hundreds of thousands of years has been overlaid twice, first by cultural evolution that varies from place to place, and then by rational institutions and practices that currently keep the world running, even as those practices can clash with first nature reactions. The entire Bible is covered, though focus on its first five books takes half of this one. (summary of the 30-page introduction) (post)

Onfray, Michel. 2007. Atheist Manifesto: The Case Against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Arcade. ***

Onfray, Michel. 2007. Atheist Manifesto: The Case Against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Arcade. ***

This was a bestseller in Europe in 2005, during the same era the “new atheists” (Harris, Dawkins, Dennett, Hitchens) were publishing their books in the US and UK. Onfray deconstructs the three major Western religions on historic, ethical, and rational grounds, while advocating for a post-Christian secular order, an “atheology,” to replace traditional theology. He discusses how the holy books came about through elementary historical processes; how other books were banned or burned, and the hatred of science impeded Western civilization; how in science the church has been wrong about everything; how the monotheisms’ ideas of paradise align with hatred of women, condemnation of homosexuals and abortion, celebration of castration and other maiming rituals. On Christianity: how in Jesus’ era many made grandiose claims, and stories about heroes born of virgins were commonplace; how the religion itself was the creation of Paul of Tarsus, and thus reflects his neuroses (he hated intelligence and culture). On Theocracy: the three holy books took centuries to find their final form; the idea of worshiping one god was the invention of the Jews to justify their annihilation of rival tribes; clerics and war leaders cherry-pick the holy texts to justify whatever they want. And Islam took the worst parts of the earlier two: chosen people, others are subhuman, the world is binary, no subtlety. Lots of good material here — the author has millennia of history at his fingertips — but there’s almost nothing of the opening theme, about how to create his post-Christian secularism. (Read Mar 2022) (post1; post 2; summary) (Read Mar 2022)

Paulos, John Allen. 2008. Irreligion: A Mathematician Explains Why the Arguments for God Just Don’t Add Up. FSG/Hill and Wang. ***

Paulos, John Allen. 2008. Irreligion: A Mathematician Explains Why the Arguments for God Just Don’t Add Up. FSG/Hill and Wang. ***

A slender and breezy book by a mathematician, dismantling the common arguments for the existence of God. The four classical arguments (first cause, design, anthropic principle, ontology) on grounds of logical incoherence and/or statistical implausibility; subjective arguments (coincidence, prophecy, subjectivity, interventions) on statistical grounds; and four psycho-mathematical arguments (redefinition, cognitive tendency, universality, and gambling). With asides about a personal pseudoscience, recursion, emotional need, Jesus and CS Lewis, a dream conversation with God, and the idea of “brights.” (post)

Paine, Thomas. 2010. The Age of Reason. Merchant Books. ***

Paine, Thomas. 2010. The Age of Reason. Merchant Books. ***

Thomas Paine was one of the founding fathers of the US who, despite claims the founders planned a Christian nation, wrote this set of essays as a passionate denouncement of Christianity. Paine defends his deistic belief — that the obvious magnificence of the universe indicates a creator God — but ridicules the Bible on numerous grounds, and rejects all formal creeds. The striking take-away reading this work now is how easy it was, even centuries ago, for anyone to closely read the Bible, compare its various texts, and perceive its absurdities and historical oddities. Topics include the devious methods by which claims of fulfilled prophecy in the New Testament took passages from the Old out of context (the third section of the book details these exhaustively); the parallels between Christian faith and “heathen” mythologies (e.g. the pantheons of Christian saints and Greek gods); notes how the “word of God” was decided by vote centuries after the texts were written down; how the NT isn’t a history of the life of Jesus, but only a collection of detached anecdotes; the incoherency of the justitifcation for the crucifixion; how the Church deliberately suppresses science to maintain its domination. The second part of the book examines specific implausibilities: the dicey chronologies; how the word Isaiah used for Mary didn’t necessarily mean virgin at all (and how if she were, how was this known?); how the traditional story of Jesus is “blasphemously obscene”; and wonders where the saints who rose out of the graves, in Matthew, went, and why no one else noticed them. (summary; long Wikipedia entry)

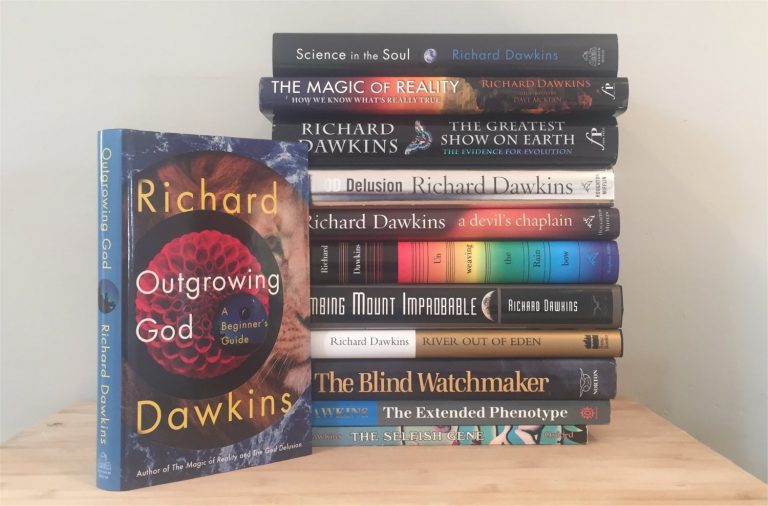

Dawkins, Richard. 2019. Outgrowing God: A Beginner’s Guide. Random House. ***

Dawkins, Richard. 2019. Outgrowing God: A Beginner’s Guide. Random House. ***

A book aimed at younger readers, or adults open to straightforward answers, about why one doesn’t need to believe in God (because, which one?) and shouldn’t believe in the literal truth of the Bible, how myths evolve, how morality is possible without the Bible, and so on. It’s a series of “But what about?” questions, covering how we decide what is good, why there is no designer, how we evolved to be religious, and how natural explanations supplant religious myths. (There are ideas here from Dawkins’ earlier books The God Delusion and The Magic of Reality.) For anyone open to rethinking their childhood beliefs in the light of humanity’s centuries-long examination of the real world, and of the universe, this is a good starting point (along with Grayling’s The God Argument, listed below). (post)

Christina, Greta. 2012. Why Are You Atheists So Angry?: 99 Things That Piss Off the Godless. Pitchstone. ***

Christina, Greta. 2012. Why Are You Atheists So Angry?: 99 Things That Piss Off the Godless. Pitchstone. ***

Blunt, aggressive responses to what the author thinks are illegitimate claims and presumptions of religion, from blaming 9/11 on the gays, to presuming the enormous universe was made just for humans (while accusing atheists of being arrogant), “I feel it in my heart”, atheism is just another religion, how people “need” religion, and on and on. She considers various soft forms of religion and concludes they are as problematic as fundamentalism, because they all rely on some kind of faith, as opposed to dealing with the real world. She provides her “top ten reasons” she doesn’t believe in God, including the inconsistency of world religions, the complete failure of any sort of supernatural phenomenon to stand up to rigorous testing, and of course the complete lack of solid evidence for God’s existence. She reports evidence that you can argue people out of religion, and discusses her methods. (A different approach than Peter Boghossian’s.) (post)

Zuckerman, Phil. 2014. Living the Secular Life: New Answers to Old Questions. Penguin. ***

Zuckerman, Phil. 2014. Living the Secular Life: New Answers to Old Questions. Penguin. ***

How people live their lives without religion, despite the assumptions of many that religion is necessary for morality. (Even though this is obviously not true.) What underlies morality among secular people? Culturization, the ways living with other people leads to principles like the Golden Rule. (The idea echoes E.O. Wilson’s group selection, and Alex Rosenberg’s Core Morality.) In fact, secular people are less likely than the religious to be racist and vengeful, to support torture and oppose women’s and gay rights; there are very few atheists in prisons. Morals are acquired not from lists in books but from the culture in which one lives and the experience in navigating life. Other topics include the familiar evidence that more secular countries score better on measures of social health; that secularism is increasing due to backlash to church scandals, the rise of women in the workforce, the acceptance of homosexuality, and the internet; and the ways secular people deal with various aspects of their lives, including traditions, communities, and life events, with interesting asides about the stages of moral development, and the problematic term “atheist.” (post)

Rosenberg, Alex. 2011. The Atheist’s Guide to Reality: Enjoying Life without Illusions. Norton. ***

Rosenberg, Alex. 2011. The Atheist’s Guide to Reality: Enjoying Life without Illusions. Norton. ***

Author takes the non-existence of God as a given, and explores how therefore to think about reality. Humans evolved to understand the world through stories, but the physical facts explain the nature of reality; the part of physics that explains us has been finished for 100 years. There is no objective morality, but humans have evolved a “core morality” through natural selection and “environmental filtration” (a nice phrase) to handle conflicts within and between tribes. There is no purpose; progress in history is at best local. Core morality with scientism leads to a fairly left-wing agenda: one that is redistributionist and egalitarian. Moral progress comes when people abandon incorrect facts about the world. Author reviews history of science vs. humanists, Snow’s two cultures. [[ I take issue with his claim that since the brain is just activity between neurons, there are no “thoughts” that are “about” anything; this strikes me as the reductionist trap that other authors, like Sean Carroll and Frank Wilczek, avoid. (One could say the same about the Bible, or any other book, as being merely an arrangement of 26 letters, and so meaningless.) And his use of the word “scientism” is different than how it’s come to be used. ]] (notes, with discussion about vocabulary and celestial tea-pots)

Barker, Dan. 2015. Life Driven Purpose: How an Atheist Finds Meaning. Pitchstone. ***

Barker, Dan. 2015. Life Driven Purpose: How an Atheist Finds Meaning. Pitchstone. ***

An explicit reponse to religious superstar Rick Warren’s “purpose-given life”: you find meaning in your interactions with other human beings, and not in some mythology about a god figure in the sky. Sample: Asking, “If there is no God, what is the purpose of life?” is like asking, “If there is no Master, whose slave will I be?” Barker distinguishes between the purpose “of” life and the many kinds of purpose that can be found “in” life. (post)

Bayer, Lex, & Figdor, John. 2014. Atheist Mind, Humanist Heart: Rewriting the Ten Commandments for the Twenty-First Century. Rowman & Littlefield. ***

Bayer, Lex, & Figdor, John. 2014. Atheist Mind, Humanist Heart: Rewriting the Ten Commandments for the Twenty-First Century. Rowman & Littlefield. ***

One attempt among several (as listed on my Principles page) to conceive a more rational, reality-based set of guidelines for living than those to be found in religious texts. Their approach is axiomatic, considering how we can justify any of our beliefs, emphasizing that their conclusions are guidelines, not commandments. Samples: “We act morally when the happiness of others makes us happy.” and “All beliefs are subject to change in the face of new evidence, including these.” The book has a website which has crowdsourced additional guidelines. (post)

- Boghossian, Peter. 2013. A Manual for Creating Atheists. Pitchstone. ***

Boghossian’s first principle is: avoid facts. He calls his methodology “street epistemology” and means engaging in conversations with people about what they believe and why. He distinguishes between religion as a social institution with many admirable qualities, and faith, which he defines as “pretending to know things you don’t know.” He has a chapter devoted to “anti-apologetics” – supplying reasonable responses to the typical challenges from believers about the need for faith and the supposed illegitimacy of science. And he examines the unfortunate effects of a kind of multiculturalism that entails rote acceptance of all points of view about ways of knowing the world, which leads to immunity from criticism of all cultural practices including religion. Academics, he thinks, should support what works, and point out to their students ways of thinking that don’t. (post)

Lee, Adam. 2012. Daylight Atheism. CreateSpace. ***

Lee, Adam. 2012. Daylight Atheism. CreateSpace. ***

Similarly to Grayling’s GOD ARGUMENT, Lee’s first half explains why religious faith is a nonstarter, while the second half explores the benefits of free thought and honest engagement with the world. Topics range from how religion is like fossil fuel, the atrocities religion has wrought upon the world, and how Bible stories describe “a deity who’s petty, insecure, malicious, short-tempered, violent and cruel.” Later, his concept of morality independent of religion as a sort of “universal utilitarianism.” Lee is been a writer on several blogs over the years and ironically many of his essays are better than this relatively short book. Alas, his essay repository at Patheos is gone, but he has a minimalist homepage with his blog archives. He currently writes for OnlySky. (post)

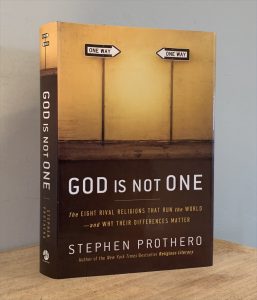

Prothero, Stephen. 2010. God Is Not One: The eight rival religions that run the world — and why their differences matter. HarperOne. ** 1/2

Prothero, Stephen. 2010. God Is Not One: The eight rival religions that run the world — and why their differences matter. HarperOne. ** 1/2

Valuable, useful and irritating by turn, the book first sets out to demolish the bromide that all religions are equally true in some sense. They are not, though they follow similar patterns, crudely, in identifying a problem (sin, pride, suffering) and offering a solution (salvation, submission, awakening). The bulk of the book describes the eight big religions, in order of perceived importance to the world today, beginning with Islam. All religions change over time, subject to political forces and cults of personality; the eastern religions are more philosophies of life than belief-systems; at least one, the Yoruba tribal religion of West Africa, sounds like an over-complicated fantasy novel. The book is spoiled by the author’s antagonism toward those he calls the “angry new atheists”; he is angrier about them than they are about religion. The author is clearly a believer in belief, at the end reminding the reader to be “humble” (and never mind the truth or lack thereof of any of these religions). (post) (Read Mar 2022)

Ehrman, Bart D.. 2016. Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented their Stories of the Savior. HarperOne. ** 1/2

Ehrman, Bart D.. 2016. Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented their Stories of the Savior. HarperOne. ** 1/2

Prolific Biblical scholar Ehrman discovers a new tool for exploring the Bible to deduce which parts are fancy and which might have bases in fact: the fallibility of memory. Especially considering the decades that passed before the gospels were actually written down. Unfortunately he conflates the related idea of how stories told and retold over generations succumb to the human bias toward narrative with matters of memory. Still, there are fascinating discussions here of how the gospels came to be chosen (and rival stories were not), and how some of the stories in the gospels are implausible on their face (the market, the trial before Pilate, the Sermon on the Mount), though again these are matters of storytelling and not about memory per se. (post)

Crane, Tim. 2017. The Meaning of Belief: Religion from an Atheist’s Point of View. Harvard. ** 1/2

Crane, Tim. 2017. The Meaning of Belief: Religion from an Atheist’s Point of View. Harvard. ** 1/2

Philosopher Crane takes issue with the “new atheist” authors, Harris, Dawkins, et al, in their depiction of religion as only about claims of the supernatural (the existence of God; an afterlife). Rather, religion is about identity, about accumulated cultural wisdom about the way to live one’s life, about the ideas of the sacred and the profane. He advises atheists to accept that religion will always exist, and to tolerate believers. (He does not address, or even denies, evidence that religious faith fades with education, and with prosperity.) Discussion at the link includes thoughts about how his ideas intersect with science fiction. (post)

Grayling, A. C.. 2007. Against All Gods: Six Polemics on Religion and an Essay on Kindness. Oberon. **

Grayling, A. C.. 2007. Against All Gods: Six Polemics on Religion and an Essay on Kindness. Oberon. **

Short essays first published as newspaper pieces, about atheists, humanists, and secularists, the death throes of religion, and the alternative of humanism. Pointed, but not as eloquent as his later book The God Argument: The Case Against Religion and for Humanism (2013) (post)

Silverman, David. 2015. Fighting God: An Atheist Manifesto for a Religious World. St. Martin’s/Thomas Dunne. **

Silverman, David. 2015. Fighting God: An Atheist Manifesto for a Religious World. St. Martin’s/Thomas Dunne. **

A blunt book, with little nuance, by the then president of American Atheists, arguing against religion and advocating firebrand tactics to undermine religious privilege. He prefers the word “atheist” to “agnostic” or similar words. He discusses how the “Overton window” can be shifted; legal battles he has fought; rallies he has spoken at; and how all religion is “cafeteria” religion — the religious pick and choose which parts to believe in — and presents a list of questions to believers about why Christianity makes no sense. (E.g. If God is all-powerful, why did it take him six days?) He cheerfully refers to theists as being brainwashed; I think it’s a little more complicated than that. (post)

Loftus, John W.. 2013. The Outsider Test for Faith: How to Know Which Religion Is True. Prometheus. * 1/2

Loftus, John W.. 2013. The Outsider Test for Faith: How to Know Which Religion Is True. Prometheus. * 1/2

A former evangelical Christian who rejected the faith in the 1990s proposes a simple way to think about one’s faith: “consider one’s own faith with the same level of reasonable skepticism believers already use when examining the other religious faiths they reject.” Perfectly reasonable and obvious, yet the author addresses various critiques of the thesis more than he quite explains how one should systemically apply the test, or give examples. Unevenly written, this is another book preaching to the atheist choir, perhaps riding the coattails of the much better writers (Dawkins, Dennett, Hitchens, Harris) of the previous decade. (post)

Lindsay, James A.. 2015. Everybody Is Wrong About God. Pitchstone. * 1/2

Lindsay, James A.. 2015. Everybody Is Wrong About God. Pitchstone. * 1/2

The premise here is that theism has been so discredited — “philosophically, sociologically, and scientifically” — that it is mythology, and atheism is senseless, and we should change the conversation. He understands that most people mean “God” to mean a set of moral values (more than a particular supernatural being), how these attributes are like settings on a mixer board, blended differently in each person [anticipating, or echoing, Haidt], and how a “transcendence” knob turned all the way up equates to faith, which cannot be questioned. The balance of the book is about how to move toward a post-theistic world, citing familiar ideas: education, street epistemology, humanism. Most of this is familiar, and the book is repetitious and long-winded. Written for the choir, as many of these small-press volumes are. (post)