Here’s a book published in 2006. The author, Daniel C. Dennett, is a professor of philosophy at Tufts University. He became grouped among the four so-called “new atheists” of the 2000s, along with Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, and Christopher Hitchens, though despite Michel Onfray’s characterization of the group as “angry,” Dennett doesn’t sound the least bit angry at all, just intellectually curious.

The theme of the book is how to understand religion as a natural phenomenon, that is, part of the social evolution of the human race; it’s not a book about the particulars of religious beliefs or religion’s claims to supernatural knowledge.

Page 15: “For many people, probably a majority of the people on Earth, nothing matters more than religion. For this very reason, it is imperative that we learn as much as we can about it. That, in a nutshell, is the argument of this book.”

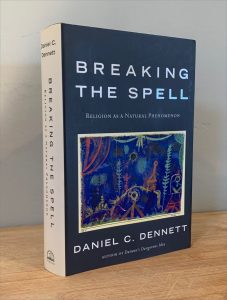

Daniel C. Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (Viking 2006, 448pp) [Amazon]

(I read a portion of this book when it was released back in 2006, then put it down for some reason, and didn’t get back to it until 2013, when I finished it and wrote these notes.

I’ve made a resolution for the next month or so to catch up on posting notes about some of the best nonfiction books I’ve read over the past decade or. I’ve posted notes about many such books, but ironically have put off some of the most important books – because they’re long books and I took thousands of words of notes! It’s a task I put off to try to ‘boil down’ such notes to a couple thousand words, much less a review of a couple paragraphs. So my current strategy will be this: I’ll post the original notes virtually intact, touching them up only for spelling and grammar (and perhaps to reduce paragraph breaks). And while I do that touch-up, which should take more than an hour, I’ll compile a set of key points to put at the top of the post, so that most readers (including me) can get the gist of the book just by reading those.

…As it’s turned out this afternoon, it’s still a chore to touch-up 10,000 words of notes. So for today, here’s post #1, of roughly the first half of the book.)

Key Points (of roughly first half of book)

- Author defines religion, and expresses the need to get past the “taboo” of even studying religion, as if doing so might “break its spell.” But if that is the case, shouldn’t we know? The approach here is to consider religion a natural phenomenon; the book is not concerned with whether God exists or not.

- There are many possible futures of how religion should be integrated into worldly societies; it would be best to anticipate them. To those who have concerns that the study of religion could have harmful consequences, the author thinks he can show such study is worthwhile.

- We can understand many phenomena in terms of reproductive benefit . So what pays for religion? Why do some religions go bad? We must beware simple answers. There are several classes of theories of religion. We can’t know which are right, without study.

- The roots of religion begin with the evolution of the mind, with its agent-detector, memory manager, and so on–and an “intentional stance” that there are other minds with their own beliefs and behaviors. Humans possess 2nd and higher orders of intentionality–thus when someone dies, it’s hard for us to turn off thinking about what the other person would think or fell. Thus funeral ceremonies; spirits.

- This led to ‘animism,’ the idea that everything is alive in some sense, has a soul. Meanwhile humans learned ranges of possible thoughts, like fiction, and hypotheticals. Humans are obsessed by strategic information–who knows what and who doesn’t. We employ imprinting of children; randomness to help make decisions; rituals as a kind of memory-engineering.

- Folk religions became organized religion much as folk music became formalized, especially as agriculture permitted large settlements of individuals and specialization of individuals. Religions would create bonds among groups of people who are not close relatives. An invisible god to whom everyone is accountable helps.

- Once formed, groups tend to maintain themselves, never mind their purpose. Why do people join groups? Groups are subject to defection or betrayal. Perhaps religion solves those issues. And perhaps competition between groups that work at different levels with individual explains some of their features. Or perhaps the market behavior among religions are a way for memes to propagate. People likely don’t think about which group to join; they just pick one. There is a free marketplace of religion in America; those that survive produce a superior product, the doctrines with greatest appeal–e.g. the responsive, fatherly God.

Detailed Notes:

Part I: OpeningPandora’s Box

Ch1, Breaking Which Spell?

An ant in a meadow climbs over and over to the top of a blade of grass—not for any purpose of its own, but because it’s been infected by a parasite, a lancet fluke, that needs to be eaten by a sheep or cow to complete its reproductive cycle.

Humans commonly devote themselves to causes despite their personal reproductive interests—sacrificing themselves for religions, or freedom. How did such ideas arise, and what are they good for?

To understand the nature of religion we need to understand its nature today but also what it used to be. This account will be the next 7 chapters… “I can think of no more important topic to investigate” p7t.

Working definition: religion is a social system whose participants avow belief in a supernatural agent or agents whose approval is to be sought.

There are various neighboring phenomena; e.g. people who are ‘spiritual’ but not religious.

P12m: “What apparently grounds the widespread respect in which religions of all kind are held is the sense that those who are religious are well-intentioned, trying to lead morally good lives…… “

Wouldn’t studying religion ‘break its spell’? Well, some spells should be broken—suicidal cults. Is religion the same as other things people say they ‘need’, like cigarettes or music? Anyway, religion such a big role in the lives of so many people that it’s urgent we know as much about it as we can.

Break the spell? We don’t know. Different religions believe they have the way to truth and peace; who’s right? No way to know until we study.

P17t: “Those who are religious and believe religion to be the best hope of humankind cannot reasonably expect those of us who are skeptical to refrain from expressing our doubts if they themselves are unwilling to put their convictions under the microscope. If the case for their path cannot be made, this is something that they themselves should want to know.”

Part of the issue is the taboo against studying religion at all; it’s been set aside from rational investigation. Some consider it sacrilegious to even think about it. The taboo is like the Emperor’s New Clothes—everyone goes along with not questioning, no matter how obvious things are.

Author intends to break the taboo, and start the project. His philosophical heroes include John Lock and William James. Author is a bright (p21) . [[ my comment at bottom ]]

He realizes that just the notion of a book like this might offend some people. But even atheists have sacred values, e.g. democracy, truth, love.

The approach is to religion as a natural phenomenon—as opposed to supernatural. That is, involving events, structures, patterns etc, that do not include miracles. (Thus we’re not concerned with whether or not God actually exists). No religious person should object; if miracles really are involved, it would take scientific investigation to demonstrate so. Author not concerned with Hume’s project, to find scientific reasons for believing in God. Those arguments will go on. Question is, what is the phenomenon that it affects so many lives so strongly? (But we will address reasons for belief later in the book.)

Ch2, Some Questions About Science

Can science study religion? Author differs from Gould’s idea of non-overlapping magisterial; science can study what religion does. Science itself has gotten better in its methods to filter out biases of observers.

Should science study religion? Well, how can we plan for the future when there are such wildly diverse beliefs in that future—

- Religion is overtaking the Enlightenment and eventually will prevail worldwide;

- Religion is fading and will become merely ceremonial;

- Religions become more like clubs or self-help organizations; belonging is like being a sports fan;

- Religion becomes a private matter not to be discussed, like sexuality;

- Judgment Day arrives; some ascent into heaven; others suffer.

Nobody knows which of these is true, if any; we should apply our skill as a species, looking ahead and planning, in this area as in any other.

Author realizes some feel the study is in poor taste; as if news came in one day that studies showed music was bad for you—that it should be discouraged, limited to an hour a day, etc. Most might think who cares, music is essential, and pursue it anyway. So is religion like music? Why do people feel that way about it? Let’s find out. Some things we like have obvious reasons—sweets. There’s no answer like this for music, or religion.

Wouldn’t it be better to leave well enough alone? Some worry that finding the reason would destroy religion’s positive effects. There’s no evidence of this; in fact, some things—symphonies, poems, etc.—greatly benefit from analysis.

Historically, similar taboos have been overcome, to great benefit—the taboo against dissecting dead humans; the taboo against studying sexuality. On the other hand, some might say knowing too much about sex has harmed society. Maybe, but nowadays there are no secrets; all information is easily accessible.

Still, some might be sure they know what’s right and no study is needed. But what if they’re wrong? Consider if Christmas didn’t exist and a new Harry Potter holiday were proposed, and imagine the opposition, on the grounds that when children learned it to be a lie they would be bitter. Yet the same doesn’t happen with Santa Claus. Such issues should be studied, to find out one way or the other.

To those who distrust this inquiry, as a liberal attempt to deny people their beliefs—that part is right. There is a moral crisis, and the author thinks he has a better way. Let him try to show it.

Ch3, Why Good Things Happen

Author spent some time talking with individuals about what religion meant to them; was impressed by those who were better people for it. Religion can bring out the best in people. But so does enduring a war; that doesn’t mean we should have more wars. And we should ask, e.g., is Islam or Christianity more effective at making people better?

It’s useful to ask ‘cui bono?’, i.e. ‘who benefits?’ when investigating nature. Why would coyotes howl in the night? Why do humans devote so much energy to producing sugar? –because coevolution between plants and animals provided nutrients for animals in exchange for propagating plant seeds.

Digression (p60) about evolution—why do so many Americans deny it? Because their pastors told them so? Because the Bible says so? Author invites reader to go investigate. (p60.7 “they have been solemnly *told* that the theory of evolution is false (or at least unproven) by people they trust more than they trust scientists.” Where do those people get their information? From the frauds of creationists and ID proponents. If your answer is the Bible says so, then you’re not thinking this through and you’re not taking inquiry seriously.)

So, phenomena in nature usually have explanations, in terms of reproductive benefit. Sex, alcohol, money, all can be understood as effects of evolution and co-evolution. (Sex is still something of a mystery – probably has to do with making offspring foreign to the parasites that infect you.) (Alcohol—something about the advantage to the trees that produce the fermented fruit that provides alcohol, which in turns induces pleasurable effects in those who eat them?) (Money is a ‘Good Trick’, something invented time and time again through different adaptive paths.)

So what pays for religion? It’s obviously a huge investment of time and effort by humans. If you think the answer is, God created humans with immortal souls that thirst to worship God, is the answer – then you should be able to rule out alternate explanations.

Some would consider this a non-question, a reductionism. But some religions go bad—and it would be useful to understand the parts and what benefits they provide. Still, this will likely be a complex analysis, so care must be taken in making decisions based on it; as in nutrition debates, most people just want simple answers. The early conclusion about cutting out fat from the diet turned out to be wrong. We can’t rely on evolution-shaped instincts for diet, since our civilization has rapidly changed our environment, and rendered our evolutionary instincts out of date. P74

A Martin’s list of theories

So what might possible theories of religion look like? Consider from an outsider’s point of view, say a Martian. Some religions are designed; others seem to evolve, thus the concept of the cultural replicator, the meme. There are several classes of theories about religion:

Sweet-tooth theories: Our bodies respond to something that religion provides in intensified form, analogous to our tastes for sweets, drugs, etc. Why would such a ‘god center’ evolve? Maybe some people have it and others don’t, like the distaste for cilantro.

Symbiont theories: religions are parasites of sorts that survive by leaping from human host to human host, regardless of whether their effects are beneficial or not. (Most people assume their own religion is benign, but suspect others are toxic; but you can’t tell from the inside.) P86m: “It is well known that the parent-offspring link Is the major pathway of transmission of religion. …” (But simply trying to break this link, as in the Soviet Union, had dire consequences.)

There are also sexual-selection theories—

Bower: like a bower-bird’s bower, religion is a way of showing off fitness to attract mates, similar to the idea that music serves this purpose.

Money theories: religions develop because they serve their communities well, either as a whole society, or perhaps only a controlling elite. This is sort of a group-selection idea.

Pearl theory: maybe it’s simply a by-product of something else; it’s not ‘for’ anything.

Many readers may think they know which theory (or theories) are right, but no one can know without research. Some people assume religion is the obvious response to the fact that God exists—but this doesn’t explain all those other religions; why have they gotten it wrong?

Appendix B discusses how science serves as an objective basis for thinking about these theories. (Why science isn’t just another religion…)

[[ My private guess is: partly ‘sweet-tooth’ and partly ‘money’. Religion satisfies the part of the brain that constantly searches for explanations of the world, the part that is also susceptible to superstitions of all sorts; and socially it serves both as a community bonding force, an element of tribalism, that makes individuals more trustworthy because they have ‘submitted’ to a set of beliefs that overrides all individual concerns. The last idea is why most people think less of an atheist—who ascribes to no religion—than they do of a person of any other religion, no matter how different from their own. ]]

Part II, The Evolution of Religion

Ch4, The Roots of Religion

Obviously religions haven’t existed forever; new ones are formed all the time, many short-lived. Recent examples are the cargo-cults on Pacific islands (details p99—John Frumm, and p100). If these religions are false (obviously unlike your own, revealed by God), why don’t they crumble? Even the established major religions have only been around for short times, biologically speaking—or compared to writing, 5000 years old, agriculture, 10,000, language, etc. Why are they created? What purpose do they serve? The traditional answers are that religions

1) provide comfort in matters of life and death

2) explain the universe

3) encourage cooperation against enemies

But why do certain ideas that religions provide satisfy these needs? Why do *these* ideas comfort people?

This and the next four chapters will tell the best current version that science can tell about how religions have become what they are.

The raw materials of where religions come from start with the evolution of the mind; see works by Diamond 1997, Boyer 2001, Atran 2002, Wilson 2002 [involving group selection]. Early minds develop ‘concepts’ about their surroundings, including (p108t) an agent-detector, a memory manager, a cheater detector, a moral intuition generator, a sweet tooth for stories and storytelling, various alarm systems, and what author calls the ‘intentional stance’—the idea that there are *other* minds with their own beliefs and behaviors. These ‘concepts’ lead to religion of some kind, Boyer claims. Thus animals learn to protect themselves from predators, in what has become a never-ending arms race. Humans seems to be the only animals with 2nd and higher order intentionality—imagining what someone else might think or should think, etc. Thus what every person learns as ‘folk psychology’ about how people think.

The habit of regarding how others think is so strong that when someone dies, it’s hard to turn off constantly thinking what the other person would think or feel; that, combined with the necessity of disposing of a corpse, gives rise to elaborate ceremonies (funerals), and the idea of ‘spirits’ left behind – the kernels of religion. How does this involve language? Language further enables dwelling on such topics.

Ch 5, Religion, the Early Days

So projecting an ‘intentional stance’ onto the world gave rise to animism, the idea that everything has a soul, a habit of thought that persists even now in certain words and phrases.

At the same time the human mind, able to consider from among an unlimited range of possible thoughts, but with limited attention to do so, became attracted to certain types of ideas, certain vital combinations that seemed partly plausible and partly fascinating—invisible bananas, trees that walk. (aside about evolution – p120b) These became a sort of fiction-generator. Our memories are episodic, and we rehearse events from our past over and over. We’re attracted by supernormal stimuli—music, which plays off speech (vowels and consonants), art, which exaggerates the colors of the natural world. All this accounts for superstition, broadly, though not religion; we haven’t accounted for belief. (People don’t ‘believe’ in Cinderella.)

Humans are obsessed by strategic information—what other people know that affects their relationships among each other; who knows what and doesn’t know. The plots of all literature hinge on the fact that different people have different sets of information. But what if there were agent who knew everything? Or at least everything worth knowing (strategic info). Just the idea of such an agent helps clarify thinking about what oneself should do next. This suggests why ancestors became objects of worship; after all, babies grow up implicitly trusting adults (just as adults instinctively take care of children).

Not everything is genetic; natural selection can rely on physical laws, and stable environments. One mechanism of transmission is imprinting—a newborn has the instinct to adults, as adults are instinctively drawn to attend to infants—thus the response to the shape of an infant’s face. It’s in the genetic interest of parents to inform, not misinform, their children; thus it’s efficient for children to trust their parents. But leaves open a door to opportunistic memes—example of telling one’s child to *push* their pain into their parent.

Another human issue is how to decide things; divination presumably arose as a means of making decisions, whether or not any good basis was available for making a choice. A flip of a coin is a way of letting chance decide something, just to get on with life. There are dozens of similar means…all the way to numerology and astrology.

Jaynes notes the idea of randomness is fairly recent – earlier, everything was presumed to mean something. [And some people still think this.]

Shamans and rituals are common in all cultures, perhaps because, all the local herbs and means of using them having already been discovered, using them in a ritual enabled repeated discovery of the placebo effects—that patients sometimes got better if they believed they would. There’s a connection to the ability of people to be hypnotized, a function that may lead to the so-called ‘god center’ of Dean Hamer. Thus folk religion.

Another function of rituals is for memory-engineering. Rituals are expensive; why go to all the trouble? Because any lineage needs high-fidelity reproduction of religious traditions to last, or it will quickly become extinct. Rituals seems like they’re memorized and preserved for generations, but evidence actually suggests they’re not—but it doesn’t matter that they’re not. (Interesting aside on projecting backward the evolution of language – p145t) The same way computers and ship chronometers are multiplexed to ensure reliable transmission of data, memes transmit through public repetition, i.e. rituals. But what is the motive to participate in rituals? Note that shamans work in public. The features of these rituals, rhythm and rhyme, the possibilities reduced to a simple set of moves, and a certain amount of rote learning, have the effect of preserving the tradition.

Ch 6, The Evolution of Stewardship

Folk religion became organized religion much as folk music became formalized, with professionals, rules, critics, agents. There are rules behind any performance, and effective religious services resemble musical performances. (For some, ‘explaining’ music or why a service is effective would be to diminish the wonder; but they wouldn’t say that about watching sports.)

Some traditions don’t require stewardship—language, and folk religion. But people are more curious than animals and have a habit, at least some of them, and investigate what people think they already know. (We assume most of what we think we know as a practical matter of ‘faith’ anyway; we can’t each verify every belief about the world –p160m.)

Folk religions are unconscious religions; their practitioners don’t distinguish their ‘beliefs’ from the rest of their lives. (And when queried by anthropologists about their beliefs, are confused and may even invent beliefs on the spot to satisfy the questioner.) The spirits of folk religions don’t exist, it must be admitted.

So what happens when a curious person thinks about what ‘everyone knows’ and discovers something different? Some end up among topics shielded by a ‘systematic invulnerability to disproof’—they are called mysteries that can’t be explained, or topics it is prohibited to question.

Shamans use the technique consciously or not to impress clients; deliberate con artistry explains a lot about some of them, even modern religious leaders. [note film Marjoe, 1972] p.167

Elements of folk religions became selected for various reasons. Religions became organized as the discovery of agriculture permitted large settlements of people, and increased specialization of individuals, and the formation of guilds of specialists. Just as animals were domesticated, so were folk religions, with those doing the choosing often doing so for their own advantage—in what’s been called the kleptocracy of government by thieves—serving the function of justifying the government to the masses. How would religions do this? By creating a bond among groups of people who are not close relatives; and providing a motive for self-sacrifice of individuals for the group, making wars possible. Another means was the idea of being subservient to an invisible god to whom everyone is accountable—and heaping praise on it, just as servants learn to praise their superiors.

[[ the discussion, in effect, is how certain possible elements of folk religions are effective at making them organized work better than others—a sort of natural selection of religious components. Thus all religions have certain features in common [while otherwise making contradictory claims] – e.g. accepting inferior status to an invisible god, as a way of among other things ensuring Machiavellian loyalty. ]]

Author’s summary: [[ The author has handy paragraph summaries at the end of each chapter, immediately followed by paragraph previews of the following chapter. I haven’t relied on these, but before I finish I’ll go through them to see if there are any key ideas I haven’t captured. I wish more nonfiction writers would do this! ]]

The transmission of religion has been attended by voluminous revision, often deliberate and foresighted, as people became stewards of the ideas that had entered them, domesticating them. Secrecy, deception, and systematic invulnerability to disconfirmation are some of the features that have emerged, and these have been designed by processes that were sensitive to new answers to the ‘cui bono?’ question, as the stewards’ motives entered the process.

Ch 7, The Invention of Team Spirit

Any control system must protect itself, or it fails whatever else it is in place for; when a human being can self-reflect, override default presumptions, you can wonder, to whose benefit? The usual answer is the self—self-interest. But it can also be a group, a family or social function.

E.g., a conviction your guild can do good in the world can easily slide to a purpose of maintaining the institute itself, never mind doing good. People steward religions because they believe they are the best way to a moral life, to being good. (This is a separate question from whether religions provide any biological fitness.)

Two hypotheses:

1, Almost all religions promise their adherents that they and they alone are chosen of god and will be saved given proper rituals and prayers. A source of comfort. Such comfort might indeed by a fitness booster.

2, participation in religion advances bonds among groups of individuals to act together more effectively.

Either or both of these may be true. What would they imply about the moral value of religion?

(2)

Why do people join groups? Obvious reasons don’t explain how group formation overcomes difficulties like defection or betrayal. That global cooperation doesn’t exist shows that what cooperative groups we do have are rare achievements.

This might be one function of religion—to overcome suspicion and create group cohesiveness. But how would they get started? Two paths: the anti-colony route and the corporation route. In the first, there are no individual agents making decision; natural selection brought about individuals who cooperated without thinking. In the second, individual humans make rational choices. This question hasn’t been asked, let alone answered, a failure of the functionalist school of sociology, and for that matter of the Gaia hypothesis—how could that have come about?

David Sloan Wilson tried to approach this by applying Darwinian selection to the group level – competition between groups that works at a level different than among individuals. Some group-level processes have been observed among ants—but humans are very different than ants. Wilson thinks competition between religious groups can explain some of their design features.

The other idea is that sacrifice for one’s religious group *is* a cost-benefit behavior just as, say, crime is. [[ A glance at popular news the past few years suggests very obvious ‘competitions’ between different kinds of churches for the social and/or psychological benefits religions provide – you never see shifts in membership of different churches being due to some rational discovery about which faith is true. This is another kind of reality check that explains a lot by implication about the truth of religious faith. ]]

Yet current supply-side market behavior doesn’t explain how religion acquired any structure in the first place. Many religions form and die without notice. Perhaps the few that do are like random mutations…

Perhaps Wilson’s idea applies not to groups but to memes. Wilson assumed religious memes by themselves would be detrimental parasites. But most memes, like viruses, are neutral or even helpful.

Author offers alternative idea:

Memes that foster group solidarity are fit in circumstances in which the host survival depends on joining groups…(p184)… the existence of which help propagate such memes.

This idea avoids insulting religious people who resent the idea they shop around for the best provider. [[ even though many of them do ]] Memes account for this—the initial capture doesn’t have to be rational, in fact it shouldn’t be, it should be acquired by overcoming rational resistance by encouraging passivity or receptivity in the host. Don’t think, do.

This liability for sudden conversion is a curious feature of the mind, even without any religious angle.

Remember that ‘islam’ means ‘submission’. For some Christians, spreading the Word can override even their reproductive instinct. Rational choice theory comes into play in the conscious consideration of the various memes available—by thinking about them before putting anything into action. This can lead to mistakes, just as in genetic engineering.

Note to humanities and social scientists: Thus we have sketched an evolutionary path from nature to the way humans passionately defend their most exalted ideas.

The market of ideas expands with secular institutions as well. Political parties, labor unions, sports teams, the mafia. P188

(3) the growth market in religion

Why do people make sacrifices for religions? There could be both rational and naturalistic responses. Stark and colleagues have concluded that religion can’t be dismissed on grounds of stupidity, neurosis, ignorance, etc. Rather, religion in America is a free marketplace. Evangelical churches provide a superior product. In a later book Stark examine which doctrines have the greatest appeal. [[ well, *obviously*… people aren’t satisfied with a religious concept that isn’t psychologically meaningful, if not comforting, in some way – thus it’s more about a reflection of human needs and desires than anything real ]] The most attractive being the responsive, fatherly God. A counterbalancing Satan. Or there’d be no drama. Which happens to get closer to the truth? That would be convenient.

(4) a god you can talk to

So abstract conceptions of god can’t be asked for anything. You can’t just pray and receive. So how do religions entice customers to wait? People make ‘payments’ all their life. Because the value of the result – results of great value *because* of the great expense. This explains even the cost of ‘high tension’ churches at greater odds with society.

The more you invest, the more you protect that investment. Group solidarity results in xenophobia, a price many are willing to pay.

These ideas explain that religious firms exploit social conflict as a way of generating business. [[ this suggests that social conflict precedes religious affiliation..? the frightened conservatives gather together to support each other? ]] This makes it dangerous for churches to attempt reforms; reforms can disillusion followers.

Author presents all these as ideas which need further research.

Would there be any future in a Godless religion? There are examples of such religions, generally small elite groups. Why persist at all?

(Pause here).

\\

“Bright” was a term introduced by the Brights Movement to characterize rationalists and atheists, and accepted by Dennett for a while, though disapproved of by Mooney, Hitchens, and others. This Wikipedia article quotes Dennett:

There was also a negative response, largely objecting to the term that had been chosen [not by me]: bright, which seemed to imply that others were dim or stupid. But the term, modeled on the highly successful hijacking of the ordinary word “gay” by homosexuals, does not have to have that implication. Those who are not gays are not necessarily glum; they’re straight. Those who are not brights are not necessarily dim.