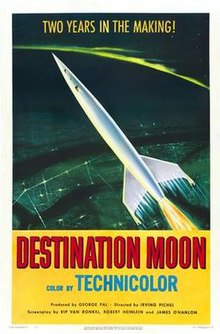

This 1951 film was the first prestigious science fiction film, its script inspired or perhaps partially written, by Robert A. Heinlein. The credits say “from a novel by” Heinlein but that’s not accurate. Heinlein had written a juvenile novel about a rocket to the moon, Rocketship Galileo, and he’d written a novella, “The Man Who Sold the Moon,” concerning a single rich inventor who builds a rocket to the moon all by himself… but neither of those correspond to the plot of this movie. (Heinlein did, however, write a prose version of this movie’s script, published in one of the science fiction magazines several months after the movie premiered.)

It’s a George Pal production, though directed by Irving Pichel; Pal later did When Worlds Collide, the 1953 The War of the Worlds, and the 1960 The Time Machine among others. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Pal. He was arguably the greatest director of science fiction films in the 1950s and 1960s.

This film stands in contrast with Rocketship X-M (http://www.markrkelly.com/Blog/2020/07/23/skiffy-flix-rocketship-x-m/), a cheaper film released a month earlier; this one is much more scientifically accurate, if nevertheless a tad less melodramatic.

Gist

The first rocket to the Moon is hastily launched in the face of legal challenges and public fears. A repair en route requires spacewalks, during which one of the men becomes untethered and is rescued. They land on the moon but use too much fuel doing so, and to return to Earth have to lighten their weight by jettisoning non-essential parts from the rocket’s interior.

Take

This is a sober, mostly scientifically-accurate depiction of how the best 1950-era writers and filmmakers imagined how the first rocket to the moon would happen.

Summary

- Opening scenes show a desert military base, where a V-2-like rocket, with black and white fins, is launched–and quickly crashes into the ground. Watchers inside wonder, what went wrong? Could it be sabotage?

- Later at plane factory, a General Thayer arrives to talk with Jim Barnes, head of the corporation. Acknowledging the failure of Cargraves’ rocket, Thayer appeals for Barnes’ help; Barnes is reluctant, he’s just a manufacturer. Thayer says the matter is bigger: the next rocket will go to the moon, with a new atomic energy engine. Soon there’s a presentation to a roomful of entrepreneurs. The themes in these scenes are two: only industry can do the job, not the government, and it’s urgent to establish a base on the moon to prevent other countries from doing so, and launching missiles from the moon.

- A highlight of these scenes is a five-minute Woody Woodpecker cartoon showing how rockets work: how they launch, how they reach escape velocity, how they keep “falling.”

- The story proceeds straightforwardly. We see a montage of draftsmen and engineers working. We see the ship under construction. The decision to launch is pushed up, as a commission denies their request, and public opinion about the risk of an atomic explosion.. At the last minute one of the crew of four has a “bellyache” and so radio operator Joe, with a broad (New York? New Jersey?) accent, and skeptical that the rocket will even take off, is substituted. (The others in the crew aren’t trained astronauts; they’re the main characters we’ve already met! The general, the manufacturer, the rocket designer.)

- The ship launches. They discover their antenna is locked in place and need to make an excursion outside to fix it. All four of them end up outside, as one at the far end of the ship, his anchor line not long enough, comes loose from the hull despite his magnetic boots. He hangs out in space until rescue can be arranged. (Much as in the first two episodes of Lost in Space.)

- Soon they land on the moon, the rocket descending onto its tail, but — much like the real Apollo 11 in 1969 — the pilot overshoots their target and uses too much fuel before setting down.

- Emerging onto the moon, Cargraves speaks: “By the grace of God, and in the name of the United States of America, I take possession of this planet on behalf of and for the benefit of all mankind.” Thus accomplishing a primary goal of the mission. Subsequent scenes show the four men breaking out equipment, large cameras, a Geiger counter, to do some rudimentary exploration.

- The whole final quarter or third of the film, though, is dominated by the problem of launching back toward Earth. Their landing used so much fuel, they don’t have enough for their planned launch. So they need to strip the rocket of every possible nonessential part–the acceleration couches, half the ladder, some control panels, all the exploration equipment. it’s still not enough. Does on of them stay behind? They debate it, each offering to be the one. Joe escapes the ship to be the sacrifice, but at the last moment Barnes gets an idea that involves dumping all four spacesuits, the last one pulled out of the ship by the weight of an oxygen tank on a tether.

- And so they launch off the moon, and see the Earth ahead. The end. Or actually, as the credits read, “The End… of the beginning.”

Comments

- The theme here of private enterprise building a rocket to the moon is reflected in Heinlein’s two prose stories on the first rocket to the Moon: the novel Rocket Ship Galileo, and the novella “The Man Who Sold the Moon.”

- The technical advisor, listed in the opening credits, is (famous astronomical artist) Chesley Bonestell. And indeed, the moon’s surface is depicted here with high craggy mountains, as astronomical art of the time commonly showed.

- There’s a modicum of futuristic set design in Dr. Barnes’ office, with sliding metal doors for the entrance and to the restroom.

- As in most books and films from this era, everyone smokes, especially cigars.

- In general the film is highly accurate scientifically, especially compared to its contemporary Rocketship X-M, but there are a couple scenes that aren’t quite right.

- First, as did some other movies from this era, it presumes that magnetic boots would be needed to anchor oneself to the floor, or to the outside of the ship, in the absence of gravity or acceleration. For that matter, so did 2001, in 1968, except by then they were Velcro slippers rather than big clunky boots. It didn’t occur to anyone that there really wouldn’t be any problem just floating around, inside the ship, or even outside once secure by line or with maneuvering jets.

- The exterior space walk scene is OK up to a point; once the one astronaut gets loose, though, he just sorta hangs out there a few dozen feet from the rocket without actually moving farther away, as he would once he began moving away from the ship at all. (Some issue in those Lost in Space scenes.)

- For that matter, as Heinlein’s other stories did (but Rocketship X-M did not), it depicts a large single-staged rocket launching from Earth, landing on the moon, and returning—no multiple stages that dropped away when no longer needed, no separate lunar lander. (Clarke more correctly anticipated staged launches in his novel Prelude to Space.)

- Both this film, and Rocketship X-M, have jokes about Texas and harmonicas.

- The last-minute addition of the radio jock Joe to the crew serves two purposes: he provides some broad comic relief, especially with that accent (“the ship won’t woik!”) and he serves a narrative purpose giving reason for the three professionals aboard to explain things (to the audience), e.g., why exiting the rocket in a spaceship won’t result in falling away or being swept away.

- The film’s trailer, shown after the movie proper, indicates that there was much publicity for this film in all the major magazines of the day.