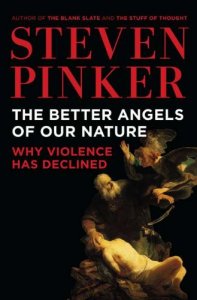

More on Steven Pinker’s magisterial 2011 book, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined — one of the best books of the 21st century, surely — that takes a long-range view of human history to show that the human condition, over millennia and especially in recent centuries and decades, has vastly improved in terms of the reduced likelihood of any person dying of violence, and thus the betterment of the human condition.

More on Steven Pinker’s magisterial 2011 book, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined — one of the best books of the 21st century, surely — that takes a long-range view of human history to show that the human condition, over millennia and especially in recent centuries and decades, has vastly improved in terms of the reduced likelihood of any person dying of violence, and thus the betterment of the human condition.

(Earlier posts on this book here and here)

A bit more on Chapter 1: A Foreign Country

- The medieval knights – like those in Camelot – were set in the 6th century, via stories written in the 11th to 13th The stories recount extreme violence every few pages – skulls split, decapitations, etc. etc. Lancelot was regarded as a ‘gentleman’ for never killing a knight who begged for mercy.

- The realm of early modern Europe, its kings and queens, includes beheaded queens and other murders among family members, as recounted in Shakespeare. Grimm’s fairy tales include at least three stepmothers who attempt to murder their children. Punch and Judy were a famous puppet act, featuring infanticide and murder. Even Mother Goose, in the 17th and 18th centuries, features traumatic violence of a sort that wouldn’t be tolerated today.

- ‘Honor’ later involved duels, as that of Alexander Hamilton, who died in one. Dueling is an example of a behavior that persisted for centuries, before abruptly vanishing, and subject to ridicule, p23t.

- In the 20th century we’ve seen a decline in martial culture – e.g. the flaunting of public works of military men, the naming of subway stops for military battles, etc. In contrast, modern memorials to wars more often list names of the victims.

- Even nuclear weapons were glamorized in the 1950s, via names like ‘bikini’ and the design of toys and cafes. Everyday force was common – men engaging in fistfights; Truman threatening a critic with a black eye; Charles Atlas ads. [[ and Star Trek!! In the 1960s, patterned after TV Westerns of the time, with stories that routinely included fistfights, a feature IIRC absent from TNG just two decades later. ]]

- 1950s TV featured spousal abuse; ads implied it; a song in (the very famous stage musical) The Fantasticks was all about rape.

- Children were spanked, now rare.

- P28-29, author imagines a speech given in 1976 that promised a peaceful future – in which he would likely not be believed.

TL;DR summary of detailed notes below:

Chapter 2: Pinker describes the “Pacification Process,” in which the violence that arose in the human species (comparing how violence is carried out by chimps) was mostly deployed for strategic reasons: competition with other tribes; as a means of discouraging attack by others; and to promote individual and tribal glory, which is a means of demonstrating ‘credibility,’ i.e. the promise of effective response to attacks.

Hobbes’ solution was the “Leviathan,” the idea of a government of some sort that has a monopoly on the use of force. And this is more or less what happened, the Leviathan brought about by the historical forces of growing population and the agriculture revolution.

Chapter 3: And then, the “Civilizing Process”: Evidence shows violence in cities is lower than in rural areas, that the trend toward urbanization and cosmopolitan life encouraged decreased violence. Pinker describes medieval life, etiquette manuals, how primitive cultures of honor gave way to culture of dignity, from the 11th to 18th centuries, as people adopted greater self-control and empathy and in order to live together and larger and larger groups.

There have been aberrations, like World War II. And violence is still more common among lower classes (who feel themselves out of touch with the local ‘Leviathan’ or government) and in remote areas or the world.

And then Pinker explores why violence increased in the 1960s, and then decreased again the 1990s, with some startling insights into the red vs. blue state divide in the US, and why the apparently coarse culture in contemporary US is a sign of progress, not social decay.

\\

Detailed notes with quotes:

Chapter 2, The Pacification Process

- Hobbes and Darwin both provided insights into the origins of violence.

- Darwin’s theory has (since his day) been extended with genetics and game theory, e.g. Dawkins characterization of animals as ‘survival machines.’ His analysis indicates however bloody animals may attack each other, it’s for strategic reasons, p33t – only when it would benefit them.

- Hobbes, in contrast, supposed that it was inherent in man to quarrel, for three reasons: competition; diffidence [i.e. fear of being attacked]; and glory. We understand today why wives would be subject to competition, because of different investments of men v women. The idea of glory, or honor, is best thought of as ‘credibility’ p34.8. The security trap is solved via deterrence, e.g. MAD during the Cold War. We also understand now how “a major design feature in human nature, self-serving biases, can make each side believe that its own violence was an act of justified retaliation while the other’s was an act of unprovoked aggression.” P34b. (later, p46.5 characterizes these three reasons as gain, safety, and credible deterrence.)

- But Hobbes wrote of anarchy; his solution was ‘Leviathan,’ a government of some sort that has a monopoly on the use of force. Law is better than war; see diagram 35b.

- In contrast to Hobbes was Rousseau who thought primitive savages innocent and gentle.

- The debate between the two viewpoints became political in the 20th century, with liberal ideals preferring Rousseau. But neither had any evidence. We can do better, by examining rates of violence in societies that live under a Leviathan, and those that live in anarchy.

- P36, Violence in human ancestors

- We can start by examining chimps, with whom we share a common ancestor. Jane Goodall observed how gangs of chimps attack each other, especially isolated males; kill others’ offsprings, and so on p37-40

- Our own species is about 200,000 yrs old, behaviorally modern for 75,000 yrs, and only for the past 10,000 yrs has lived in “stratified societies numbering in the millions, eat foods cultivated by agriculture, and are governed by states” p40b. But that 10K boundary marks only the earliest societies that farmed; some areas took much longer. Nor are societies only hunter-gatherer, or agricultural; many are a blend. True states didn’t appear until 5,000 years later.

- It was long thought that nonstate societies were ferocious barbarians. Evidence shows same kinds of raids and battles that chimps engage in; plenty tales of savagery, to p56, even cannibalism. Three reasons; most commonly for vengeance, as deterrence against other attacks.

- Rates of violence: it’s important to discuss how rates of violence in a population are significant, not absolute numbers. Then follow several pages of charts and discussion, e.g. p49, showing very high rates among prehistoric sites, and contemporary hunter-gathers, and very low ones in modern centuries.

- P56, so was Hobbes right? In part. Even in such states, life is peaceful most of the time.

- Why did our ancestors leave Eden? 57m. It might not have been a choice: growing population required agriculture, even if early settlements (as in the Bible) involved “totalistic ideologies and brutal punishments” p57.8

- And complex societies are more likely toward other problems… p58.3: “People were less likely to become victims of homicide or casualties of war, but they were now under the thumbs of tyrants, clerics, and kleptocrats…”

Ch3, The Civilizing Process

- Author tells anecdote about growing up, and how he never understood the rule about not using one’s knife to scoop peas onto one’s fork.

- Now he understands, due to the work of Norbert Elias, who published a book in 1939 called The Civilizing Process (from which chapter title is taken).

- Later, in 1981, someone plotted historical rates of homicide in Europe, from 1200 to 2000 – figure on p60 – showing great declines, by close to a factor of 100. Despite stereotypes about the idyllic past…

- Further data confirms the trend, and in other European regions. It seems that urbanization made life safe – not more dangerous! Quote p64b:

- “Is it your conviction that small-town life, centered on church, tradition, and fear of God, is our best bulwark against murder and mayhem? Well, think again. As Europe became more urban, cosmopolitan, commercial, industrialized, and secular, it got safer and safer.”

- Back to Elias—he started by analyzing 15th-century drawings of medieval life (p65,66)—showing various depravities and acts of violence, as seen through the eyes of a knight.

- Knights of that time were what we would today call warlords. Quotes from Barbara Tuchman (from her popular book on the 14th century), with examples of violent games and the routine idea of cutting noses off.

- Tuchman and others note how the temperament of medieval people was childlike, impulsive, uninhibited.

- Elias also examine etiquette manuals, e.g. long lists of rules about bathroom issues, manners at the dinner table, and so on –p69ff – issues we expect 3-year-olds to understand today; but these were written for adults!

- They were all about: control your appetites; delay gratification; consider the sensibilities of others; don’t act like a peasant; distance yourself from your animal nature. (p71t)

- They were about shame—not hygiene, which wasn’t then understood in modern terms.

- There are remnants of these changes in the language; there were rules about using knives, not displaying them too casually; even taboos about their use—including a rule about pushing food around. Aha! P72.5

- So Elias’ theory is that, over a span of centuries from the 11th to the 18th, a culture of honor gave way to a culture of dignity; people became socialized at younger ages. Two trends: self-control; and empathy.

- Critics of Elias note that all societies have ‘standards of propriety’… and Elias conceded that there “is no zero point”, i.e. there was no baseline with no standards at all.

- Elias proposed two ‘triggers’ for this change. First, the consolidation of a genuine ‘Leviathan’, i.e. centralized monarchies after centuries of feudal baronies and fiefs. Monarchs discouraged fighting among the knights, because they caused losses. Homicide became a state matter. Fealty to monarchies entailed courtly manners; courtesy. Thus those etiquette guides. And the military revolution, with the invention of gunpower, and the necessity of state to support expensive technologies.

- Second, economic revolution, hobbled by Christian resistance to commerce, that money was evil etc., p75b. Thus the Jews become the moneylenders! And business developed positive-sum games; the trading of surpluses; keying off evolutionary psychological insights about sympathy, trust, gratitude, guilt, anger, p76m.

- Thereby came divisions of labor; a network of transportation; and idea of money, to replace barter. [[ need to compare Harari, whose notion is that money was one of the key ideologies (he even calls them religions – i.e. an agreed-upon shared belief that something that didn’t physically exist, nevertheless existed ]]. All of this summarized as ‘gentle commerce.’

- In a sense both of these – Leviathan, and gentle commerce – were part of a single organic process; and here Pinker explicitly cites Robert Wright’s Nonzero, p78.6

- Elias’ theory made a prediction that turned out to be true: that rates of violence did drop, over that period.

- So what about World War II? Well, that was different; it wasn’t a retreat to feudalism or anything of the sort.

- Pinker acknowledge libertarian skeptics who point out how norms of cooperation develop anyway, e.g. with example of the sailors in Moby-Dick. Author points out that even these live with the ‘shadow’ of Leviathan – another example of ranchers in northern California. Minor disputes would be solved by their culture of honor; yet serious disputes would accede to governmental oversight.

- There are two rule-proving exceptions to this trend of decreasing violence over history: lower classes, and isolated areas of the world.

- Violence was once common among aristocrats (e.g. Romeo & Juliet opening) but is now virtually zero. Violence still persists among lower classes, but mostly as a pursuit of justice, as a reaction against insults, unfaithful partners, etc., feeling themselves stateless out of reach of legitimate government.

- Second, the civilizing process began in western Europe and spread outward; mountainous regions, e.g. Scotland and Ireland, remained violent longer. We don’t have comprehensive data about trends in much of the world; WHO data p88. But recall anecdotes about how the Chinese don’t allow knives at the dinner table at all – food is cut into bite sized pieces in the kitchen (of course!) – suggesting a similar pattern of increased etiquette that paralleled a gradual decline of violence.

- And violence rises in former colonies as they go independent (and government oversight loosens or withdraws).

- P91What about the US? Why is violence in the US so high compared to Europe? It’s not just the effect of having more guns; US is more violent even when the effects of gun are taken away (i.e. violence due to knives, etc. etc.)

- The answer is that the US is really three counties. Violence is higher in southern states, in part due to the legacy of the civil war, and the origin of immigrants – many Scots and Irish settled the South. Violence is higher among blacks, because they are more likely lower class.

- In a sense democracy came too early to the US, with its 2nd amendment established before civilizing effects had taken place. Thus the South developed a culture of honor—promises of personal retribution for disputes, rather than an appeal to law. Recall Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, the Hatfields and the McCoys. Southern states give a person wide latitude to kill in defense of property, have fewer gun restrictions, etc., 99b. Yet is there an exogenous cause? Again, the Scots and Irish were herders, and herders around the world depend on this kind of culture of honor to protect their assets.

- Then there’s the American West, p102, with its cowboys, miners, and so on. Here the reason was the preponderance of men, who with the alternatives of beings ‘cads’ vs. ‘dads’, more often acted the former. The west was tamed by the eventual influx of women, and temperance movements to restrain alcohol. The marriage effect is well-known among sociologists as a civilizing effect on men. P106

- Here Pinker summarizes with a cogent conclusion of these trends to explain the current blue vs. red state divide in the US:

- “An appreciation of the Civilizing Process in the American West and rural South helps to make sense of the American political landscape today. Many northern and coastal intellectuals are puzzled by the culture of their red state compatriots, with their embrace of guns, capital punishment, small government, evangelical Christianity, “family values,” and sexual propriety. Their opposite numbers are just as baffled by the blue staters’ timidity toward criminals and foreign enemies, their trust in government, their intellectualized secularism, and their tolerance of licentiousness. This so-called culture war, I suspect, is the product of a history in which white America took two different paths to civilization. The North is an extension of Europe and continued the court- and commerce-driven Civilizing Process that had been gathering momentum since the Middle Ages. The South and West preserved the culture of honor that sprang up in the anarchic parts of the growing country, balanced by their own civilizing forces of churches, families, and temperance.”

- Then what happened in the 1960s? Both the US and Europe, rates of violence went up; murder rates per 100,000 from 4 in 1957 to 10.2 in 1980, and 72 among blacks. The trend was depicted in popular culture, with TV and movies focused on urban violence. Conservatives won elections by being “tough on crime.”

- Various solutions have been proposed. Partly it was an effect of baby boomers, a growth in the population of young people, especially in proportion to older people. Also their connection in an age of TV (when everyone watched the same three networks) and the transistor radio, a shared culture brought about a feeling of solidarity among that generation. And increased democracy brought about an ‘informalizing process’ 109b, affecting dress and manners.

- Also, the ‘establishment’ became blotted with moral stains: the threat of nuclear war, poverty, mistreatment of native Americans, the Vietnam war, the oppression of women and homosexuals.

- These currents pushed back against elements of the ‘civilizing tide’—self-control relaxed, so that “if it feels good, do it”; and the idea of interdependency eroded, thus the “rolling stone”, and “tune in, turn on, drop out” and many similar notions in song lyrics and movie scenes.

- Along with these, reaction against the ideal of marriage and family life, which became Ozzie and Harriet corny. Hippies flaunted standards of cleanliness and continence. They threw away their watches; no one cared what time it was. Rock musicians smashed guitars on stage, events that at times spilled over into interpersonal violence.

- So: were the reactionaries who vilified rock music right?

- Not exactly. There were other trends. Criminal justice relaxed, and elites found Marxism fashionable to the point of excusing some kinds of violent protest. Law enforcement retreated; people abandoned city centers for the suburbs. And the sexual revolution left young men without the responsibilities of marriage and family.

- And then in the 1990s the trend in violence reversed, returning to 1950s level, and even below. No one predicted it, and still there is no simple explanation.

- One idea, promoted by the authors of Freakonomics, was that availability of abortions in the ‘70s led to the non-births of unwanted children, who otherwise might have grown up lawless. But studies, and actual data, don’t support the theory. (E.g. the women who do have abortions are more likely to plan for the future; those who don’t are more likely to have children who don’t and who are the irresponsible ones more likely to commit violence.)

- Rather, there were two areas of causes. First, ‘Leviathan’ became more effective; second, the civilizing process was restored.

- First: incarceration rates increased, perhaps more than it should have, but this removed from the general population those most likely to commit violence. (Canada didn’t, and their violence rate declined too, so this is only part of the explanation.)

- And police forces expanded, aligned with the popular ‘broken windows’ theory that encourages good behavior if minor problems around neighborhoods are addressed. Experiments support it. [[ This recalls such mental biases as the anchoring effect, and priming. ]]

- Second, norms changed. Some of the radical ideas of the ‘60s lost their appeal. Civil rights movements made law and order a progressive movement, not just a reactionary one.

- And some communities organized women and church groups to break up gangs and encourage good behavior, e.g. in Boston.

- And a change in punishment strategy made it not so random and more predictable, in ways that appeal to our psychology, 126.7.

- And there were prominent rallies, the Million Man March and Promise Keepers, which may have had positive effects despite their “unsavory streaks of ethnocentrism, sexism, and religious fundamentalism…”

- Pop culture, it’s notable, is still decadent – violence in movies, in video games, pornography, is as common as ever. The difference is now people treat it ironically, post-modernly. People indulge in counter-culture looks without adopting unconventional lifestyles.

- This might be a sort of ‘third nature’, following the first two; we consciously reflect on cultural norms to decide which are worth adhering to, and which have outlived their usefulness. Further, we can *afford* to indulge in ‘decadent’ behavior – swearing, very casual dress – because those things are no longer true indicators of cultural decay.

This last point is startling. It’s commonly thought that contemporary culture is coarse and degraded, in that profanity is more commonplace (even in staid print publications) and fashion is sloppy and lascivious, compared to say the 1950s. Pinker suggests how the opposite is true; I’ll quote in detail, from p128:

If our first nature consists of the evolved motives that govern life in a state of nature, and our second nature consists of the ingrained habits of a civilized society, then our third nature consists of a conscious reflection on these habits, in which we evaluate which aspects of a culture’s norms are worth adhering to and which have outlived their usefulness. Centuries ago our ancestors may have had to squelch all signs of spontaneity and individuality in order to civilize themselves, but now that norms of nonviolence are entrenched, we can let up on particular inhibitions that may be obsolete. In this way of thinking, the fact that women show a lot of skin or that men curse in public is not a sign of cultural decay. On the contrary, it’s a sign that they live in a society that is so civilized that they don’t have to fear being harassed or assaulted in response. As the novelist Robert Howard put it, “Civilized men are more discourteous than savages because they know they can be impolite without having their skulls split.” [And, recalling the anecdote at the beginning the chapter, Pinker concludes] Maybe the time has come when I can use a knife to push peas onto my fork.

(And yes, he’s quoting Conan author Robert E. Howard – see https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Robert_E._Howard.)