Clifford D. Simak’s CITY, published in 1952 but composed of stories published in magazines from 1944 onward, is a story cycle that tells the future of humanity as it abandons cities for country estates and then moves off Earth to settle other planets, and in parallel the rise of an artificially created Dog civilization. The individual stories are prefaced by the latter, that is, tales of an ancient past from the point of view of the Dogs, telling stories about ‘Man,’ whom they think are mythical. It’s a well-known, enduring work, having won one of the very earliest awards for SF or fantasy, the International Fantasy Award, in 1953 (http://www.sfadb.com/International_Fantasy_Awards_1953). It’s Simak’s most popular book along with his WAY STATION, published a decade later.

Clifford D. Simak’s CITY, published in 1952 but composed of stories published in magazines from 1944 onward, is a story cycle that tells the future of humanity as it abandons cities for country estates and then moves off Earth to settle other planets, and in parallel the rise of an artificially created Dog civilization. The individual stories are prefaced by the latter, that is, tales of an ancient past from the point of view of the Dogs, telling stories about ‘Man,’ whom they think are mythical. It’s a well-known, enduring work, having won one of the very earliest awards for SF or fantasy, the International Fantasy Award, in 1953 (http://www.sfadb.com/International_Fantasy_Awards_1953). It’s Simak’s most popular book along with his WAY STATION, published a decade later.

(It’s also listed in the recent 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die: A Life-Changing List, by former A Common Reader co-founder James Mustich, which I’ve just compiled this week at sfadb.com: http://www.sfadb.com/1000_Books.)

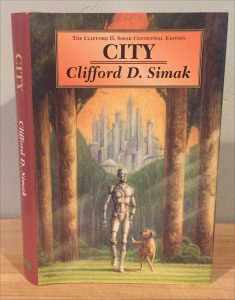

The book consists of eight stories plus an (later-written) epilogue. The edition I’m reading, with pages references below, is the very handsome Old Earth Books edition of 2004. (http://www.oldearthbooks.com/).

The first story, “City,” is set about 50 years in the future of Simak’s writing in 1944 or so, and it projects the development of several technologies – helicopters, planes, hydroponics, atomics – into a future in which cars are obsolete, cities are unnecessary “huddling places”, and most people have chosen to live out in the country (since transportation is so easy and economical). The story concerns the problem of unoccupied houses in the unnamed city where John J. Webster lives, and what to do with them.

Subsequent stories follow succeeding members of the Webster family. The second, “Huddling Place,” concerns Jerome A. Webster living comfortably on the Webster family estate surrounded by benevolent robot servants, as his son Thomas is about to head for Mars. Jerome is uncomfortable leaving home even to see him off. When an urgent request comes for Jerome to journey to Mars himself, to treat Juwain, a Martian philosopher he once knew, he can’t bring himself to do it, having understood the condition of agoraphobia that has settled into the human instinct.

In the third story, “Census,” a World Committee has formed, planets in other star systems are being settled, and there is a hidden population of ‘ridge runners’ who have chosen to live in the hills unaccounted for – extraordinary people who in the past were successful artists, politicians, or crooks. An enumerator, Richard Grant, visits the Websters in search of them, and meets their talking dog Nathaniel; the Websters have pursued the options of advancing dogs into a sentient species. Grant tracks rumors of a mysterious stranger in the woods, Joe, who has created an advanced ant civilization. Grant reveals he is searching for someone to finish a thesis by that Martian philosopher Juwain, one that might change mankind—and the dogs. But Joe, reading a fragment, sees an error and will not reveal it. He’s not interested.

The single most striking story is “Desertion,” set on Jupiter, in which men are transformed into a creature able to survive on its surface and sent out to explore. (The plan is, p98b, “Man would take over Jupiter as he already had taken over the other smaller planets,” an expression of the manifest destiny common in 1940s and ‘50s SF.) A sixth man, Fowler, prepares for his expedition, knowing that the previous five never returned, and no one knows why, and this man takes his dog Towser. They are both transformed and sent out, and both overwhelmed by the experience, perceiving and understanding more than they ever could before; The man realizes they’re now using their brains fully; “Maybe the brains of Earth things naturally are slow and foggy. Maybe we are the morons of the universe…” 107.7 And 108t: “perhaps because we were human beings… Poorly equipped for thinking, poorly equipped in certain senses that one has to have to know. Perhaps even lacking in certain senses that are necessary to true knowledge.” And they realize, they can’t go back. –Spoiler!—because, as expressed in the last lines,

“I can’t go back,” said Towser.

“Nor I,” said Fowler.

“They would turn be back into a dog,” said Towser.

“And me,” said Fowler, “back into a man.”

The next story, “Paradise,” was first published two years after the three prior stories, as if Simak thought a while before deciding to continue. It picks up where the last one left off. Fowler decides to return, to explain. The news reaches Earth, where Fowler meets the latest Webster, who worries that the news that Jupiter is a paradise could spell the end of humanity as it’s been, subverting its “destiny”. Joe is still around, revealing that he and the other mutants have stolen Juwain’s philosophy—which has to do with sensing the viewpoints of others, achieving complete understanding, a kind of ‘semantics’. The mutants don’t need it – they have telepathy – but humans do.

In “Hobbies” Jon Webster exists in a world in which almost all humans have left Earth, and those left behind are too rich, and have nothing to do except pursue hobbies, like painting or creating elaborate cocktails, or writing the book he is writing. He returns to the family estate, where he learns about the “cobblies,” perhaps other dimensions or planes of access, that the dogs have learned about. The dogs are building a brotherhood of animals, “in a direction that man passed by without a second glance.” Webster realizes mankind has wasted its time, and returns to Geneva, where the last 5000 humans on Earth live, and seals it off from the outside world – giving the dogs their chance.

In “Aesop” a dog civilization has come into being, having all but forgotten humans, thinking of them as ‘websters’ in lower case. They live by the Canons, which prohibit any destruction of life; animals don’t eat each other, they eat from feeding stations manned by mutant humans or robots. Jenkins, the head robot, is now 7000 years old. The dogs and robots decide the past doesn’t exist; each moment is a new world in a series of parallel realities. But they now face a world of overpopulation, since the animals don’t eat each other. The solution is the parallel worlds the mutants have accessed.

The final story, “The Simple Way,” brings Jenkins and Jon Webster together again, to solve the destiny of the ants, to whom the world is left.

An “Epilog,” written years later in 1973 (and so not in early editions of the book), tells of Jenkins on a world of mice and ants, as he discovers the ants are dead. A spaceship lands, with Andrew, a wild robot, who tells of other worlds: “There are worlds out there, and life on some of them. Even some intelligence. There is work to do.” And invites Jenkins to join them.

\\

There are lots of brilliant ideas here, and startling developments, but at the same time it’s a kitchen-sink novel in which each story develops a new concept, often to solve the problem set up by the previous story. When I finished it, I wrote, It’s a vague mélange of sentimental themes not thought through, especially by current knowledge. Perhaps this is unfair. That Simak could take an initial premise, about the transformation of human civilization by technology, and extend it, again and again, with notions of bootlegging the intelligence of dogs (and ants) and speculations about how the world is must vaster than the tiny portion humans have perceived, and how humanity might well give way to other species, is an impressive achievement.

But I’ll made these specific points:

- The most striking aspect of the book – in the “Notes” to each tale, added in the book publication – is the retrospective introductions to the stories by the latter dog scholars, who don’t quite believe that humans actually existed. They are a myth. They describe the setting and context for these myths about the strange creatures and their strange concepts. Like ‘city.’

- The first story especially reveals an antipathy toward technology that recalls Ray Bradbury, in its character’s irritation with an automated lawn-mower.

- Simak makes an intelligent insight: that as humanity has dispersed from cities, the threat of nuclear war is reduced (since there are no more centralized targets).

- There’s an aside in the first story about a “Bureau of Human Adjustment” in which it’s revealed that humans are being ‘adjusted,’ mostly covertly, to new ways of life now that the old jobs have disappeared, see p26. This has a modern ring to it [Harari]! And presumably it explains the agoraphobia revealed in the second story.

- It’s amusing how the Dogs (in the latter-day introductions) assume the robots were invented by them, since the robots’ functions are so ideal – they serve has the Dogs’ hands! This is a clever insight, mocking the way human creationists assume the universe exists for their own sake. (The Dogs also dismiss the notion of traveling off the planet as fantasy, since “everyone knows” that stars are just lights hanging in the sky. p40b)

- “Huddling Place” emphasizes the idea of country living, away from the cities: “a manorial existence, based on old family homes and leisurely acres, with atomics supplying power and robots in place of serfs.” And with devices [like VR] to transport one’s image and presence anywhere, in order to transact business anywhere in the world, with the twist of a dial, p45.

- Yes, the stories assume the existence of an intelligent Martian race – as did other books of the era, by Heinlein, Clarke, Silverberg, et al.

- The first couple stories are highly parochial; what’s happening in the rest of the world? Is *everyone* living on lavish family estates with robot servants? Everybody? The unexamined assumption here is that most people would prefer living on country estates, not in cities. But I suspect this merely reveals the author’s personal bias. Simak grew up in rural Wisconsin, where many of his stories are set, and though he lived most of his life as a newspaper man in Minneapolis, he apparently missed his childhood environment, and presumed that most other people would be attracted to it as well.

- The third story “Census,” in which it’s revealed that the Webster family has pursued the option of advancing dogs, through surgery, has a Lamarckian element to it, but anyway it’s an “uplift” event, in the term later popularized by David Brin.

- “Desertion” has a couple crucial themes. First, that perception outside the narrow range of human existence might be extraordinary, full of experiences humans can literally not imagine (however close SF writers like to try). [EO Wilson has emphasized this theme.] OTOH the idea on p107 is off the mark; humans minds are optimized for their environment. More to the point, p108, about ‘true knowledge.’

- In “Paradise” there’s a reference to semantics, and I know that something called “General Semantics” was something of a craze in the 1950s, but I don’t know enough about it to think if Simak was alluding to that.

- Again in “Hobbies” we have the idea of a vaguely mystical theme about some higher truth that mere men cannot access.’

- Here’s a key thought from late in the book: the ants have been successful because they are *stable* in their environment. Humanity, at least in the past 10,000 years, is notably *un*stable – especially in the past few decades and centuries, as humanity is changing the planet’s environment — and that may be why we are doomed.