This was Clarke’s first novel after “returning” to writing novels after the break of nearly a decade collaborating with Stanley Kubrick on the book and film 2001: A Space Odyssey. (His previous major novel had been A Fall of Moondust in 1961.) In the fact success of 2001 facilitated a major 3-book for a record sum of money; Rama was the first, and was followed by Imperial Earth in 1975 and The Fountains of Paradise in 1979. And these three were his last substantial novels, followed only by 2001 sequels and three relatively short novels in the late ‘80s and early ’90.

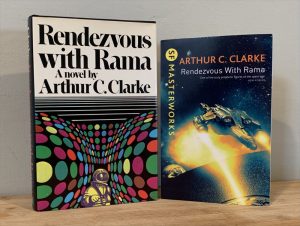

The book was significant for me in that it was one of the first hardcover SF novels I bought, back then in 1973, along with, the same year, Heinlein’s Time Enough for Love. My Harcourt Brace Jovanovich edition is the first US edition; the earlier actual first edition, from British published Gollancz, came out a couple months earlier. Also in the photo is the current trade paperback edition, from Gollancz in 2006.

The novel’s plot is simple: an alien spacecraft, at first thought to be an asteroid, enters the solar system from interstellar space, headed for a close pass around the sun. It’s named Rama. An International Space Advisory Council sends a ship, the Endeavour, to intercept it. Rama is huge, cylindrical, alien, and uninhabited. The IAC ship’s crewmen board and enter it, explore for a while, and then withdraw as they realize Rama isn’t settling into any kind of local orbit, but is using the sun to escape the solar system and head back out into space.

“That’s it.” I recall one of the news magazines (Time or Newsweek?) of the day publishing a review, obviously written by someone unsympathetic to science fiction, that ends its precis with those words, as if the reviewer had found nothing in the book he felt necessary for a “novel.” But then virtually all reviews and essays about science fiction in mainstream publications of that era were similarly dismissive.

In fact, Rama was and remains a significant and popular novel. It’s of a class of SF works about so-called “big dumb objects,” enormous alien artifacts that are explored by humans, to some success or not. (The famous progenitor to Rama was Larry Niven’s Ringworld in 1970.)

So the interest here is in Clarke imagining how alien technology might work, what it might be for, and how human explorers might try to understand it. It’s a book as much about all its incidental detail as about any broad crisis and resolution. (There is one crisis subplot, about a threat by the human colony on Mercury to destroy it.) And in fact, the purpose and functioning of Rama remain unknown as the book ends.

The bulk of the novel is about the human astronauts entering the inside of Rama, a huge cylinder that spins so that “artificial gravity” exists on the inside. They enter through one of the “poles” at the center axis, descent on long ladders and staircases, and explore what seem to be “towns” and fields. There is a cylindrical “sea” dividing one half of Rama from the other. At the far end are huge spikes jutting out parallel to the axis. They discover alien robots who try to clean up after them, but no intelligent life. One astronauts uses a light aerocycle to sail through the air down the axis to reach the other side, just as a huge storm erupts, an effect of the warming of Rama and its insides as it approaches the sun. And much more fascinating stuff.

Some particular notes:

- A key early observation the human explorers make is that the Ramans (the presumed aliens who built the craft) build in triple-redundancy, two backups of every major component. This theme provides the one big surprise, at end, when we realize the story we’ve been told isn’t really over. (This is an example of a so-called slingshot ending, per SFE https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/slingshot_ending.)

- Several sequels did appear, but they were written by Gentry Lee, with Clarke’s guidance; and Lee’s style was as turgid as Clarke’s was lucid and succinct. I tried the first of them, but never finished any of them.

- The novel is constructed of many short chapters (as were all of Clarke’s subsequent novels), some of them describing background details of life on Earth and in the colonized other planets. In fact it resembles a bit those old utopian novels that were basically tours of their world without much actual plot.

- One such detail concerns sexual relations. One is about how Endeavour’s captain has one wife on Earth and another on Mars, who know each other and are friendly. Another is about a crewman who has an “inseparable” male companion in a “stable liaison,” even as they both share a wife back on Earth.

- (I’ve long noticed that Clarke, who was gay but closeted until much later, began including, with this book, characters who were close companions without spelling out their homosexual relationship. He gets a bit more frank in later novels.)

- And another is about a crewman who a member of the Fifth Church of Christ, Cosmonaut, a church that believes Jesus was a visitor from space, and that Rama is some kind of Ark come to save humanity.

- Bottom line: this is a book about how alien technology might reveals how other intelligences have assumptions about reality that we do not share, and cannot understand. And that it’s *thrilling* to discover such things. And, implicitly, how humans have a kind of “faith” that, should we ever meet alien intelligences, we will find they really have discovered knowledge and powers inconceivable to our science.