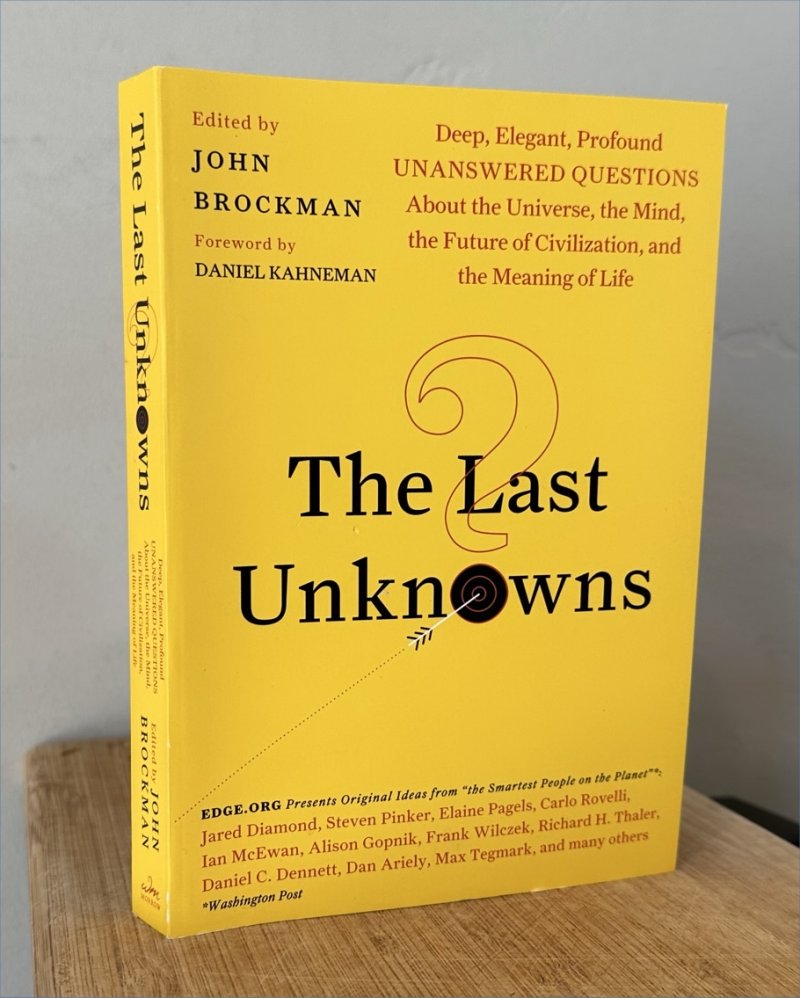

This is a sequel to a post I did back in March, Last Questions and Possible Answers, 1, in which I considered the John Brockman book The Last Unknowns, in which he gathers deep unanswered questions about “the universe, the mind, the future of civilization, and the meaning of life” from numerous scientists and philosophers and other of the “smartest people on the planet.”

Out of the perhaps 250 contributors to this 325 page book, in that earlier post I addressed 19 contributors from the first 100 pages or so. Today I’m covering 13 more contributors from the next 70 pages. I’ve also refined and polished that earlier post. And obviously I have a couple more posts to go, to get through the whole book, even selectively.

Again, I’m quoting their questions and giving my own take on the nature of possible answers, based on my reading and thoughts over many years.

Jonathan Gottschall, p107: Are stories bad for us?

Gottschall has written books about the power of narratives. The answer is probably no, even though stories distract us from understanding the true nature of the universe, in which most things usually don’t happen for “reasons” as human conceive them, contrary to what many people like to think. In fact stories are likely beneficial because the power of narrative provides human with ways of thinking about the world that promote survival, if not the understanding of reality.

A.C. Grayling, p111: What ethical responsibilities will humans owe to AGI systems?

Where AGI is “artificial general intelligence.” Not much, if the current chatbots are the best AI can do; but if AI were truly intelligent, or sentient, then they would deserve ethical considerations equivalent to those for humans. Still, Grayling might mean something more than current “AI” in his term AGI.

Jonathan Haidt, p114: Why is it so hard to find the truth?

Depends on what is meant by truth, surely; too vague a question. But since Haidt’s concerns are psychological, in the modern sense, he is probably pondering the range of human natures and how different people perceive the world so differently. On that point, there will probably never be a universal truth that everyone will agree on, not even 2 + 2 = 4. (Recall Orwell’s totalitarian example of 2 + 2 = 5. And the example of a certain believer who if the Bible said that, he’d accept it. You can find it on YouTube.)

Sam Harris, p120-1: Is the actual all that is possible?

Not in the sense that we can imagine mathematical spaces that don’t seem to exist in reality. They’re real, or possible, in some sense, even if they’re not actual. David Deutsch wrestles with questions like this as he finds analogies between the big theories. This is more of a semantic question.

Bruce Hood, P130: What would the mind of a child raised in total isolation of other animals be like?

Probably inhuman compared to anything we’re familiar with. It’s well established that children need interaction with their mother (or other parent), then other adults, later children like themselves, and so on, to socially develop. At the same time a certain base human nature has evolved over millennia, what you might call instincts or intuitions, and the isolated child would still have those; the mind is not a blank slate.

Nicholas Humphrey, p134: Why is the world so beautiful?

Humphrey has written several books about the mind and consciousness; my favorite is this one. Interesting question! Is the world beautiful? What is beauty? Why isn’t everything in the world beautiful? The credulous like to point to beautiful sunsets as evidence of God, but, I’ve always thought, if God created everything, then everything in the world should be as much signs of the creator as anything else, from beautiful sunsets to piles of manure in the road. If humans sense that some things are beautiful (and other things are not), then something else is going on (in the human mind) than the perception of some supernatural goodness.

The fallback answer, in the context of everything actually known about the human mind and its evolution, is that for some utilitarian reason, the human mind has evolved to perceive some things, more than other things, as ‘beautiful,’ because doing so promotes behavior that leads to greater reproductive success than would be true without such perceptions. Sounds clinical, but that’s how it works. It’s the subtleties of how it works that makes it such a profound question.

Matthew O. Jackson, p138-9: Will humanity end up with one culture?

Yes and no. Humanity already has one culture in the sense of having settled on common protocols for communication, banking, travel — and calendar. And the more we communicate and travel, the more local differences in culture will blend together, to the consternation of conservatives everywhere. The world a century from now (assuming we don’t exterminate ourselves somehow) will be more homogeneous that it is today. That said, there will *always* be local variations in culture. Each generation creates its own culture! To distinguish themselves from the previous generation. There’s always new slang, new music, new fashion, even new religions, whenever people want to distinguish themselves from everyone else, and feel special. This will never go away.

Gordon Kane, p144: Are the laws of physics unique and inevitable?

We don’t know. There’s lots of speculation about the “multiverse” and how other entire cosmoses might exist with *different* laws of physics. And lots of insight into how the laws of physics in *our* universe *seem* so craftily aligned that were any of the particles or forces be just a little bit different, life would be impossible. Which leads to the reverse observation that, since life does exist in our universe, those fundamental forces *have* to be what they are, or we would not be here to ask the question. This leads to a sort of evolutionary perspective on potential the generation of sub-universes, perhaps through black holes or mere quantum fluctuations; there may be an infinite number of universes, with only a few, or maybe only one (we have no way of even speculating), amenable to life. On the other hand, maybe all possible combinations of varying fundamental forces are unable to exist. Some have speculated that our universe is the way it is because no other combination of fundamental forces ‘works.’ We may never know.

Stuart A. Kauffman, p145: What is consciousness?

This indeed is a fundamental unknown. There’s a sense of self-awareness that humans like to attribute to themselves as being both special among all forms of life, and somehow incomprehensible. Lots of philosophers have written lots of books exploring potential ‘solutions’ to this ‘problem,’ while a few wonder if it’s really such a problem at all.

Slightly aside, as I’ve not mentioned before. The recent concerns over AI chatbots, which seem sorta smart in sophomoric ways, but which really are a kind of plagiarism and recombination of everything that’s out there on the web, makes me wonder about real people. How many real people are ‘conscious’ or ‘creative’ rather than simply, like the chatbots, merely processing inputs from the day before and generating rote variations to those in order to live the next? How many *humans* are ‘intelligent’ in the ways we worry AIs might become? Perhaps not very many.

Brian G. Keating, p146-7: Is there any observational evidence that could shake your faith, or lack thereof?

This isn’t so much a fundamental mystery, as an heuristic for how to approach life, a question everyone should ask themselves if they are intellectually honest, and conscious in the sense of the the previous question. If nothing would shake your faith, then are you a conscious, rational human being? Or a rote plagiarist of all the previous days of your lives? If you can never change, as circumstances or evidence change, then in what sense are you alive?

Kevin Kelly, p149: How can the process of science be improved?

Interesting question, perhaps inspired by questions in recent years about the peer review process, the difficulties in getting published in academic journals, and so on, including of course the inescapable fact that scientists are people too, and subject to the same psychological biases and petty emotions that everyone else is. But without needing to offer specifics, the answer to the question is: the process of science will itself improve the process of science. There’s no other way it could happen. No politicians, say, are going to come in with dictates about how to improve the process of science. Given human nature, refinements of the process may take time — there’s the old saw about how advances in science sometimes need to wait for the older generation to die off — but the process itself is attuned to improving itself. (I’m also reminded of the Asimov quip about rationalism: if you have a valid argument as to why rationalism is not the best way to draw conclusions about the world, then you are being a rationalist.)

Kai Krause, p156: What will happen to religion on Earth when the first alien life form is found?

Mmm, I would say, the religions will adapt, as they’ve always done, and reinterpret their scriptures, as they’ve always done, to take into account new evidence about the world. Just as they’ve done, albeit reluctantly, over the past few centuries with scientific discoveries about worlds beyond Earth and the nature of life. At the same time, there will always be holdouts, who insist that the ancient holy books are inerrant, and any evidence to the contrary is fraudulent, or a conspiracy by those who have rejected God. That is, human nature will not change.

Seth Lloyd, p171: How did our complex universe arise out of simple physical laws?

I suspect this is a question that Lloyd, who’s written books like this one, already has a good take on. The answer is that complexity easily arises out of simple principles, in ways that confound human intuition. A principle example is the early computer simulation, called Conway’s Game of Life, that shows how simple rules, for how a grid of squares should change color based on the colors of adjacent squares, develop remarkably complex patterns of objects that moved about as if… alive. Other examples include, for instance, how our entire complex universe is made up of only 100 or so distinct atoms. Or how all the books in the world, even the Bible, are composed of only 26 letters, in the English language. Complexity is not a mystery that has to be solved by “God”.