This week’s novella covered by the Facebook Group reading Gardner Dozois’s big anthology first discussed here is “Mr. Boy,” by James Patrick Kelly, first published in the June 1990 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction.

Kelly is a versatile writer who, like Walter Jon Williams at short fiction length, rarely writes the same kind of story twice. (Unlike WJW, JPK has published relatively few novels.) Still, it’s possible to characterize JPK’s writing to some extent: by the late 1980s he was grouped with a few other writers, including John Kessel and Kim Stanley Robinson, as being of the “humanist” branch of SF, in contrast to the “cyberpunks” headed by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, who were making the most noise and getting the most attention in SF in that era. (WJW wrote a cyberpunk novel or two.)

Curiously, then, “Mr. Boy” might be read as JPK’s dip into cyberpunk, or more correctly a consideration and rejection of it.

The narrator of “Mr. Boy” is Peter Cage, referred to as “Mr. Boy” since he has been repeatedly “stunted,” his genes “twanked,” so that he will remain 12-years-old indefinitely. His mom, who keeps paying for the rejuvenations, has reconfigured herself via similar technology into a 3/4 scale replica of the Statue of Liberty, sitting forever on a lot along Route 123 and attended to by various “remotes,” servants playing various roles.

Mr. Boy lives in a virtual world, in which his friends can reconfigure themselves as dinosaurs or teddy bears, and where they can all party in Virtual Environments accessible through the local net while they wear joysuits. After some preliminaries the story kicks off at such a party, held in a simulation of the White House, in which a snowman confronts Mr. Boy about a stolen information, in particular a photograph of a dead CEO. We already know that Mr. Boy has, in fact, acquired this photo; it has some weird pseudo-pornographic appeal to him.

Further, something is changing–maybe his last rejuv didn’t quite work. Mr. Boy has noticed a girl. The girl shows up at the party, admitting she’s just moved here from Indiana. He shows her around and explains the scene. And he meets her family, parents and brother, who run a plant shop built over Amtrak rails, leading a very different way of life than him and his friends. He gets a good talking to from her father.

And the government agent keeps threatening him about the corpse photo. And then he learns his mother isn’t really there in her Statue of Liberty as he’s always believed.

(Mild spoiler.) And so Mr. Boy, already increasingly irritable and uncooperative, reacts, and rebels. One set of values for another. From static and virtual and rich, to poor and happy and in love; from irresponsibility, to living in the real world. Cyberpunk to humanist, perhaps.

\

Still, it’s a busy story, almost overwhelmed by the foreground setting, with numerous characters to keep track of in their various guises, and the requisite futuristic lingo (in addition to terms already mentioned: “cush,” “Carefree,” “smash party”) to learn by context. (A “smash party,” it turns out, involves a contest to smash a 200-year-old piano into parts small enough to fit through a certain-sized hole, quickly enough to break last year’s record of three some minutes. –While in last week’s story Joe Haldeman explained how to literally eat a grand piano, even though it would take 300 years!) But this kind of fiction, the disorientation of being dropped, unbriefed, into a future world, is for many one of the pleasures of science fiction.

\\

Kelly was (is, though he’s slowing down a little) a prolific short fiction writer, and for years he managed to publish a story in each June issue of Asimov’s Magazine. Those stories began with “The Cruelest Month” in 1983, went on with others including “Saint Theresa of the Aliens” and “Solstice” and “Rat” in the ’80s, then “Mr. Boy” in 1990, and over the following decade plus some of his best-known stories. Which I happened to review in Locus Magazine at the time. So here I will reproduce my reviews of five of those later stories, as submitted. I have not reread these lately! And if I were to I might well refine my takes.

\\

June 1995:

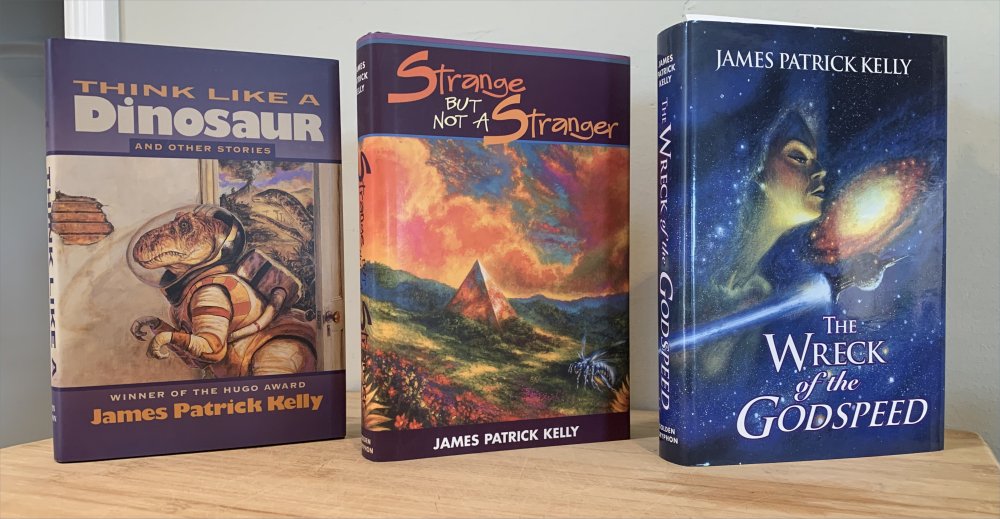

The cover story is James Patrick Kelly’s “Think Like a Dinosaur”, which revisits a classic sf conundrum, one ignored by superficial hardcore sf, the problem of what it means to use a teleportation device (like Star Trek’s transporter). Alien “dinos” have brought humanity much high technology, but not permission to break out into the galaxy, considering humanity an immature “baby” race. Michael Burr is a student of the aliens, eager to help humanity measure up, who’s doubling as a guide at a lunar “migration” station which, courtesy dino technology, enables human tourists to be scanned and sent across the light years to other planets. He helps one such tourist overcome her qualms as she realizes that, though a duplicate of herself will be created out on Epsilon Leo 4, the she that remains will be — destroyed. Dinos consider such qualms evidence that humans aren’t fit to deal with the real world. Burr’s resolution of the situation cleverly resembles a minor time travel paradox, but has a visceral impact nearly the equal of the ending Budrys’ classic Rogue Moon, though on a quite different emotional note.

\

June 1997:

James Patrick Kelly’s “Itsy Bitsy Spider”, in contrast, is a near-future character story about a middle-aged woman who seeks out her father after 20 years. She finds him in a retirement community, where she’s greeted at the door by a little girl, or rather a bot playing the role of herself as a little girl, complete with her own dolls and toys. Her father is senile, unaware of who this adult woman is in his house. There are no surprises or profound morals here, just a touching, subtle story of a way in which technology might allow the indulgence of avoiding the complications of real-life relationships.

\

June 1998:

“Lovestory” is an alien viewpoint story concerning a race with just two sexes but three roles in rearing offspring. Two of the roles are female, the mother, who bears the child, and the “Mam,” who nurtures it in a pouch and then raises it through childhood. The third is the male, the father. The story concerns a family in which the mother, Valun, has deserted the father Silmien and their Mam Totta. In fact, Valun has run off to live with the aliens, who are obviously visiting human beings. Mam is upset because the family’s child or “scrap” hasn’t yet been given a name, and moreover the mother is due with another baby soon. Silmien assures Mam it wasn’t her fault, and performs the naming duty himself. He attends the child Tevul (now a “tween” rather than a scrap) to the community garden where she will meet others her age and eventually find mates of her own.

And then Valun returns to the family, about to give birth to her second child and eager to explain what drew her to the humans. It’s their medicine; humans control their bodies, and they’ve taught her that there’s nothing inevitable about her own race’s biology—not its laws of birth order, or their short lifespans, or even families at all. Everything can be decided; reality is a decision.

Kelly invents an alien race that is similar enough to humanity to invite emotional appeal yet different enough to be provocative. The names of roles are suggestive of English terms; “Mam” is like mother, and “tween” is like between or teenager. The tripartite parenting roles are persuasively plausible, even reasonable. The mother and father’s roles are more in parity than they are among humans, while the Mam, who interacts with the growing child, is the emotional and sentimental one.

There’s also an interesting counter theme in the idea of “stories” by which this race thinks about the world. Mam reads “lovestories” that are the equivalent of our romance novels, while father writes other kinds of stories by profession, and Tevul writes a “lifestory” as an academic assignment. Mam’s concern about Valun’s motives amount to what kind of story her return to the family will make. It is, indeed, a love story: Valun exhibits genuine concern for her family’s well being, and the family’s reunification provides an emotional resolution. In its appeal to alien exoticism and its emotional power, Kelly’s story invites comparison to such SF classics as Tiptree’s “Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death” and Octavia Butler’s “Bloodchild”.

\

June 1999:

This year’s June Asimov’s story by James Patrick Kelly is “1016 to 1”, in which Ray Beaumont is 6th grade science fiction reader in 1962 who one day meets an invisible man. Ray is savvy enough from his reading to recognize clues that the man, Cross, is a time traveler from the future. Ray hides Cross in the family bomb shelter and agrees to help purchase a list of supplies Cross needs for his trip into New York City on October 26th. Meanwhile President Kennedy makes a speech on TV that alarms Ray’s mother into thinking World War III is about to begin. When his plans go awry, Cross urges Ray to make the trip into the city for him, even though, Cross allows, Ray’s chances of success are only 1016 to 1. At stake is nuclear war the future of life on earth.

The story powerfully evokes times that many readers are apt to identify with on several levels. It is the era of the Cold War when it seemed as if the world could end at any moment; it is the era of personal discovery by an outcast kid finding refuge and excitement in the worlds of science fiction; and it’s a time of life when kids often make unsettling discoveries about their parents’ shortcomings. But the story isn’t just an exercise in nostalgia. By suggesting a couple different ways in which history might go, Kelly plausibly revives the threat of atomic doom that no one, including SF writers, pays much attention to any more. The nuclear arsenals still mostly exist, Kelly points out, and just because the world didn’t end when everyone was afraid it might, doesn’t mean it still can’t.

\

June 2001:

The cover story of this issue is James Patrick Kelly’s “Undone” (the latest in a string of June-published Asimov’s stories going on 20 years now), and it’s the most science-fictiony story you’re likely to read in a while; the author explicitly credits Cordwainer Smith and Alfred Bester as inspirations. The story opens as Mada flees space-going assailants by hastily jumping upwhen through time, trailed by an identity mine placed five minutes in her past. With the help of her Dependent Intelligence ship’s AI she discovers she’s jumped two-tenths of a galactic spin—20 million years—into the future. Her own planet Trueborn now empty of people, she finds Earth occupied by a bucolic colony living “a never-ending vacation”. Dressing the part, she lands and enters a village, eating at a restaurant and chatting with Owen the waiter. As any tourist might, she experiences awkward miscommunications typical in an unfamiliar culture.

But Mada can travel through time! So she “undoes” awkward moments by instructing her ship to skip downwhen two minutes, or four minutes—but never more than five, the trigger of that identity mine that would wipe out her existence. Kelly depicts such skips with a typographical gimmick worthy of Alfred Bester; he splits the page in two columns, the left being a word-by-word reversal of the previous half page or so (in tiny type), while carrying on in the right column before resuming the story at a moment in the past. While the effect of these corrections are trivial at first, they gain increasing importance as Mada steals Owen away to another planet to start a fresh human colony in order to preserve her culture and its legacy of Three Universal Rights, which include free access to the timelines. How can she do this without destroying herself?

The story varies in tone and pace as Mada moves from planet to planet, but the effect of the apparently mismatched scenes is, one, to give Kelly material to pull off a clever ending that solves Mada’s immediate problem while bringing together the story’s other themes (rights, intelligence), and two, it suggests a universe that is larger and more complex than the small amount shown in the story—just as Cordwainer Smith’s stories did. The free-wheeling SFnal inventiveness of this story is indeed worthy of Bester and Smith.

\\

You can see how the reviews got longer. IIRC my favorites of all of these were “Lovestory” and “Undone.” And someday I’ll read them again.